Inflation Hurts Everyone, But So Does Unemployment

Research shows that the pain of unemployment is generalized, not localized. And that it's even more painful than inflation.

Last week, I joined David Westin on Bloomberg TV to talk about what the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) are doing to try to tame inflation. If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, then you know that I don’t subscribe to the conventional view that a series of aggressive and indiscriminate rate hikes is the right way to respond to our current bout of high inflation. Indeed, I’ve called it Bad Medicine. It comes with some nasty side effects, and there’s no guarantee it will cure the disease. Moreover, if rate hikes result in less capacity building (lower future supply), trillions of dollars in future interest income going to bondholders (higher future demand), and higher operating costs for firms that rely on debt-financing (which can get passed on to consumers), inflation could even get worse.

But we are where we are. The Fed is committed to raising interest rates until it sees “clear and convincing” evidence that inflation is coming down. As Chair Powell put it in a recent speech, it’s time for Americans to brace for some pain.1

Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses.

How much pain?

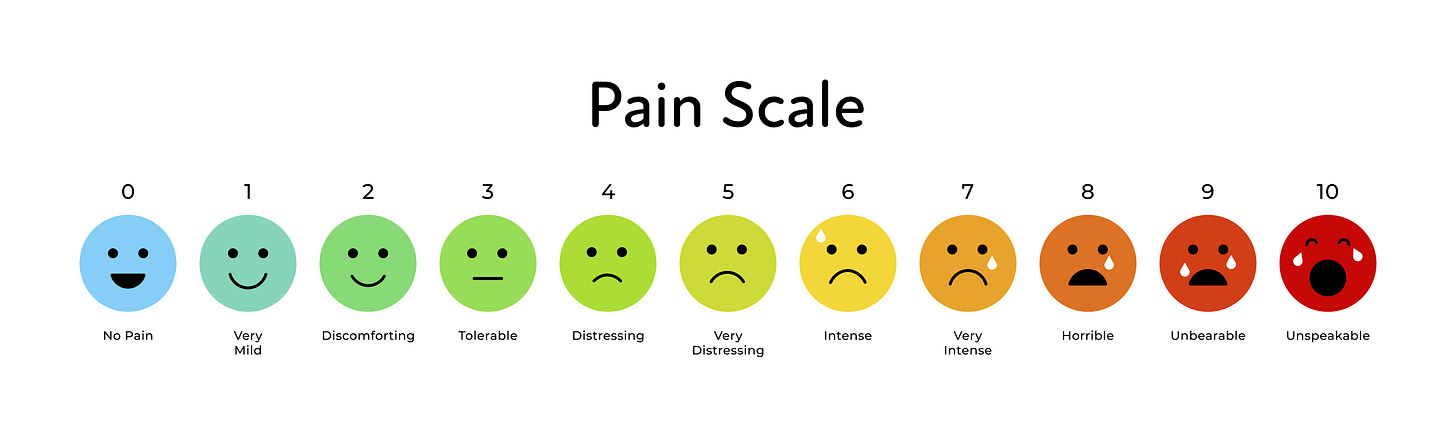

Stubbed your toe pain? Dislocated your shoulder pain? Giving birth without an epidural pain?

When Powell talks about the Federal Reserve using interest rates to engineer a period of “below trend growth” and “softening of labor market conditions” until it brings “some pain,” he’s describing an economic slowdown that’s sharp enough to drive the unemployment rate higher.

How much higher?

Of course no one at the Fed will actually come right out and say that their strategy for bringing down inflation is to drive people out of work. That would be uncouth. But Wall Street investors know how to parse Fedspeak:

David Rubenstein, the billionaire investor and co-founder of The Carlyle Group (CG), told CNN last week the Fed is actively rooting for the unemployment rate to go up to get inflation under control.

“He can’t quite say this, but if the unemployment rate goes up to 4% or 5% or 6%, inflation will [probably] be tamed a bit,” Rubenstein said of Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, whom he hired a quarter-century ago to work in private equity. “But he can’t come out and say, ‘I hope the unemployment rate goes up to 6%.’ That doesn’t sound politically very attractive to say that.”

While Fed officials are reluctant to draw a lot of attention2 to how high the unemployment rate might “need” to go in order to get inflation back down to 2%, the accounting and consulting firm RSM has estimated that it could involve the loss of 5.3 million jobs, which would drive unemployment up to a whopping 6.7 percent.

You might expect economists to be vocally pushing back against this sort of thing. After all, embracing policies that are designed to throw millions of people out of work seems both cruel and inefficient. Isn’t economics supposed to help us make efficient use of our resources?

While there are certainly economists (including some former Fed economists) who oppose the notion that we must add to unemployment in order to subtract from inflation, the profession as a whole simply thinks of it as a necessary tradeoff. To get more of something good (price stability), you have to endure more of something bad (unemployment). No pain, no gain!

Puuusshhh!

Many influential economists rely on this sort of crude Phillips Curve thinking. Just last week, the Brookings Institution published a paper that concluded that much higher unemployment will probably be necessary in order to bring inflation back down to 2%. In response, Jason Furman, who chaired the Council of Economic Advisors under President Obama, leaned into the paper’s findings and ratcheted up the pain scale:

In an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal this week that, based on Brookings' findings, the Fed will need to be aggressive about raising rates even if unemployment continues to rise. Running his own calculations, Furman says that the US would need an average unemployment rate of about 6.5% in 2023 and 2024 to hit its 2% inflation rate target.

If things unfold as Furman projects—and he cautions that the outlook “could be more painful”—then we could see a near doubling of unemployment over the next two years. Instead of the 3.7% unemployment rate the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in August, we might see 7% or 8% next year or the year after. People have different thresholds for pain, but I would position a rise in joblessness of that magnitude somewhere to the right of Very Intense (7).

Nevertheless, Furman’s advice is for the Fed to simply push through it. “Fighting inflation should be the central bank's only focus.” Look away as millions of new job entrants and current job seekers get locked out of employment. Do not waver as millions of people who are currently working and supporting their families are thrown into unemployment. Hike and keep hiking until inflation is brought to heel. There is no more urgent economic task.

Unemployment is Painful, and Not Just for the Unemployed

There’s a tendency for people to think of inflation like the flu, where the pain is generalized. It hurts everywhere. With today’s inflation, pretty much everyone has to suffer the “pain at the pump” or feel the sting at the grocery store checkout. In contrast, many people think of unemployment as a sort of localized pain. Sure, it hurts the guy who gets laid off or the woman who struggles to find work but never manages to land a job, but as long as I don’t lose my job… (and I promise you that Jason Furman, Larry Summers, and the authors of that Brookings paper face a near zero probability of job loss as a result of a Fed-induced recession.)

This way of thinking about the relative pain associated with inflation versus unemployment helps to legitimize throwing 5 or 6 million (or more) people out of work for the sake of sparing hundreds of millions from higher-than-normal inflation. But it’s also wrong, because unemployment isn’t a localized pain. Not only does the pain of joblessness spill over onto broader society, but new research shows that the pain of inflation actually pales in comparison to the pain of unemployment.

Don’t believe me? Check out this piece by New York Times writer Peter Coy. Here’s an excerpt:

What’s worse, higher inflation or higher unemployment? That question is at the core of the debate over how rapidly the Federal Reserve should raise interest rates to cool off the economy and bring inflation down from its 40-year highs. If you think higher inflation is worse, then it makes sense to raise rates hard and fast, even at the cost of causing a recession. If you think higher unemployment is worse, then moving cautiously is a better choice.

The answer is actually pretty straightforward: Higher unemployment is worse than higher inflation if you go by the feelings of real people rather than the theories of economists.

A paper by three New Zealanders that’s forthcoming in the Journal of Money, Credit and Banking taps into results from the Gallup World Poll from 2005 to 2019, covering 1.5 million people in 141 nations. The poll includes questions about how people feel about their lives and their current situations. The researchers correlate how people answered those questions with economic conditions at the time in each country. (An earlier, slightly different version of the paper is available online.)

The findings are remarkable. People are nine to 13 times as likely to report sadness or physical pain in the short term when there’s been a one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate as when there’s been a one-percentage-point increase in the inflation rate. Similarly, an increase in unemployment is about six times as potent as an increase in inflation in lowering people’s self-assessments when they were asked a longer-term question about how they feel about their lives on a scale of zero to 10.

The beauty of the study is that it’s unbiased; the people answering the questions about their feelings had no idea that their answers would one day be used to assess the impact of inflation and unemployment on their lives. If they had been asked directly how they felt about inflation and unemployment, their answers might have been affected by what they had heard about those phenomena in the news or learned in school.

And speaking of what economists and central bankers learned in school, here’s what Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and economist Dean Baker wrote earlier today:

But these arguments are based on the standard Phillips curve models, and the fact is that inflation has parted ways with the Phillips curve (which assumes a straightforward inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment). After all, the large rise in inflation last year was not due to a sudden large drop in unemployment, and the recent slowdown in wage and price growth cannot be explained by high unemployment.

Given the latest data, it would be irresponsible for the Fed to create much higher unemployment deliberately, owing to a blind faith in the Phillips curve’s ongoing relevance. Policymaking is always conducted under conditions of uncertainty, and the uncertainties are especially large now. With inflation and inflationary expectations already dampening, the Fed should be assigning more weight to the downside risk of additional tightening: namely, that it would push an already battered US economy into recession. That should be enough reason for the Fed to take a break this month.

In other words, enough with the pain already.

And not just Americans. As I pointed out in my interview with David Westin last week, the Fed’s rate hikes also inflict pain on the rest of the world. This was also a central theme of my remarks at The European House—Ambrosetti forum in Italy a couple of weeks ago. Former Fed economist Claudia Sahm is also good to remind people that the Fed’s rate hikes inflict damage on countries that are heavily indebted in US dollars and those that rely on US dollars to purchase food, energy, and other vital imports.

The Federal Reserve does provide estimates of the expected path of inflation and unemployment, but officials tend to avoid drawing attention to the predicted rise in the national unemployment rate. Right now, the Fed expects that the unemployment rate will need to rise to 4.1% in 2024 in order to bring inflation back down to 2% by that time.

At some point, it's no longer a question of economists in high places doing bad science and making mistakes. It becomes clear it's a matter of political economy.

In political economy, we know that the political desires of anyone but wealthy people have no impact on what gets through Congress. But this same class of people and their Wall Street minions enjoy enormous soft power. (I'm sure you've noticed that it's difficult to get people to understand MMT when they are paid not to understand it, but it's even harder when they have unshakable prior ideological commitments to not understanding it, and when their friendships and professional status requires circling the wagon against outsiders in defense of orthodoxy)

In any case, soft power emanates from Wall Street through through public and specialist media to form an iron cage of orthodoxy inside which Powell comfortably lives.

It's unclear to me in a number of policy areas what to do when the people you're debating pretend to be engaging in an proper good-faith discourse, but their true opinions are as immovable as the Pope's commitment to the catechism.

Hi Stephanie. Your arguments here seem to me crystal clear. I’m an old man. I’ve been thru this before… serious inflation in the seventies, thousands thrown out of work, years of suffering until things got back to “normal.” Don’t economists have memories? Aren’t, say, the 70s “data?” Where does “unemployment compensation” come from, the guardian angel? This happens over and over. Why don’t economists…. Mmt folks excluded … live in the world? Oh, I see they live at Yale,

Harvard, at Stanford, et Al., and they aren’t unemployed. That explains it. Dan.