Biden Wants to Bring Down the Deficit. Powell Wants to Bring Down Inflation. Are Rate Hikes Undermining Both Goals?

Last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said, “the disinflationary process has begun.” Many breathed a sigh of relief even as Powell told us that the process of getting all the way back down to 2 percent would likely “take quite a bit of time.” To get inflation all the way back down to target, Powell told us to expect a series of ongoing increases in its benchmark interest rate.

This week, we learned that inflation continued to ease. I mean accelerate.

Headline inflation (CPI) for January showed that prices rose at their fastest month-over-month pace (0.5%) since October 2022. The data also showed that year-over-year inflation rose at its slowest pace (6.4%) since October 2021. You get a similarly mixed picture when you strip out food and energy and look at core inflation.

Before the January CPI report, the phrase “ongoing increases” was widely interpreted to mean a series of 25-basis point hikes, with the next one coming in March.1 But now there’s growing speculation that the Fed might go bigger in light of the fact that month-over-month inflation just accelerated.

Both Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester and St. Louis Fed President James Bullard are talking about a potential 50-basis point hike at next month’s meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). And while neither is currently a voting member of the committee, some have interpreted their statements as an indication that the mixed inflation report might cause the Fed to return to a more aggressive stance.

Regardless of what you expect Powell & Co. to do at the meeting, it’s clear that the Fed is determined to bring inflation back to its 2% target by continuing to raise interest rates “until the job done.”

The Fiscal Channel

But here’s the thing. At the macro level, the federal government is a net payer of interest,2 which means that the Fed’s rate hikes work like expansionary fiscal policy in the sense that they translate into hundreds of billions of dollars in additional spending by the federal government. Here’s how Warren Mosler explains it in his MMT White Paper:

MMT recognizes that a positive policy rate results in a payment of interest that can be understood as ‘basic income for those who already have money.’

MMT recognizes that with the government a net payer of interest, higher interest rates can impart an expansionary, inflationary (and regressive) bias through two types of channels -- interest income channels and forward pricing channels. This means that what’s called Fed ‘tightening’ by increasing rates may increase total spending and foster price increases, contrary to the advertised intended effects of reducing demand and bringing down inflation.

Likewise, lowering rates removes interest income from the economy which works to reduce demand and bring down inflation, again contrary to advertised intended effects.

What Mosler has been saying is that by pushing interest rates sharply higher, the Fed is keeping fiscal policy more expansionary than it would otherwise be. As a result, the government is putting a ton of extra cash into the hands of bondholders who may turn around and spend some of that windfall. And that additional spending can potentially sustain inflationary headwinds.

Obviously, rate hikes can also reduce borrowing and spending, especially on interest-sensitive items like housing and autos, and that can help tame inflationary pressures. Once you bring in expectations, exchange rate dynamics, private sector debt, etc…Well, as I’ve written many times before, there are even more cross currents to complicate the transmission mechanism.

The FOMC doesn’t have an interest rate dial that it can turn up by X percentage points in order to deliver a predetermined change in inflation. Movements in interest rates can ripple through the system in both semi-predictable and surprising ways.3

Mosler acknowledges that rate hikes create both winners (who have more to spend) and losers (who curtail spending). What matters is the balance of these opposing forces. And right now, he thinks the rate hikes are doing more to support aggregate demand than most people—especially central banks—realize.

We’ll look at some of the data in a moment. For now, let me just say that, while not discounting Mosler’s argument, I and other MMT economists have been more worried about the risk of recession as opposed to the risk of stickier inflation stemming from the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes. Here’s something I wrote last fall, and here’s a talk I gave last summer.

Meanwhile, it’s been almost a year since the Fed started its tightening cycle, and any objective view of the economy tells me that the rate hikes aren’t really working. If anything, inflation has moderated primarily because the factors that drove the lion’s share of the problem—i.e. pandemic-related supply-side disruptions—substantially abated in the second half of 2022.

So the Fed has stomped on the brakes in a historically aggressive way, and yet the rate hikes don’t seem to be delivering much traction.

Mosler isn’t surprised. He thinks the Fed (and other central banks) have the brake pedal and the gas pedal confused.

Let’s Look at Some Numbers

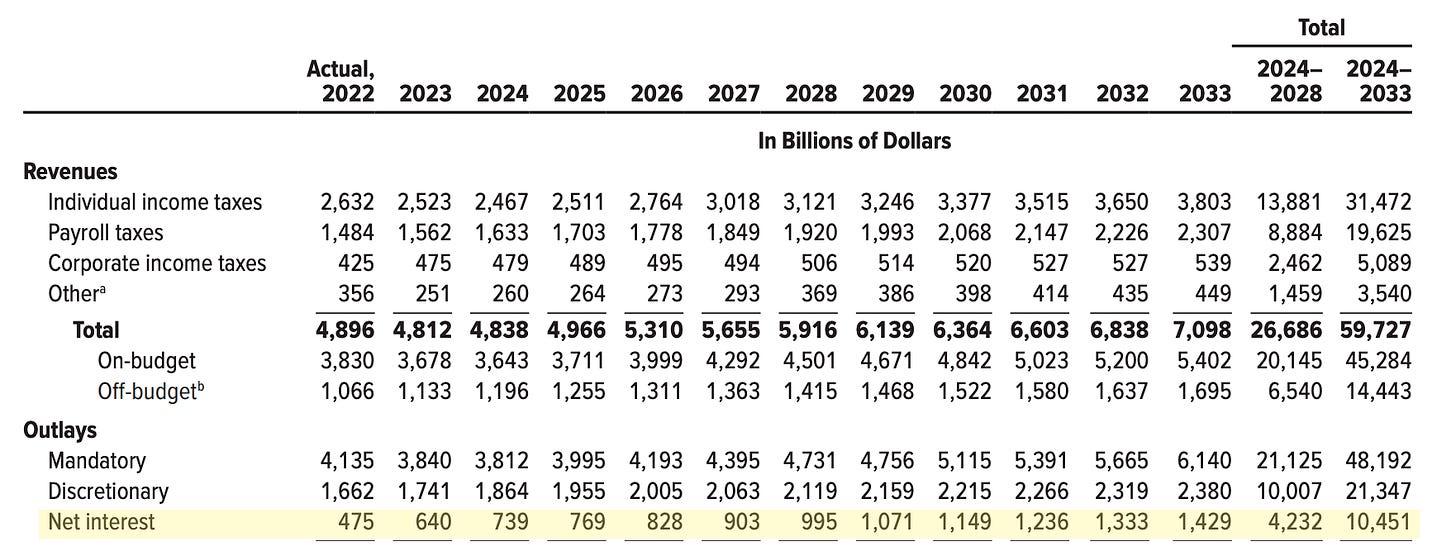

Mosler focuses on the fact that the federal government is a net payer of interest. If we look at the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest report, we get a sense of the impact the Fed’s rate hikes are projected to have on the amount of money the federal government will spend (and collect) in the coming years.

Let’s start by comparing what CBO is telling us now with what it was projecting back in May 2022, before the rate hikes really started in earnest.4

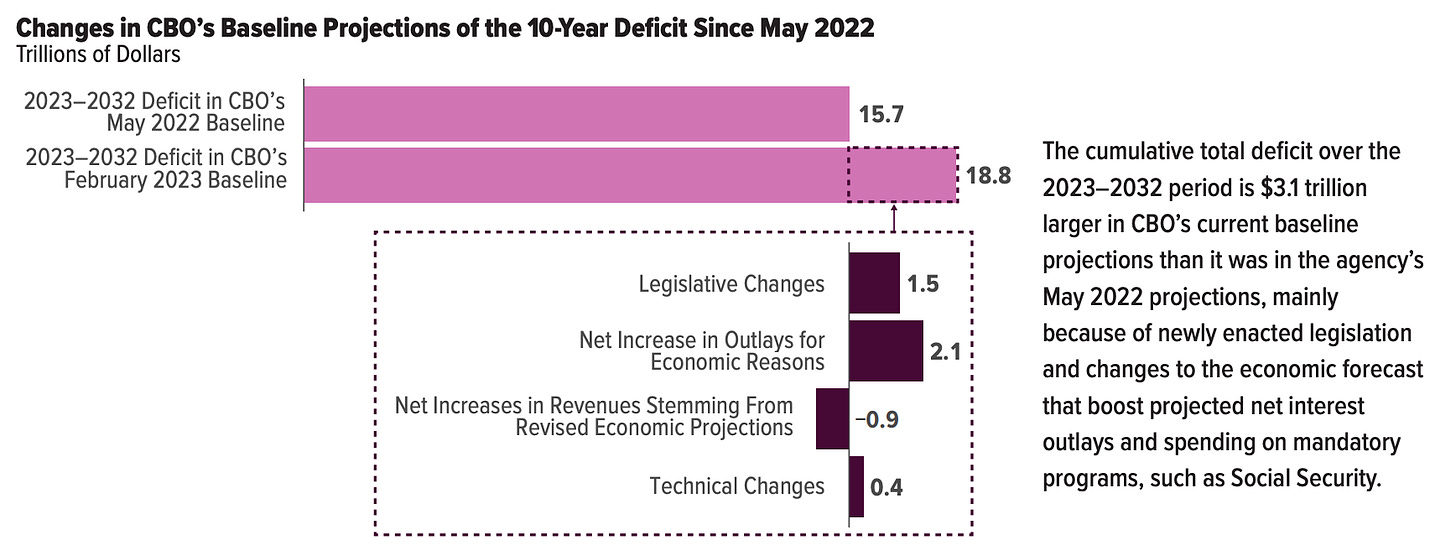

According to its latest estimates, CBO projects that the deficit for the current fiscal year (2023) will be $426 billion higher than previously anticipated (CBO’s May 2022 estimate was $1 trillion versus its February 2023 estimate of $1.4 trillion). Over the coming decade (2023-2032), CBO now expects cumulative deficits to come in $3.1 trillion higher than previously estimated.

That jump—and the projected rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio—is grabbing all the headlines, but let's stay focused on the income and budgetary impacts of the Fed’s rate hikes. Tighter monetary policy isn’t responsible for the entire increase in projected deficits, but it’s a major driver because the rate hikes substantially increase outlays while significantly reducing revenues.

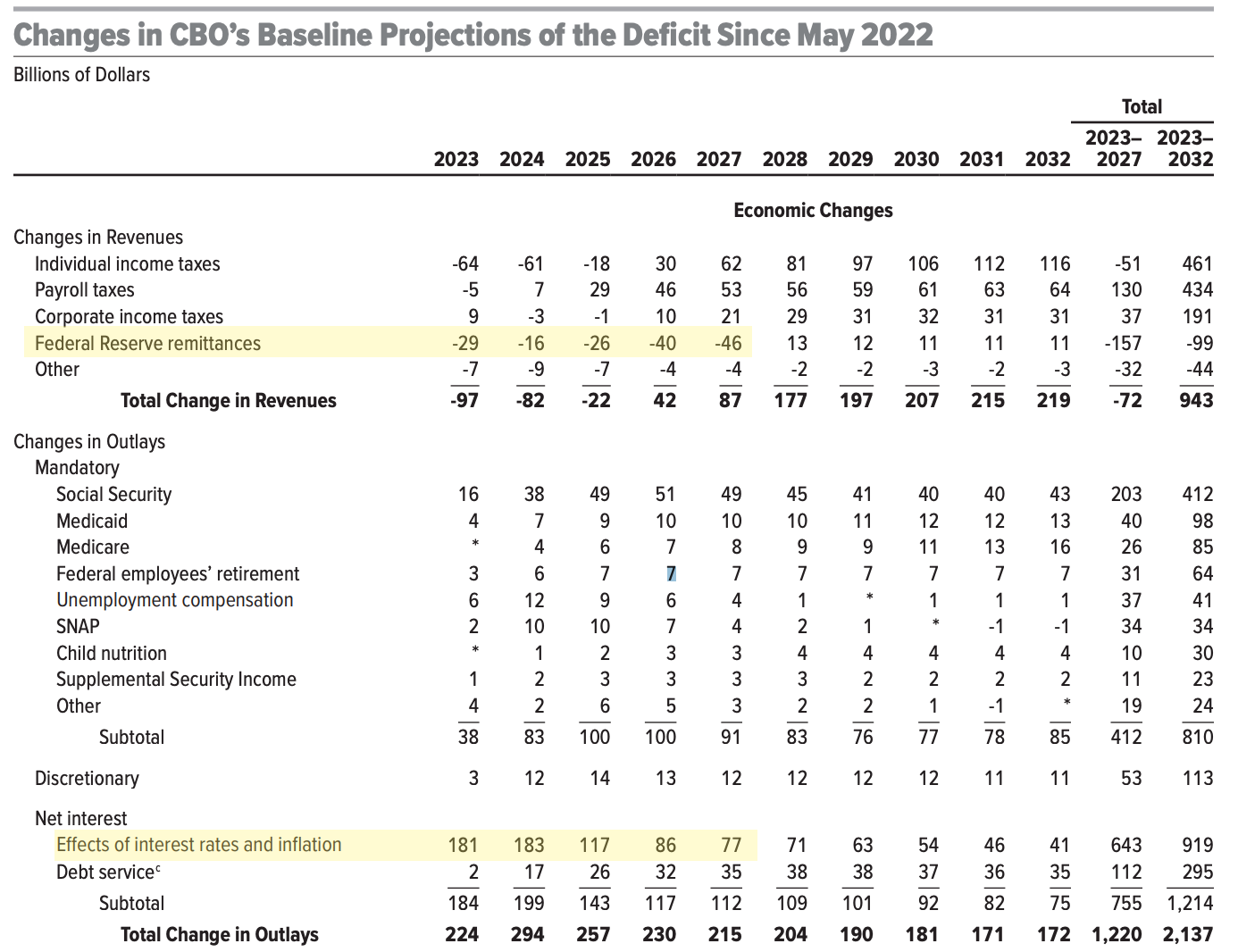

Compared with its May 2022 estimate, CBO now estimates that over the next 5 years, the federal government will pay out an additional $644 billion in net interest. This isn’t what will be paid out in total over that period. That’s a whopping $3.879 trillion! The $644 billion is the additional amount of net interest CBO thinks the government will end up spending over the next 5 years, mostly because of the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes.5

Now, the rate hikes don’t just hit the spending side of the government ledger. They impact the revenue side as well. That’s because rate hikes don’t just force the Treasury to hand out more interest income to bondholders, they cause the Federal Reserve to hand out more as well. That’s because the Fed pays interest on reserve balances (IORB). And the more interest the Federal Reserve pays to financial institutions with master accounts at the Fed, the less it remits to the Treasury each year. That means reduced revenues and increases in the deficit.

Looking again at the revisions to its May 2022 report, CBO now projects that over the next 5 years remittances from the Fed will be $157 billion lower than previously anticipated. Taken together, these two factors6 alone account for 40% of the projected increase in the deficit over the next 5 years. And half of the projected $426 billion increase in this year’s deficit.

And that doesn’t take into account some of the other ways the rate hikes end up causing the federal government to pay out more and take in less. Add in the indirect effects of the rate hikes—i.e. from a slowing economy—and the budgetary impacts of the Fed’s rate hikes get even bigger due to the automatic stabilizers.

As a reader of The Lens, you might be wondering, “Why do you care about the budgetary impacts? That seems inconsistent with MMT.” And you’re right! I’m not writing this because I’m interested in the fiscal impacts of the rate hikes, per se. I have concerns with the distributional implications of the rate hikes, and I’m always concerned with inflation risk.

So let’s close by returning to Mosler’s point about inflation.

In Closing

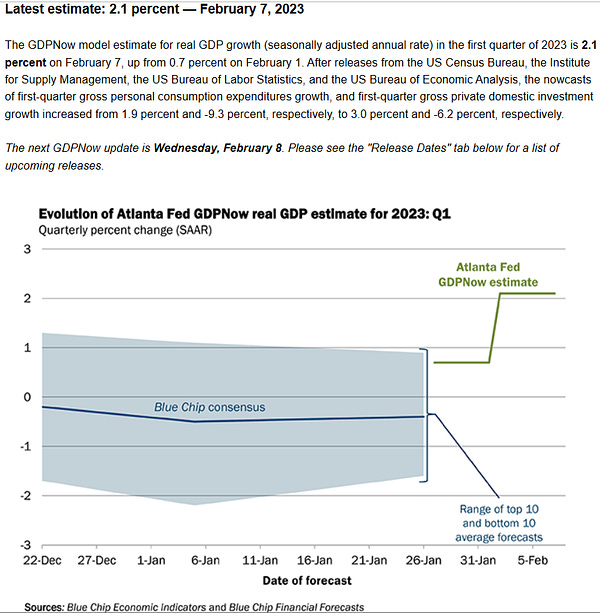

The Congressional Budget Office doesn’t allow for the possibility that higher interest rates might be supporting aggregate demand in the way Mosler imagines. For them, the Fed’s rate hikes only work as a brake pedal. The rate hikes are the reason CBO projects rising unemployment into 2024 and no economic growth this year.

Mosler wants us to at least consider the possibility that we might have this backwards. He’s saying that higher interest rates are a tailwind for some and a headwind for others. And, right now, he thinks they’re giving incomes enough of a lift to keep the economy chugging along with strong retail sales and the lowest unemployment rate in more than 50 years.

We’re not going to settle the matter here, but it’s worth thinking about. There’s a $31.4 trillion dollar Treasury market out there, and the Fed’s rate hikes obviously have a big impact on the amount of money that will go to paying interest to the holders of many of those securities.7 We're talking about a lot of interest income.8

Some of that interest will, as Mosler says, go to people who will spend some (or all) of what they receive. For others, the windfall will simply accumulate as savings. If a large share of the outstanding stock of government bonds is held by people with a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of interest income, then it’s easy to imagine a potent channel for the Fed’s rate hikes to feed inflationary pressures. If that’s not the case, then one might expect a more modest or even negligible inflationary impulse from higher rates. So it’s an empirical question. Here’s how the bonds are held.

When I have wrestled with this in the past, I thought about the size of the total bond market, how the bonds are held, and the maturity structure of those securities. And when I looked at the data across OECD countries, I found support for Mosler’s thesis.

I don’t know how strong the interest-income channel is or how much the Fed’s rate hikes might be contributing to aggregate demand and stickier inflation right now. What I do know is that Chair Powell wants to bring down inflation, and the rate hikes are adding substantially to the fiscal deficit.

I also know that President Biden would very much prefer to see the deficit moving in the opposite direction. For him, deficit reduction is a goal of his administration and something he’s encouraged the American people to keep an eye on as they evaluate his performance ahead of the next election.

Is it possible the rate hikes are undermining both goals?

Earlier this month, the Federal Reserve raised the federal funds rate (FFR) by 25-basis points, brining the target range for the FFR to between 4.50 and 4.75 percent.

As CBO explains, “In the budget, net outlays for interest consist of the government’s interest payments on federal debt, offset by interest income that the government receives. Net interest outlays are dominated by the interest paid to holders of the debt that the Treasury issues to the public. The Treasury also pays interest on debt issued to trust funds and other government accounts, but such payments are intragovernmental transactions that have no effect on the budget deficit.” The amount of net interest paid out each year is a function of both the outstanding stock of US Treasuries and the average interest rate on those securities.

Remember that a decade (or more) of near-zero (or lower) interest rates following the global financial crisis (2008/09) failed to spur rapid growth or accelerating inflation in the United States, across Europe, or in Japan.

The first rate hike (25-basis points) came in March 2022. The raised its target rate by 50-basis points in May.

Some of the added interest expense is due to other factors (like the passage of new legislation since May 2022), but the vast majority is due to Fed tightening.

$644B in increased outlays and $157B in reduced revenues.

The Fed’s rate hikes don’t automatically increase interest paid on non-marketable government bonds held by entities like Social Security. That is decided by Congress.

As CBO notes, the Treasury pays interest on securities held by the trust funds and other government accounts, but these “payments are intragovernmental transactions that have no effect on the budget deficit.”

This article and Mosler's point about rate hikes and how it's benefitting the rich via regressive stimulus is on point. There's nothing much to be said here other than to read this article and I would read it more than once. Important to understand that rate hike don't slow demand at all, but actually boost demand and add to deficit spending.

Excellent argument. The Fed is a one-trick pony; rate hikes are its only tool. It seems determined to use that tool whether it works or not!