Assume a Debt Crisis

How one bogus assumption drives the perception that America's debt is out of control.

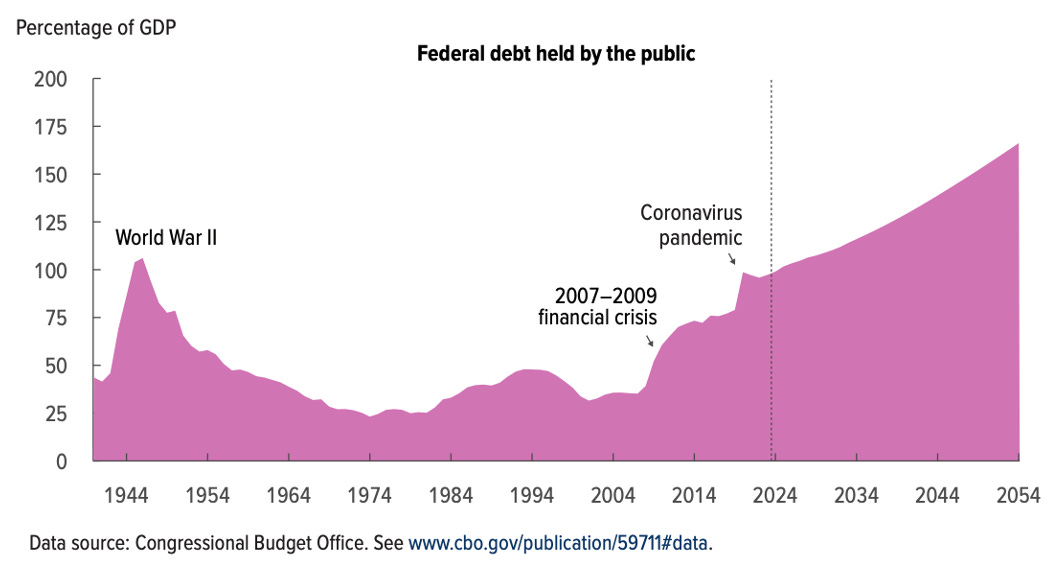

Yesterday, I wrote about the debt scolds who keep pointing to images like the one below as evidence of a looming debt problem. If you read through the Congressional Budget Office’s Long-Term Budget Outlook, you’ll get a sense of why they continue to paint a gloomy picture of America’s finances: a combination of too much spending and not enough revenue.

A casual observer might look at the chart and wonder, “Why would anyone expect the federal debt (as a share of GDP) to march steadily higher over the next 30 years? It looks nothing like what we experienced over the last 90 years.”

The Role of Assumptions

If you’re going to engage in an exercise like projecting the long-term debt ratio (and I don’t recommend it), then you’re going to have to make a lot of assumptions. That includes closing your eyes and assuming certain things won’t happen—e.g. wars, recessions, and pandemics. These things obviously do happen, and they clearly impact spending and revenue when they do, but they’re difficult (if not impossible) to see coming. So CBO assumes them away. The same goes for technological breakthroughs or other events that could bring a period of unexpectedly strong growth.1

In other words, the future path of debt/GDP will depend critically on what actually happens to the denominator. That’s why democrats and republicans often talk about “growing our way out of debt.” If you can engineer policies to really juice the denominator (GDP), the ratio will come down. “Problem” solved.2

But is there a problem to solve? I don’t believe there is. As I wrote yesterday:

Meanwhile, the so-called national debt remains nothing more than a historical record of US$ that have been spent by government and not taxed away from us over the centuries (i.e. part of our financial savings); the coveted r < g debt sustainability condition continues to hold; issuing Treasuries and paying interest remains a policy choice (not an economic imperative) so r < g can always be achieved by design; and the numbers used to generate CBO’s scary debt graph “are completely bogus.”

But it’s hard to overcome the perception of a debt problem when a picture is worth a thousand words. What almost no one seems to realize is that there’s a completely bogus assumption driving the entire image. Read that again.

I discovered this when I was working as the chief economist (for the democrats) on the U.S. Senate Budget Committee in 2015. We were preparing for a hearing, and I was e-mailing back-and-forth with Stephen Goss, who was the chief actuary of the Social Security Administration at the time. Lawmakers were obsessed with CBO’s long-term debt chart, but something about it just didn’t make sense.

When I finally hit on the right question, Goss replied: “Exactly!” I couldn’t believe what he went on to explain to me: CBO’s chart looked the way it did because of a totally bogus assumption.

I don’t recall CBO acknowledging this so explicitly back in 2015, but here’s a passage from their latest long-term budget report (my emphasis):

In accordance with statutory requirements, CBO’s projections reflect the assumptions that current laws generally remain unchanged, that some mandatory programs are extended after their authorizations lapse, and that spending on Medicare and Social Security continues as scheduled even if their trust funds are exhausted.

What Goss explained is that the most ubiquitous “proof” of a debt problem derives from an assumption that the government will violate the law. As I’ve explained countless times, the federal government has the financial ability to pay but not the legal authority to pay certain benefits once the trust funds associated with those programs are exhausted. Instead of doing what it has always done in the past—raise the payroll tax or make other adjustments—CBO assumes the government will borrow trillions of dollars and carry on paying promised benefits in full—something it does not have the authority to do under current law.

When I realized what was going on, I explained it to a friend, who decided to interview Goss and write the whole thing up for an article in The Nation. I tried to link to that article yesterday, but something went wrong and many of you wrote to tell me that the link was broken. Sorry about that! Here it is again. Let me quote from the article:

The numbers relied upon by [former Senate Budget Committe chair Mike] Enzi and far too many others inside the Beltway, including the Congressional Budget Office itself, are completely bogus. The methodology used by the CBO to create these projections exaggerates the federal government’s long-term debt projection by as much as 440 percent, creating a phony fiscal crisis where none exists.

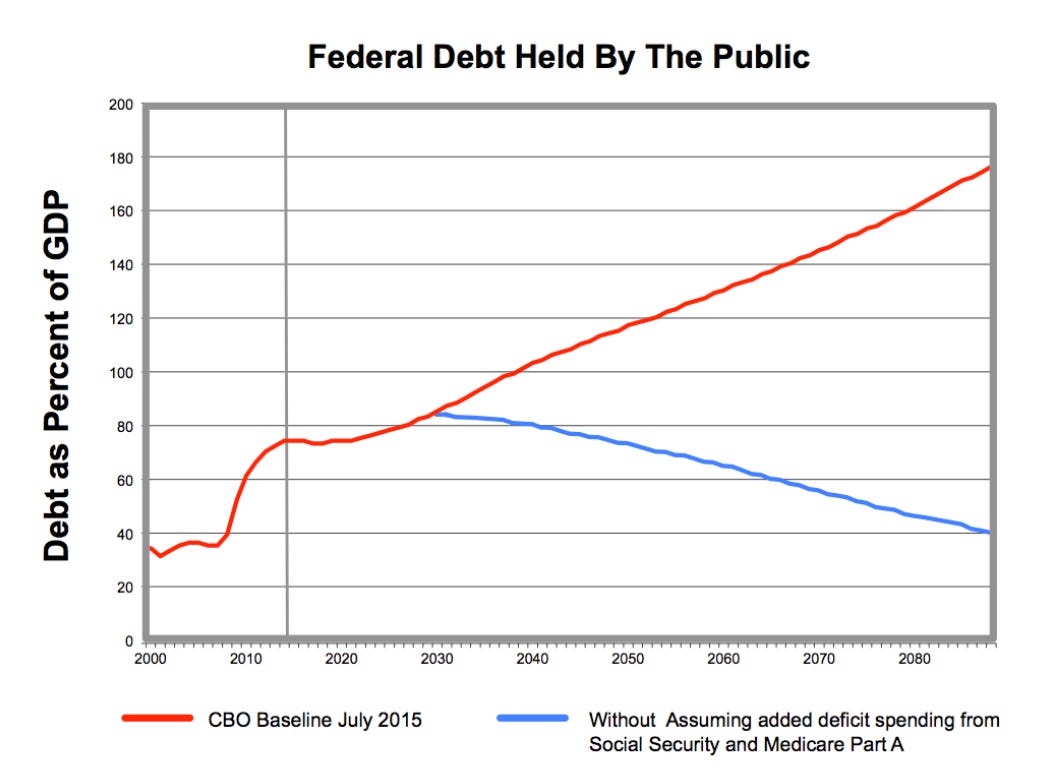

As it turned out, Goss had explained all of this to lawmakers. He shared a PowerPoint presentation that he created to show members of Congress what the picture would look like if CBO assumed that the government would follow the law (instead of violating it) if/when we reached the point of exhausting the trust funds. Here’s what he showed lawmakers.

Quoting from The Nation:

[The data] shows that starting in 2032 the federal government’s debt held by the public is on track to rapidly decline as a share of GDP, bottoming out at 40 percent. This is in stark contrast to the CBO’s sharply rising debt-to-GDP ratio, which peaks at 176 percent in 2090.

So there you have it. The entire “problem” derives from an assumption that the government will do something it isn’t allowed to do under current law.

Closing

If you adopt the MMT lens, then you’ll discover an array of other problems with CBO’s methodology, as Scott Fullwiler has shown. You’ll also understand why the U.S. wouldn’t face a debt crisis even under the debt path envisioned in CBO’s’ latest forecast. But the perception of an ever-rising debt ratio is cause for concern. It is easily weaponized to shape public opinion and justify gutting programs that millions of Americans rely on. We should acknowledge its deceptive underpinnings even as we work to advance a better understanding of the mechanics of public finance and the real limits on government spending.

None of that is unreasonable, however the exercise itself is not particularly valuable from an MMT perspective.

This is one reason that MMT—which rejects the very premise of a sovereign debt crisis— appeals to scholars who are concerned with the planetary/ecological implications of embracing policies aimed at “growing our way out of debt.”

OF COURSE the government wants to predict a scary crisis, in order to fool gullible taxpayers into agreeing that the programs that are targeted by the austerity-driven neoliberals are dangerous to the economy and have to be ended.

They never predict a scary crisis for the vastly bloated military expenditures.

As a casual student of MMT, I am familiar with the dictum that the federal government's deficit is the private sector's surplus. However, in the first graph in this email, it appears that the debt declined during the post-WW II years at the same time that there was broad-based prosperity, which would seem to conflict with that dictum. That prosperity continued until the early 1980s when the Reagan revolution kicked in, generating sharp increases in the national debt which continued until under the Clinton administration, when there was an actual federal surplus for a few years. GWB then introduced tax cuts while waging two wars and we also hit the 2007-2009 financial crisis and later still the pandemic, all of which saw huge annual deficits which continue today. But despite this prolonged period of high annual deficits, the middle class has not seen steadily rising inflation-adjusted incomes. I attribute this to those Reagan and Bush tax cuts and other policies that have funneled those private sector surpluses into the hands of the top 1%. Perhaps if we are to really make America great again, we need to return to the tax policies we had in the 1950's and 60's. But given the 1%'s ability to evade much of the tax on their incomes, I think we should replace the estate tax with a wealth tax instead.