A quick thought about yesterday’s inflation numbers. I saw the BLS report just as I was leaving the house to teach. According to the Labor Department, headline (CPI) inflation continued to ease, decelerating from a year-over-year rate of 8.5% in July to 8.3% in August. (As a reminder, we hit 9.1% in June, the highest inflation rate in four decades.) So yesterday’s report showed continued improvement in this closely-watched measure of inflation. Meanwhile, the month-over-month number came in tepid, rising at a modest (0.1%) compared to the prior month.

Food prices rose (0.8%) more slowly (disinflation) in August, and the energy index fell (-5.0%) for the second month in a row (deflation). It’s not that food is getting cheaper—it isn’t—but yesterday’s report notes that food prices showed “the smallest monthly increase in that index since December 2021.”

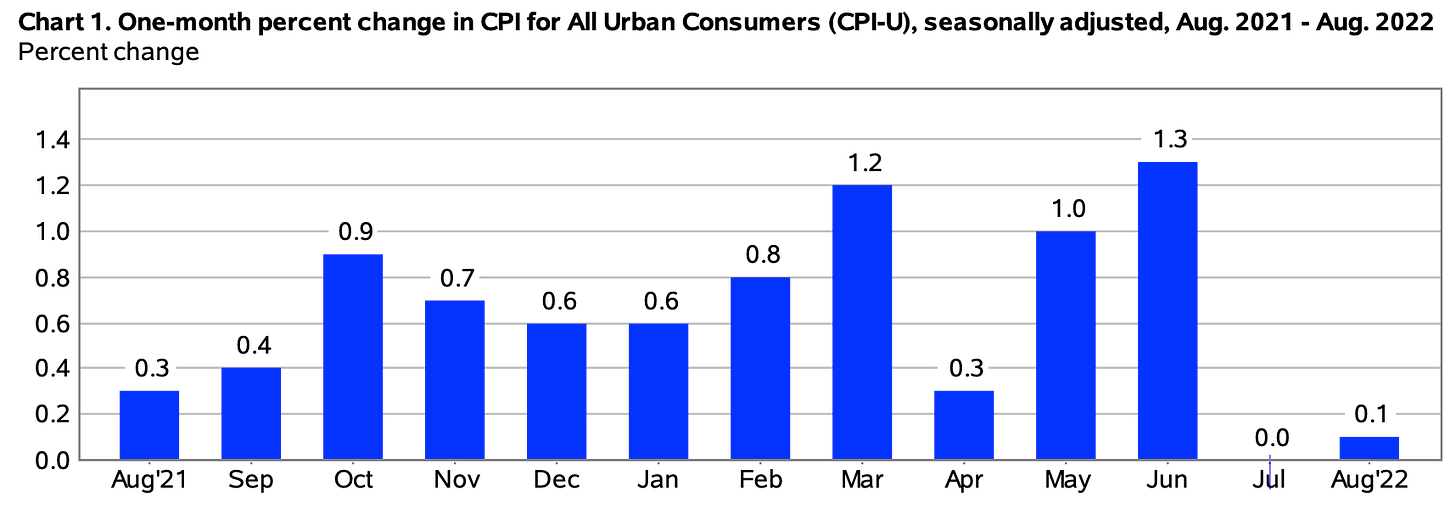

Here’s the chart—included in yesterday’s report—showing the monthly trend in overall consumer price inflation.

If that’s all there was to it, the ensuing market meltdown would make no sense. Of course, there was more to the story.

The CORE Problem

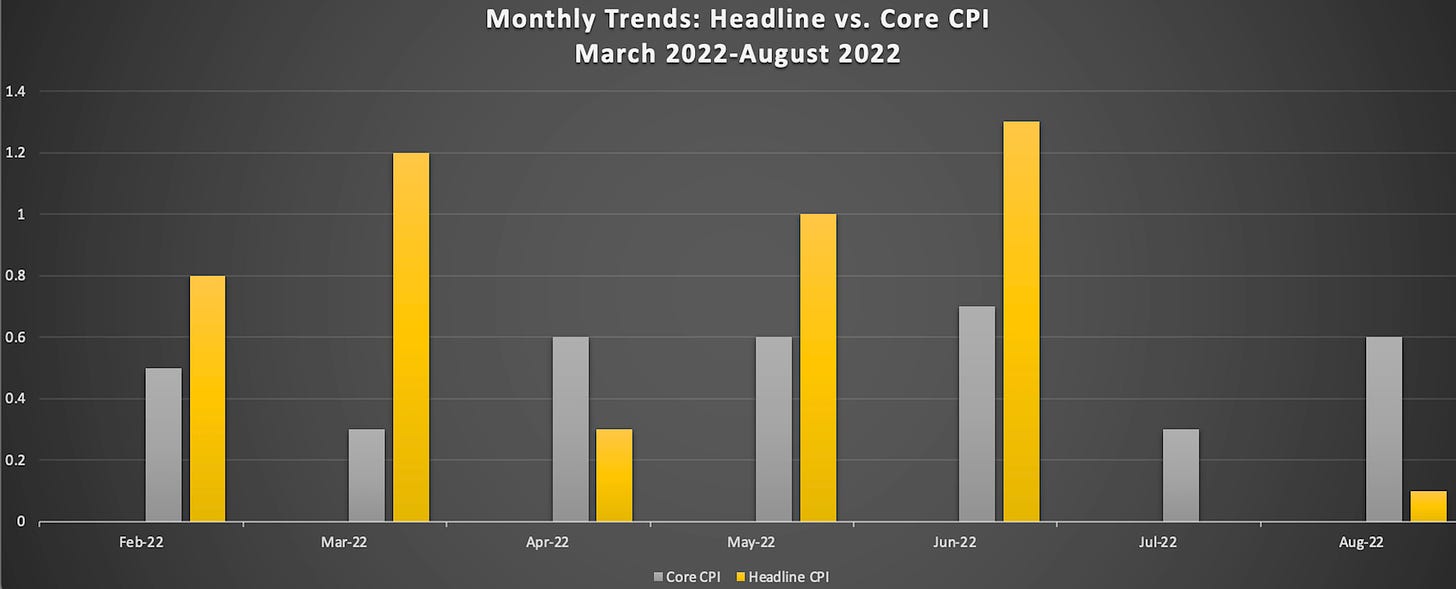

While headline inflation gave reassuring vibes, so-called core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, came in hotter than expected. On a monthly basis, core inflation doubled (from 0.3% in July to 0.6% in August). That pushed the year-over-year measure to 6.3%, which is up from the 5.9% that was reported in both June and July. A lot of people interpreted the rise as an indication that inflation might prove “stickier” and harder to bring down over time.

To be clear, this is what we’re looking at in terms of headline and core inflation, month-over-month. The move up in core to 0.6% in August puts last month’s core reading slightly behind June (0.7%) and in line with where we were in both April and May (0.6%). But it moved in the wrong direction compared with the July reading (0.3%), so naturally, everyone lost their minds.

By the time I finished teaching, markets were in turmoil. Everyone was speculating about how the Fed would respond to the hotter-than-anticipated core inflation numbers. When I checked to see what financial markets were thinking, I found them predicting a 70% chance of a 75-basis-point interest rate hike and a 30% chance that Powell & Co. take rates up by a full percentage point (100 bps) when they meet next week. The more modest 50bps hike that had been on the table when I was enjoying my breakfast appeared out of the question by 8:30 am ET, when the August inflation numbers landed.

The report spooked investors, and the stock market got crushed. A friend of mine, who is chairman of a capital management firm, sent me a note saying that he was “flummoxed” by the reaction, noting that “markets lost over a trillion dollars of value” in a single day.

I’m not in the business of trying to forecast the stock market, but I do try to anticipate where the economy is headed and that means trying (among other things) to correctly anticipate what policymakers will do.

We’ve heard Chairman Powell say time and again that the Fed is going to be “data dependent” and that he doesn’t put too much weight on any one inflation print. But I suspect that financial markets have the right beat on the Fed right now.

Even before the August report, former Fed vice chair Richard Clarida was predicting that the Fed would hike rates to 4 percent or more, “come hell or high water.” The Fed “is data dependent,” he said, “but that’s why they’re going to 4 percent. Inflation is way too high.” By now, pretty much everyone is convinced that yesterday’s report means that an already hawkish Fed is busy sharpening its talons ahead of next week’s meetings.

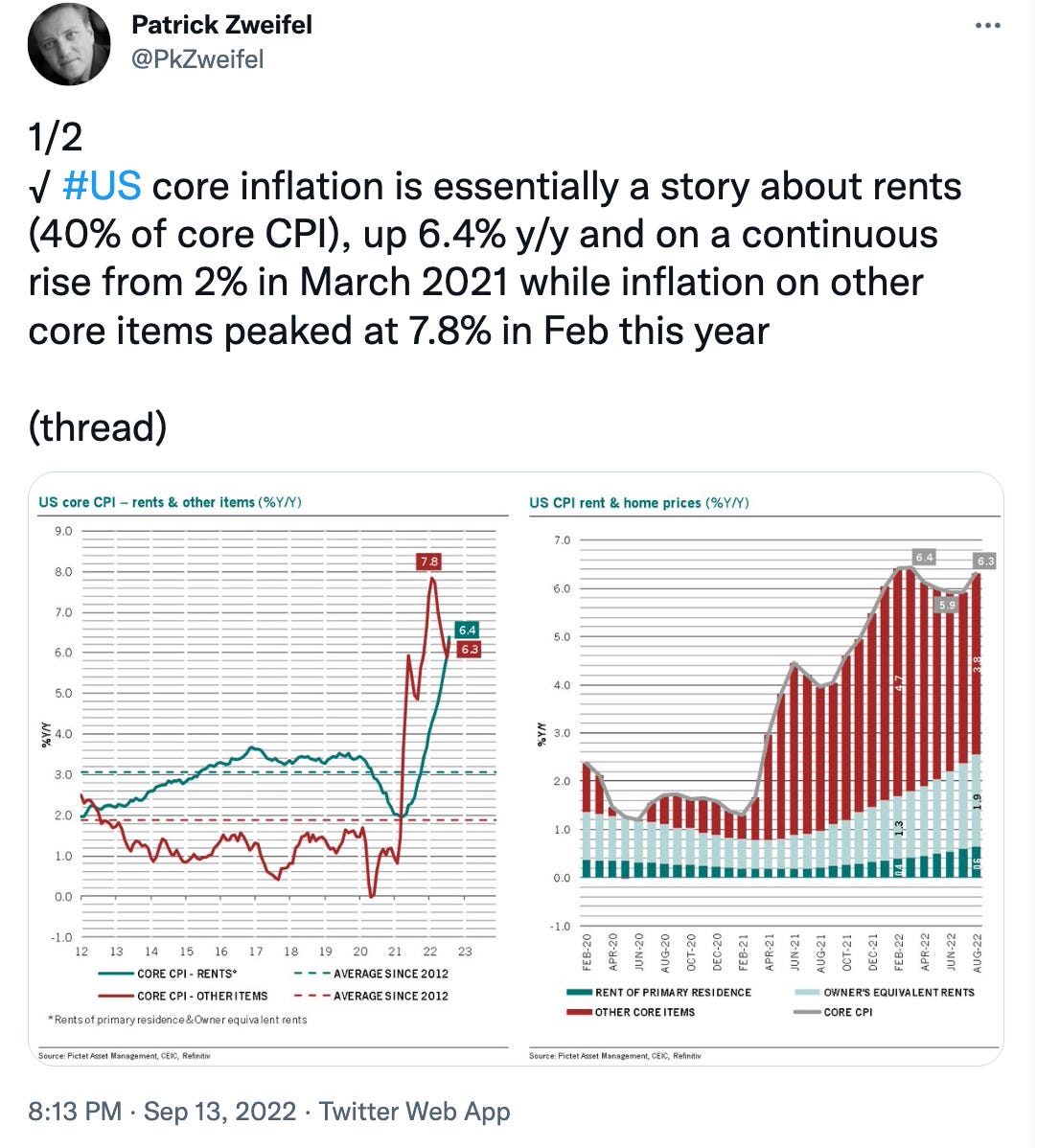

I don’t have to tell you—again—that I think that deliberately creating more unemployment is the wrong way to tackle inflation. As others have noted, a big part of the core inflation story right now is about rent inflation.

And, as Matthew Klein notes here, that’s mostly a story about what happened last year. That said, as he notes elsewhere in the thread, the shelter component of CPI may continue to get worse before it gets better.

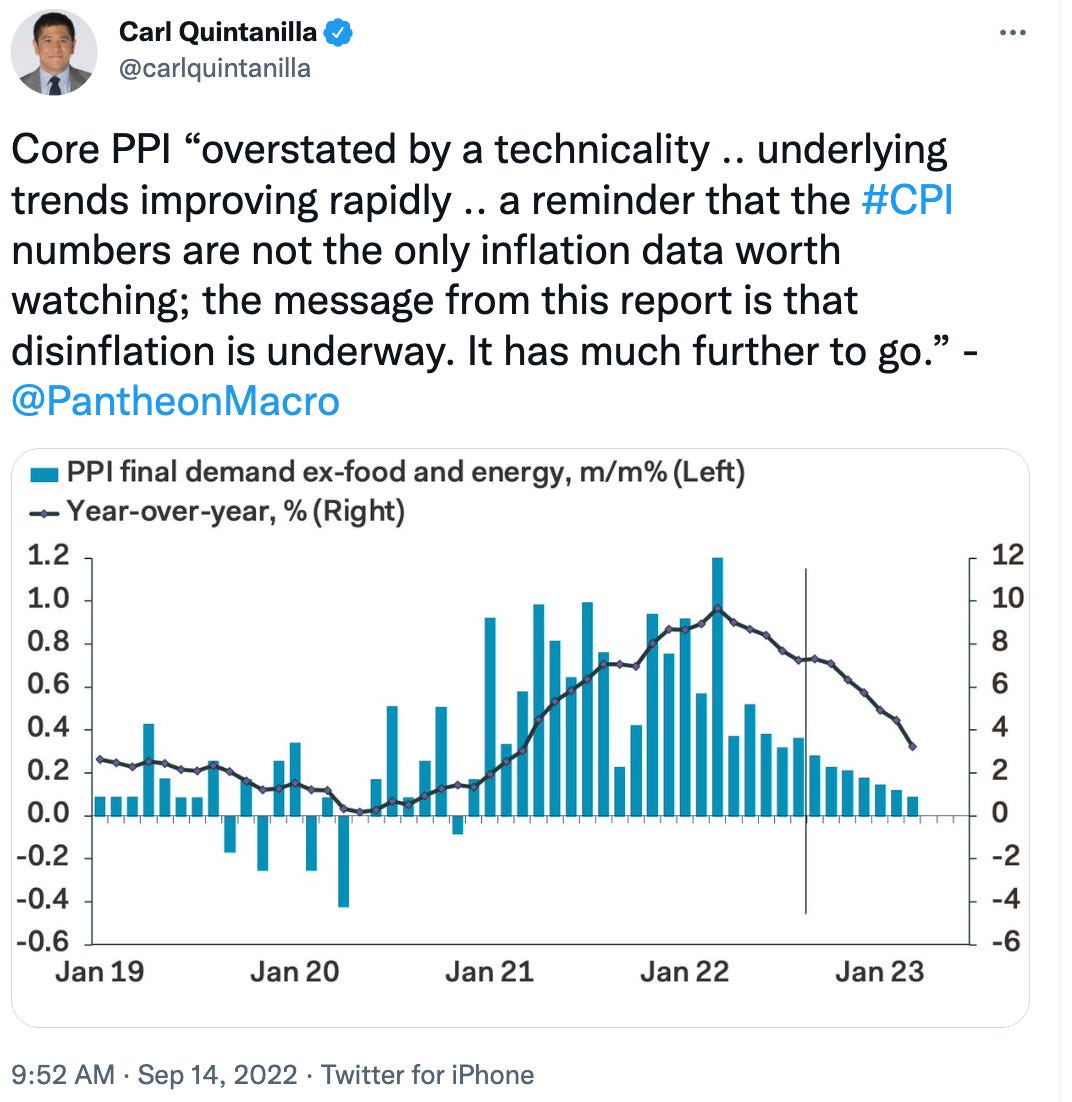

A bit of good news came this morning, with the release of another inflation index, which showed that wholesale prices fell last month. The (monthly) headline Producer’s Price Index (PPI) for August came in at -0.1%, and it was much lighter year-over-year, coming in at 8.7% compared with July’s 9.8% annualized rate. Many people think of the PPI as a leading indicator, which means that this step-down could foreshadow a more disinflationary outlook for consumer goods in the months ahead.

But, as we know, the Fed wants to see “clear and convincing evidence” that inflation is coming down. Yesterday’s report upended prospects for continued improvement on the core inflation front, all but guaranteeing that the Fed comes into its September 20-21 meeting more hawkish than ever. So, we’ll get a big rate hike next week. Odds still favor a 0.75 percentage point increase, but don’t rule out a more aggressive move. And, of course, the Fed will raise rates at its November 1-2 meeting, and it will hike again when it convenes for its final meeting of the year on December 13-14.

Buckle up! The rate hikes will continue (at least) until the economic recovery gives way to recession.

What I liked most about this post was the headline -- though perhaps for a connotation which Ms Kelton did not intend.

When I read, "The Rate Hikes Will Continue Until Morale Improves," my first thought was, "*Whose* morale has to improve?"

The average American's? The working class's? No! It's the *ruling class's morale* which has to improve before the Fed can stop hiking interest rates. The stock market as the measure of capitalist morale: I should have had that insight forty years ago!

The CPI services inflation data is highly suspect. It has diverged from PCE services inflation in a huge way. These two measures of the same sectoral inflation now diverge by more than 3 percentage points.

If we deflate nominal weekly earnings with CPI inflation, we get a gargantuan decline in real weekly earnings which supposedly have been falling at a 4% annual rate for six consecutive months now. 4%!! There has been nothing like this going back to 1981.

If real weekly earnings have been falling by a four percent annual rate for months now consumer spending should be collapsing. Maybe it has been weaker than the first pass data so far says, but we see no signs it has been collapsing.

If we do the same using the PCE services deflator we get a far more plausible 2 % decline in real income.

We should ask ourselves, why oh why would we be having a gargantuan decline in real earnings recently?

The reason is that because at turning points into recession there are sometimes many grave statistical errors which mislead, sometimes fatally. We have more this time around than in the past:

Payroll growth massively above household survey job growth

ISM services PMI booming and S&P global services PMI crashing

Implied business productivity crashing like never before in a close to constant GDP

A completely off-the-charts statistical discrepancy with net domestic income almost 5 percentage points above net domestic expenditures when in reality they are the same

And now a huge divergence in two measures of services inflation in a basically services economy

I’m spooked by my memory of 2008 when faulty data said the economy was doing just fine when in fact it had entered into the deepest and most protracted economic contraction since the 1930s.

I fear a puerile Fed, trying to be as hawkish as can be for fear the kids on the block will call it chicken, will select faulty data in a way that will support more policy rate increases even though the turning point into recession has arrived. So Stephanie is right to expect a recession and higher unemployment soon.