Like many of you, I spent some time listening to Fed Chair Powell’s recent testimony on inflation and the economy.1 Over the course of two days, Mr. Powell responded to hundreds of questions from dozens of lawmakers. Some asked about Bitcoin and other crypto currencies. Some wanted to hear about the Fed’s latest thinking on central bank digital currencies. And some were eager to talk about climate and energy policy. But these three questions were the most ubiquitous:

Why is inflation running at a 40-year high of 8.6 percent?

What is the Fed going to do about inflation?

Can the Fed bring inflation down without triggering a recession?

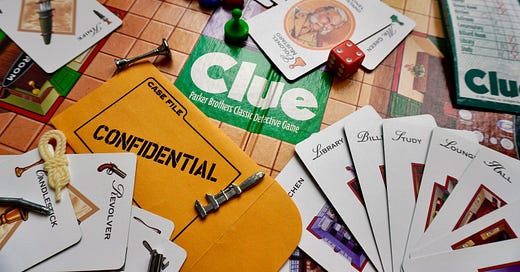

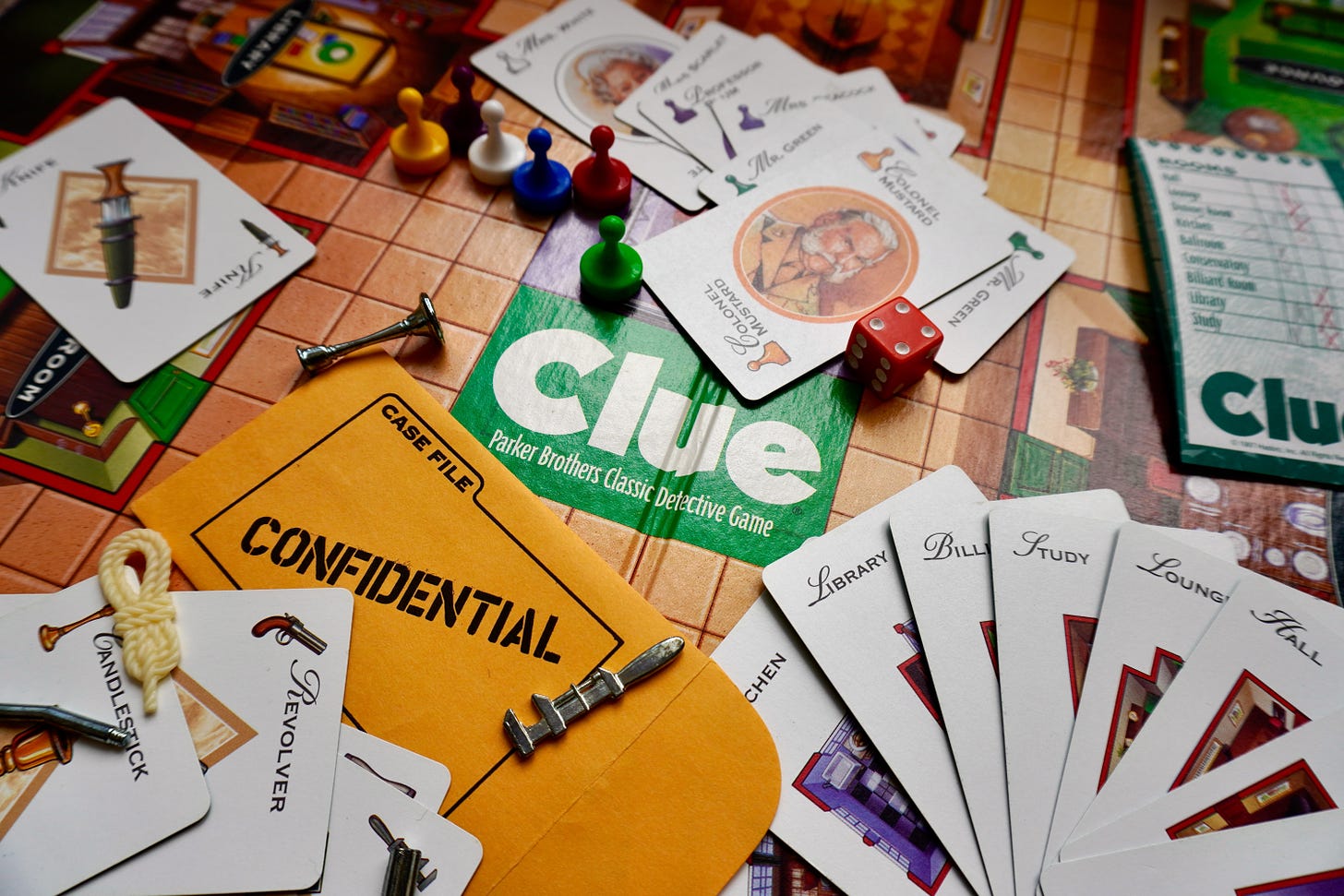

Listening to lawmakers tee up the first question, I couldn’t help but think of the classic mystery board game Clue.

Many posed an open-ended question—why do we have all of this inflation?— inviting the Fed Chairman to name the guilty party. Others attempted to lead the witness by pinning the crime on a specific malicious actor.

It was Jerome Powell in the Federal Reserve with his massive balance sheet!

It was President Biden in the White House with the American Rescue Plan!

It was Vladimir Putin in Ukraine with the tanks and the missiles!

It was corporate CEOs in their boardrooms with their price gouging!

It was COVID-19 in every corner of the globe with the fragile supply-chains!

Some, like Representative Gregory Meeks (D-NY, 05) refused to point the finger at any one culprit (25 min).

Isn’t just a massive storm of everything what contributes to inflation and causes it all over the world? It’s a little bit of everything right? . . . I would not single out any one thing. I would probably have to talk about the conglomerate of things.

He’s right, of course. As I wrote back in February, lots of different things brought us to where we are today. But saying that lots of things contributed to the spike in inflation isn’t the same as saying that each contributing factor bears an equal share of the blame. Some things matter a little bit, and some things matter a lot.

And it’s important to try—as best one can—to figure out which things added only trivially and which contributed meaningfully to the run up in inflation.

Economists are busy debating this question. As you might expect, even very smart people doing their best to untangle the conglomerate of potential contributors often arrive at starkly different conclusions. Some economists—most notably Larry Summers and Jason Furman—have consistently placed the lion’s share of the blame on excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus—especially the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA)2 passed by Congress last March. That’s not what researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found back in October, nor is it consistent with what Mark Zandi and his team at Moody’s Analytics published earlier this year.3 It’s also not consistent with new research, published just this week, by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. That research finds that “factors other than demand account for about two-thirds of recent elevated inflation.” Specifically, only about a third of the jump—1.4 percentage points—in headline PCE inflation could be traced to demand-side factors.

It’s not a debate that will be settled anytime soon—okay, it will never be settled—but it is an important one.

Why?

Because if we misdiagnose what’s driving the inflation problem, it raises the odds that we we end up choosing the wrong course of treatment. We could do something that’s ineffective or something that makes the situation even worse.

When All You Have Is A (Sledge)Hammer

And this brings me to the next set of questions that lawmakers repeatedly raised. How does the Fed plan to bring inflation down, and can it do so without throwing the economy into recession?

At this point, we all know the answer to the first of those questions. The Federal Reserve is raising interest rates, and it plans to continue to do so until … well, we don’t know exactly when it will stop tightening (or reverse course). What we do know is that Chairman Powell believes that interest rates will likely need to rise “above neutral” to a “moderately restrictive” level and that he recognizes that the economy may go into recession as financial conditions tighten.

And while that may not concern Larry Summers, who’s urging Powell to do whatever is necessary—including throwing millions out of work—to “slay the inflation dragon,” it’s a deeply troubling scenario for many other observers. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Ayana Pressley (D-MA, 07) were among the dozens of lawmakers who pressed Powell on the appropriateness of relying on the blunt instrument of interest rate hikes to treat inflation. Here’s Senator Warren:

Inflation is like an illness and the medicine needs to be tailored to the specific problem, otherwise you could make things a lot worse. Right now, the Fed has no control over the main drivers of rising prices but the Fed can slow demand by getting a lot of people fired and making families poorer.

Echoing that theme, Representative Pressley said:

The Fed has a role to play, but the wrong medicine can cause even more harm and make the patient more ill.

Powell pushed back but acknowledged that interest rates and the Fed’s balance sheet are “famously blunt and imprecise,” which led Pressley to observe:

There’s an old adage that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail… The Fed knows that raising interest rates will not address the root causes of rising prices…we need a more sophisticated toolkit.

Like many of the democrats who questioned Powell, Pressley is worried about the inevitable collateral damage—on people’s lives and livelihoods—that comes from swinging around an imprecise sledgehammer. Instead of hiking the overnight interest rate and allowing it to indiscriminately raise borrowing costs across the whole of our economy, Pressley suggested that it might be useful for Congress to pass legislation that expands the Fed’s toolkit so that it would be able to “tailor a more precise response to inflation.” Her time expired before she could fully elaborate, but she did hint at what an expanded toolkit might include:

Regulating the availability of credit in the specific sectors of the economy experiencing high inflation without impacting other sectors.

Hearing that, I immediately thought of this report published by MMT scholar Nathan Tankus back in January. The ideas are worth thinking about, even if we’re not likely to see a change in the toolkit anytime soon.

For now, we’re stuck in a world where far too many people remain convinced that conventional monetary is the best weapon against inflation. Perhaps we’ll get lucky and inflation will trend steadily down before the proactive efforts to rein it in tip the economy into recession. But, as I’ve written before, I wouldn’t bet on it.

I think we need a different approach.

That’s the package that re-upped federal unemployment assistance, sent out those $1,400 checks, and delivered monthly cash assistance to families with kids under the age of 18 (the expanded Child Tax Credit).

MR. VOLCKER: The Federal Reserve has a long history with operating

credit controls.

MS. FOX: From war time.

MR. VOLCKER: And they went on for 10 years more after the war.

Mortgage & consumer credit controls went on for quite a long while.

We should still have them. [Laughter] 72

--As cited from Tankus, 2022, "The New Monetary Policy." Modern Money

Network.

On the simple side, I'll just say that I think we've figured out how to not have recession, we just pump money into the system. So the problems that methodology creates are apparently less painful than recession? For the last 14 years or so, we've talked about raising the interest rate. At the first hint of economic slowdown, we stop raising the rate, or even lower it. And if the slowdown, or the threat of slowdown, persists? Well, pump some money directly into the systems. Say, like $5 trillion+ for Covid relief. I'm not saying good or bad, just that it seems that's where we are.