Before we dive in, let’s get one thing straight. Social Security is a federal program that was created under the Social Security Act of 1935. It was established as part of the New Deal by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a “dedicated revenue” in the form of a payroll tax. Today, employees and their employers each pay 6.2% of wages up to a taxable maximum of $176,100 (2025) into Social Security.1

I’ve been publishing academic and popular articles on Social Security for at least 25 years, trying—unsuccessfully—to shift the public debate away from concerns over “financial solvency” toward a focus on inflation risk and real resources. As far as I’m concerned, any lawmaker, journalist, or media pundit who talks about Social Security without distinguishing between the following challenges isn’t being honest with American people.

1.) Legal Authority to Pay — Under current law, Social Security can only pay full scheduled benefits if there is enough earmarked funding to do so. Put simply, there must be enough “cash” coming in via payroll tax withholdings or enough “cash” coming in plus “cash” in the Social Security Trust Fund to cover the full cost of paying benefits each year. If the trust funds run dry—i.e. are drawn down to zero—then the program doesn’t have the legal authority (from Congress) to pay full benefits. This would force automatic cuts under current law.2

2.) Financial Ability to Pay— As Alan Greenspan explained under oath many years ago, the federal government cannot “run out of money.” One does not have to embrace Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to acknowledge that Congress has the financial ability to “create as much money as it wants and pay it to someone,” as Greenspan put it. Social Security is a federal program, authorized to pay benefits to eligible individuals—retirees, their dependents, and the disabled—under the rules established by Congress. The reason there is so much anxiety about Social Security “running out of money” is that the authority to pay benefits is constrained by statute. If Congress changed the law to give Social Security permission to pay full scheduled benefits regardless of any earmarked source of funding, then the threat of automatic cuts would disappear.

3.) Capacity to Provide Real Resources—This is where the rubber meets the road, and this is what MMT economists emphasize. It is easy enough for a currency-issuing government, like the United States, to meet financial obligations that are denominated in a sovereign unit of account. That’s true whether we’re talking about paying trillions of dollars in interest on government securities or trillions in the form of benefits to future retirees. In purely financial terms all of it is “affordable.” But what about in real terms? Greenspan understood this distinction quite well. How can you be sure, he asked, “that the real assets are created which those benefits are employed to purchase?” In other words, what happens after the checks go out and retirees—who are no longer helping to produce the economy’s output—want to book vacations, dine out, play golf, get medical treatment, and so on? With fewer workers and more retirees, the real challenge is this: Will the economy be productive enough, in the year’s ahead, to allow both groups to buy the things they want or will everyone end up competing over a shrinking pool of real resources, thereby driving up prices?

Running Out of Money

If we were having an honest debate, we would acknowledge that Social Security can run out of statutory headroom to pay full scheduled benefits, but the money can always be made available. Alas, we’ve become trapped in an eternal tug-of-war over the program’s “solvency,” not unlike two desperate souls fighting over rocks in Dante’s Fourth Circle of Hell.

Everyone just accepts that the program is “running out of money,” so there’s a never-ending battle over the best way to shore up the program’s finances. It’s not the debate I want to have, but it’s the only one that gets any serious consideration.

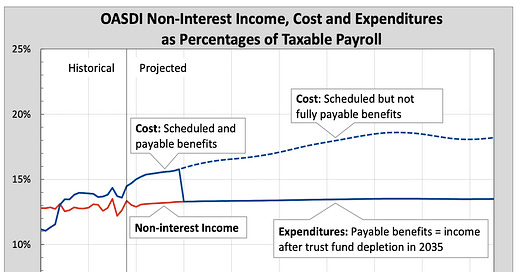

So it’s worth understanding how the Social Security Administration (SSA) determines how much runway is left before the program “runs out of money.” It’s actually a pretty big undertaking, and it requires the Trustees of the SSA to make a wide array of economic and demographic assumptions in order to project how much money the program will take in—and pay out—in future years. Here’s a projection from the chief actuary of the SSA, Stephen Goss.

There’s enough “money” to pay full scheduled benefits until 2035. After that, the combined (OASDI) trust fund (which doesn’t actually exist), is depleted and the program is only legally authorized to pay 83% of scheduled benefits. The “good news” is that this is projected to happen 13 months later than the Trustee’s were forecasting in their previous year’s report.

If that seems like a pretty big “miss,” it’s because it’s hard to predict exactly what’s going to happen to things like inflation, unemployment, economic growth, worker productivity, fertility and mortality rates, immigration, etc. Relatively small changes in the underlying assumptions can have a big impact on the size and timing of projected shortfalls.3

The Shortfalls Weren’t Supposed to Happen

Back in 1983, following the prescriptions of the Greenspan Commission, changes were made that were supposed to prevent Social Security from “running out of money” over the next 75+ years. Yet here we are, in the Fourth Circle of Hell, wringing our hands over looming shortfalls and automatic benefit cuts. Why is that? As Stephen Goss put it:

Well, it turns out that some things are easier to predict than others. As Goss explains, it’s not that people are living longer than expected. In fact, “projected life expectancy at age 65 in the 1983 report was extremely accurate.” It’s also not because of an unexpected decline in birth rates, for “this was also known and anticipated in 1983.”

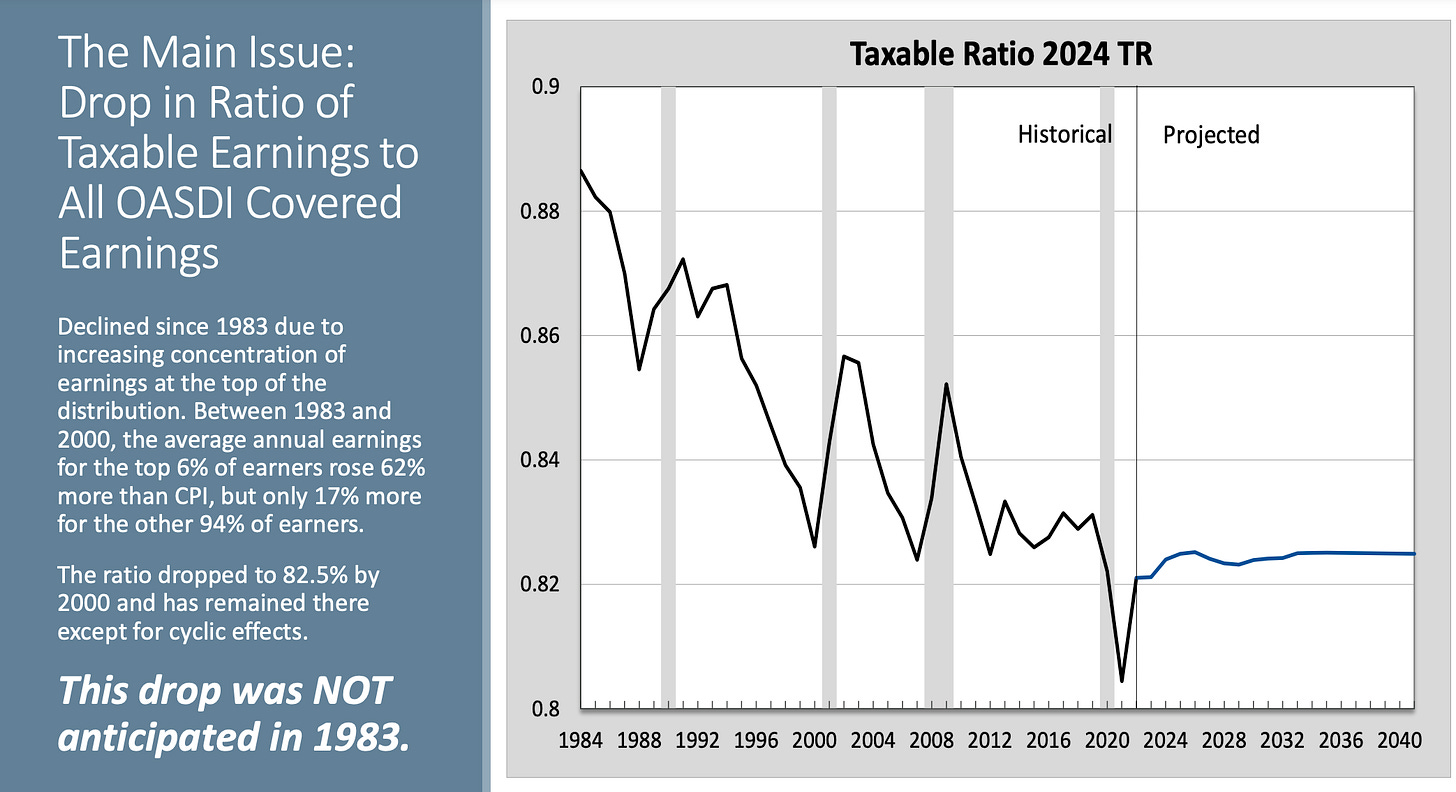

The main issue—what the Greenspan Commission did not see coming—was Elon Musk. Or, more specifically, the “increasing concentration of earnings at the top of the distribution.” As Goss explains:

“The reduced share of earnings subject to payroll tax explains most of the increase in cost as percent of payroll, compared to the 1983 projection.” In other words, rising inequality is the main reason that Social Security appears to be in financial trouble.

Bottom Line

The bottom line is that if you want to engage productively in the debate over Social Security, you need to understand the difference between legal authority to pay, financial ability to pay, and real resource capacity. If you simply want to understand why pretty much everyone believes the program is “running out of money,” you need to understand how the Trustees formulate their projections. And if you want to understand why the Trustees continue to project shortfalls when the whole “problem” was supposedly resolved back in 1983, you need to understand the one big thing the Greenspan Commission didn’t see coming: the rise of Elon Musk.4

The self-employed pay 12.4%, since they’re paying the employee and employer side. While benefits are highly progressive, the payroll tax itself is by far and away the most regressive tax in America. The income cap means that if you earn $1,00,000 a year, the first $176,100 is subject to the payroll tax, while the remaining $823,900 escapes it.

The Social Security Administration estimates that Social Security can pay 83% of scheduled benefits after trust fund depletion in 2035 and 73% of scheduled benefits in 2098.

For example, over the past 13 years (2012–2024), the Trustees have projected that the Social Security Trust Fund (OASDI) would be depleted sometime between 2033 and 2035. ut over the past 30 years (1995–2024), they thought this could happen as early as 2029 or as late as 2042.

Let’s circulate this extremely important “explainer” now, as Musk et.al., who clearly has less than zero understanding of public finance, distorts and misleads -and as the Congress is willingly and thoughtlessly misled while making extraordinarily consequential budget decisions.

I was a blue collar rank and file union activist for close to 30 years as well as being a local Dem campaign mgr. I fought the unfriendly takeover in the late '70s by neolibs. Who subsequently dumped the New Deal and the majority working class. I've read solid academic research that confirmed my personal experiences. Like the robust stats in Les Leopold's 2024 //Wall Street's War on Workers ( How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do about It)//. He begged the Ds to take up this potentially winning issue. Of course the D elite ignored it just as they have ignored us workers for 40 years.

Figuring out what happened required reading econ history. Including about Keynes and books on New Deal economics like //Saving Capitalism: The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the New Deal// by James Stewart Olson. As well as about the Austrian School plus {shudder} Friedman and the now dominant Chicago School.

I had assumed the issue was how econ data were interpreted; of course progressives would see the same reality quite differently than conservatives. I was shocked to discover the Chi School is almost entirely about assumptions and assertions of the kind exemplified by Thatcher's infamous "there are no alternatives." Its foundations consist of little more than a deep hatred of the New Deal by '30s era heirs of the Robber Barons and their contemporary incarnations. Very little is based on empirical evidence. Of course they're able to quiet us peasants because they wave around scary looking formulae.

I KNEW there certainly were alternatives! I've just finished Steve Keen's latest and your wonderfully done MMT--language not scary, but inviting. I'm in the middle of //MMT and Its Critics//by Fullbrook and Morgan. Like so many others of my class, I have no pension and live on SSA as very low income. I had to cancel a subscription to afford this one. However, nothing is more important than econ structures. Especially since entire governments now function as mere subsidiaries.