Every August, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City hosts a three-day gathering that brings together central bankers, academics, policymakers, journalists and various others from around the world. You might have heard it referred to as the Jackson Hole meeting because it takes place at the Jackson Lake Lodge in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. If you’re curious about why they meet in Wyoming instead of Kansas City, Missouri where the KC Fed is located, here’s the answer from Axios’ Neil Irwin.

Why Jackson Hole? In the early 1980s, the Kansas City Fed leaders learned that the best way to ensure Fed chairman Paul Volcker would accept an invitation was to locate the event somewhere with good fly fishing in late August. Jackson Hole it was.

There will be various papers presented and panel discussions, but the really big question is always, ‘What will the Fed Chair say?’ Here’s the speech Jerome Powell delivered at last year’s gathering. And here’s the passage that moved markets and dominated headlines for days.

Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.

Powell went on to characterize the labor market as “extremely tight,” noting that inflation was “running far above” the Fed’s 2 percent target. He described the elevated inflation as “the product of strong demand and constrained supply,” and he acknowledged that “the Fed's tools work principally on aggregate demand.” But he insisted that the Fed would do whatever it needed to do—including inflicting pain on American households and businesses—in order to bring inflation back down. The Federal Reserve’s “responsibility to deliver price stability is unconditional,” he said.

By the end of the trading day, Powell had succeeded in doling out some pain. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 1,008.38 points (or 3%), the S&P 500 fell 141.46 points (or 3.4%), and the Nasdaq tanked 497.56 points (or 3.9%). But what about the broader pain that was supposed to clobber households and businesses?

It’s been almost exactly one year since Powell delivered The Pain Speech and…well…mercifully, the macro picture hasn’t evolved the way he anticipated.

When Powell gave his remarks, the unemployment rate stood at 3.5 percent. As he saw it, the labor market was severely out of whack, with way too many job vacancies relative to the number of job seekers. Powell insisted that the only way to bring inflation down was to deliberately stifle growth and “soften the labor market” (i.e. push the unemployment rate higher). Since then, the Fed has raised its target interest rate from a range of 1.5-1.75 to a range of 5.25-5.50. And where is the unemployment rate today? You guessed it, 3.5 percent.

On top of that, the labor force participation rate (LFPR) is higher (62.1 percent then vs 62.2 percent today), the employment-to-population ratio (EPoP) is higher (60.0 percent then vs 60.4 percent today), the black unemployment rate is lower (6 percent then vs 5.8 percent today), and youth unemployment (16-19 yrs) is lower (11.5 percent then vs 11.3 percent today). Wage growth is decelerating, but the sharp decline in inflation means that real wages for most workers are now higher than they were before the pandemic. Take a bow, labor market.1

On the inflation front, we had a solid year of disinflation until last month’s headline number ticked higher (YoY) after the 0% read from July 2022 dropped out and the 0.2% rise in July 2023 got included. Everyone knew it was coming, and the YoY number (3.2%) still came in lower than expected, but it ended our nice twelve-month march lower on headline CPI. Alas, we may see it happen again as commodity prices move higher and we wait for the fall in shelter prices to work their (lagged) way through. I wrote about this last week. Still, the blue line shows you how incredibly far we have come over the last year. Core CPI (red line) also continues show steady improvement, even as things like retail sales surprise to the upside.

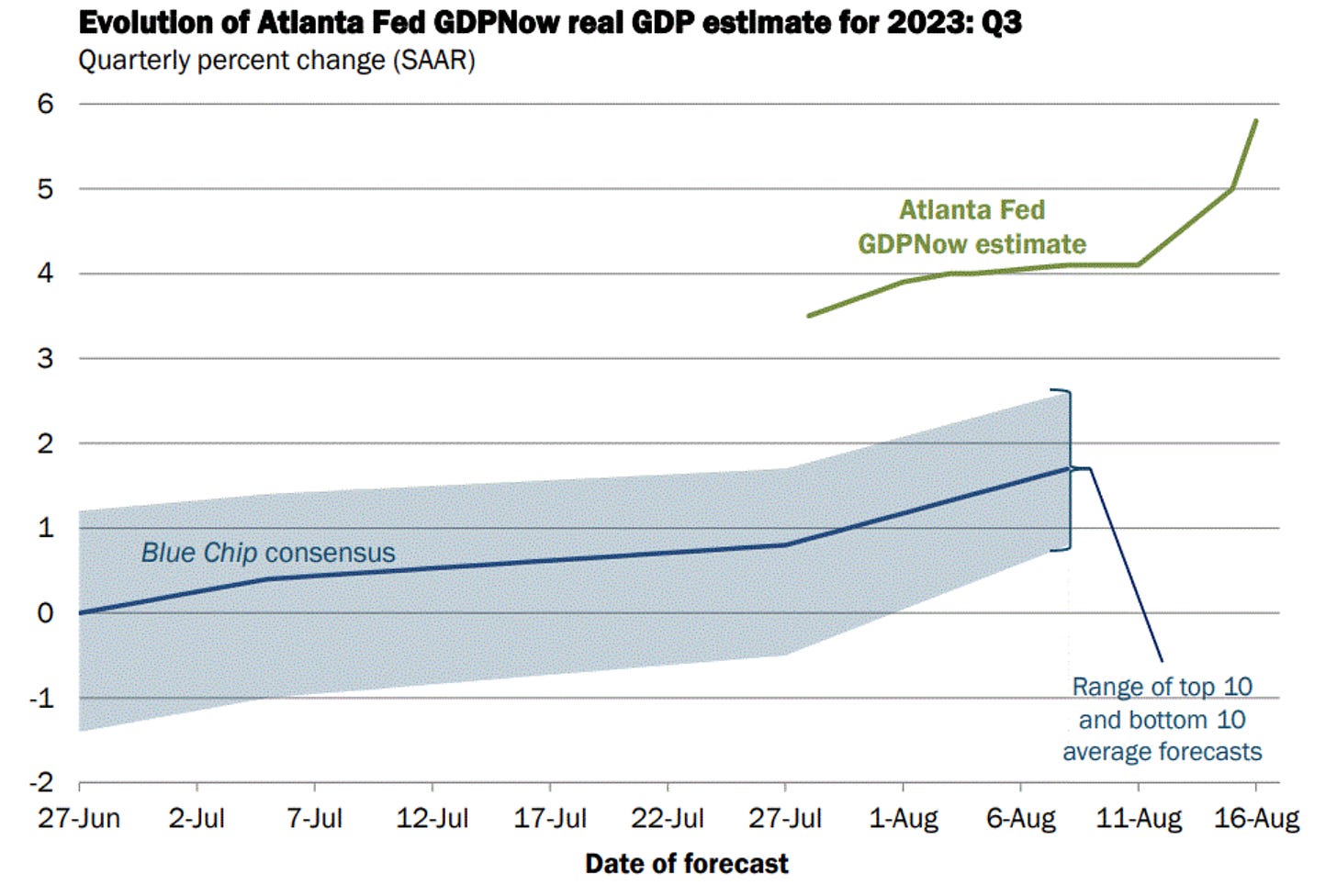

Here’s the latest estimate for real GDP growth from the Atlanta Fed’s real GDPNow model. It has the US economy on track to grow at whopping 5.8 percent in the third quarter of this year. Remember, that’s inflation-adjusted (or real GDP) growth. Yes, it tends to have an upside bias, but it continues to signal robust (and strengthening) aggregate demand.

So where is all of this robust demand coming from? Part of it is coming from the investment component of GDP. There’s a bonafide boom in real (inflation-adjusted) non-residential construction spending underway. I wrote about some of the other drivers here. Will the small uptick in inflation and the big jump in forecasted growth embolden those who repeatedly called for higher unemployment to tame inflation? Will it spook the Fed into hiking this fall and perhaps into the winter?

If you’re a loyal reader of The Lens (thank you!), then you probably already know my view. Like former Vice-Chairman Alan Blinder, I don’t give the Fed credit for bringing inflation down from 9.1 percent (June 2022) to 3.2 percent (July 2023). It largely came down on its own, as the economy worked through some of the pandemic-induced bottlenecks, shortages and labor market dislocations. That’s what tran·si·to·ry meant. And, President Biden just pointed to another source of cooling inflationary pressures.

But I never thought the problem was too many people working or working people making too much money. And one reason we’ve seen inflation fall by two thirds without losing jobs is that we’re seeing corporate profits come back to — down to earth.

Of course Powell will not say that the rate hikes have been mostly irrelevant in terms of bringing down inflation, nor will he point to their role in driving up the fiscal deficit. But as some of us have been pointing out for a while now, higher interest rates can feed inflationary pressures via the interest-income channel, mark-up pricing (interest is a cost for millions of firms that borrow to finance working capital, etc.), and reduced supply/capacity (e.g. housing units that don’t get built).

That said, I think it’s pretty easy to anticipate what Powell will say at this year’s gathering. We’ve made substantial progress. But there is more work to do. We are firmly committed to brining inflation all the way back down to 2 percent. We’re not going to declare victory and go fishing.

Unfortunately, they’re not done.

The power of Big Fiscal at work.

Key citation: 'Powell insisted that the only way to bring inflation down was to deliberately stifle growth and “soften the labor market” (i.e. push the unemployment rate higher)'. In his eyes, apparently, the only significant driver of inflation is raising wages and the only cure is increased unemployment. In other words, the major role of the central bank is to maintain or increase the level of inequality.

Can anyone out there explain how higher interest rates can counterintuitively lead to HIGHER inflation? I understand that higher interest income increases spending power, but isn't the vast majority of this income accruing to the top 10%? They've already bought all the toothpaste and toilet paper they need, and I don't care if they spend it on a new yacht or a summer home on Martha's Vineyard. So why would this interest income put pressure on the prices of necessities?