Some Very Quick Thoughts on Today's Inflation Report

I'll be discussing at 8:30 am ET on CNBC's Squawk Box tomorrow

Today’s CPI report reaffirms what we already knew. The U.S. economy is shaking off the effects of the pandemic-induced spike in inflation.

Inflation is moderating. It is not sticky. There was never a wage-price spiral at work. As James Galbraith put it in this Project Syndicate column yesterday:

Back in 2021 and early 2022, a posse of prominent economists – including Lawrence H. Summers, Jason Furman, and Kenneth Rogoff, all of Harvard – criticized the Biden administration’s fiscal and investment program, and pressured the US Federal Reserve to raise interest rates. Their argument was that inflation, fueled by federal spending, would prove “persistent,” requiring a sustained shift to austerity. Unemployment, sadly, would have to rise to at least 6.5% for several years, according to one study touted by Furman.

Lucky for us, that proved incorrect. Unemployment is down to 3.5%, the latest estimate from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model has real GDP growth tracking at 4.1% in 2023Q3, and inflation continues to moderate. It wasn’t “persistent.” It was, as I said 2021, transitory.

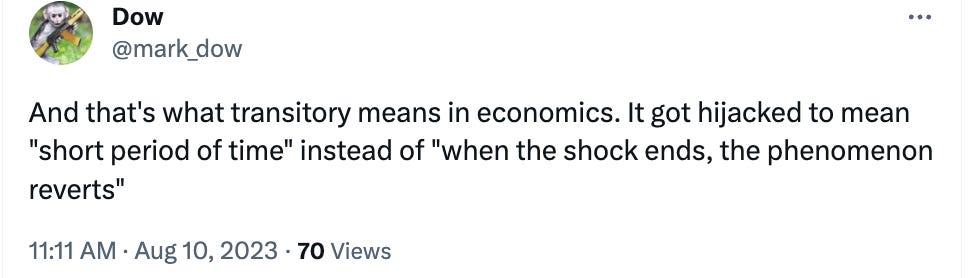

Here’s a nice chart from Julia Coronado and some commentary from Mark Dow, making the same point.

Here’s a snapshot from today’s inflation report.

And some quick takeaways.

Yes, YoY ticked up from 3.0% to 3.2% (which was less than expected), but we know the increase was about the weirdness of lagged effects. It’s almost entirely due to what’s happening with core services, which includes lagging rent prices.

The trend is our friend.

Core CPI over the last 3 months annualizes to 3%. That’s the lowest since summer 2021. We’ll probably see a two-handle soon, and it looks like we’ll get there without the spike in unemployment that certain folks insisted was necessary to wrestle inflation back down. And core PCE usually runs a bit below core CPI, so we’re in the vicinity of the Fed’s 2% target.

The last two core CPI prints have been running below the Fed’s target. If you just look at the last two months, we’re actually at pre-pandemic levels on core inflation.

The index for shelter contributed a whopping 90% of the July increase in headline inflation. That should moderate in the coming months.

Core services ex shelter—Powell’s preferred inflation metric—is running at 2.9% on a 6-mo annualized basis.

We’re seeing an acceleration of deflation in core goods, which is likely to continue with the deterioration in Chinese exports.

Hopefully, we continue to see rent inflation moderate. July rent inflation was lowest since late 2021. Gotta hope that continues.

Used car prices should decline more. Airfares are coming down, rental car prices, etc. All good news on the pandemic-induced inflation-moderation front.

The thing that could throw us for a bit of a loop is the recent jump in oil prices, since it can feed pretty quickly into other categories, especially food.

There’s really nothing in this report that gives the Fed any ammunition to justify a September rate hike. The markets aren’t expecting it, and neither am I.

The thing that people are finally starting to talk about are the fiscal effects of the Fed’s rate hikes, which provide an additional tailwind on top of the CHIPS and Science Act, infrastructure, and climate bills. We can debate the magnitude of the stimulus the rate hikes are providing, but it’s not zero. It makes recession less likely in the sense that the rate hikes are boosting payments to the private sector. Does that mean a recession is out of the question? No. As Galbraith warns, fiscal austerity is one way to upend the party.

Another suggestion comes from Warren Mosler – the godfather of Modern Monetary Theory – who notes that US national debt has risen to nearly 130% of GDP, up from about 60% in the early 2000s. The net interest paid on that debt increased by 35% from 2021 to 2022 – reaching 2% of GDP – and about 70% of those payments went to the US private sector. If one adds the effect of interest paid (starting in 2008) on $3 trillion in bank reserves, the fiscal support through this channel has been substantial.

History supports Mosler’s conjecture. Back in 1981, US federal debt was only about 30% of GDP, and much of it was in fixed-interest, long-term bonds, with no interest paid on bank reserves. As a result, then Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s shockingly large interest-rate increases mostly hit private debtors and business investment, and the offsetting fiscal boost from interest payments was small.

In contrast, when the federal debt exceeded 100% of GDP in 1946, almost all of it was in war bonds held by US households. Despite yielding only 2% in interest, those bonds provided a boost to private incomes and a base for mortgage borrowing through the 1950s – a time of largely stable middle-class prosperity.

The “fiscal channel” for interest-rate payments is an inconvenient concept for those who wring their hands over the “burden” of public debt. It suggests that Powell’s rate hikes may be powerless to slow GDP. Indeed, additional rate increases could even be expansionary, at least up to a point.

Galbraith’s last line is key.

At some point the rate hikes can—and, I suspect, likely will—trigger problems that overwhelm the fiscal tailwinds. But it can take a while for the rate hikes to sow the seeds of destruction, and you never know when the reversal will come. Commercial real estate (office in particular) is a slow-motion train wreck. Aggressive tightening cycles tend to eventually expose vulnerabilities lurking in the shadows. For now, we wait.

Big fiscal works, austerity and massive unemployment don't. Indeed luckily for us, with programs such as the IRA, Chips, infrastructure bill and the crazy regressive stimulus via the fed rate hikes we've held off a recession. It also helped that supply chain pressures improved and a huge drop in gas prices as well. Disinflation is happening even on the core side despite nagging rent and shelter costs. There is no wage price spiral and even real wages are up. The less we pay attention to the likes of summers and furman the better off the economy will be.

I have a dream - as someone once said.

Stephanie would make a great president. Being a Congressional representative for a few terms may be a suitable initial step on that journey? 🙂