There were six references to the the government deficit in President Biden’s state of the union address on Tuesday night. Two of them were about blaming Republicans for adding to the deficit with past tax cuts:

But that trickle-down theory led to weaker economic growth, lower wages, bigger deficits, and the widest gap between those at the top and everyone else in nearly a century.

The previous Administration not only ballooned the deficit with tax cuts for the very wealthy and corporations, it undermined the watchdogs whose job was to keep pandemic relief funds from being wasted.

Two of them focused on how the president’s agenda could be carried out in a way that would reduce future deficits:

My plan to fight inflation will lower your costs and lower the deficit.

My plan will not only lower costs to give families a fair shot, it will lower the deficit.

And two called attention to how much the deficit is falling today under Biden’s tenure:

By the end of this year, the deficit will be down to less than half what it was before I took office.

The only president ever to cut the deficit by more than one trillion dollars in a single year.

I have six thoughts.

First, government deficits were the key to ending the pandemic-induced recession. They are the reason the recession was the shortest on record. They are the reason poverty fell to its lowest rate on record in 2020. They are the reason President Biden was able to boast about presiding over an economy that has created more jobs in a single year—6.5 million—than at any time in in the history of America. And they are the reason Fed Chair Powell was able to declare that “we have the strongest economy in the world now.” Instead of making deficit reduction a centerpiece of the president’s agenda, we should embrace the healing power of fiscal policy and work to educate the American people about how deficits can (and must) be used to deliver an economic agenda that tackles the many intersecting crises we face today.

Second, there’s nothing inherently desirable about reducing the deficit. As Abba Lerner explained decades ago, the government should never target the deficit per se, and we should never get emotional about any particular number that falls out of the budget box. A fiscal deficit is not “worse” than a balanced budget or a fiscal surplus. As I wrote in my book, “we should accept any budget outcome that delivers broadly balanced conditions in our economy.”

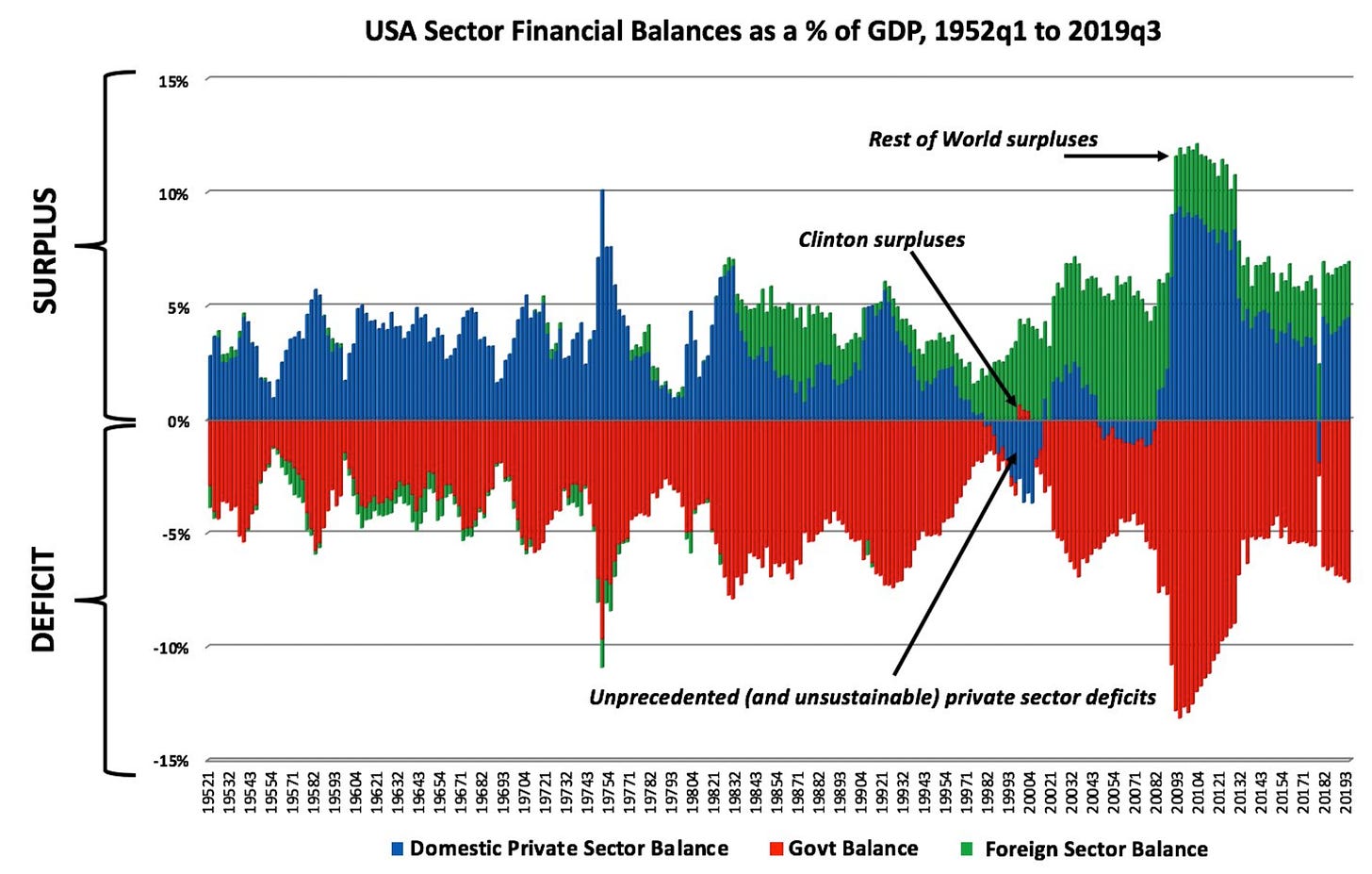

Third, for a country like the US—one that runs persistent current account deficits—government deficits are perfectly normal and almost always necessary to achieve healthy economic outcomes.1 That doesn’t mean budget surpluses are impossible—we saw them under the Clinton administration 1998-2001—but it does make them unsustainable, as Wynne Godley and Randall Wray warned. The reality is that government deficits play a vital role in supporting aggregate income, business profits, and employment. For all of the reasons outlined by Godley and Wray, we would be hard-pressed to sustain (over long periods of time) a close approximation to full employment without them.

Fourth, this thing we call a government “deficit” is just the difference (G-T) between two numbers. One number tells us how many dollars the government disperses into our hands each year (G) and the other tells us how many dollars it subtracts away from us, mostly through taxation (T). A fiscal “deficit” happens when the government puts in more dollars than it removes (G>T). We can refer to it as a “government deficit,” or we can call it a “non-government surplus.” As Godley’s sector financial balance framework reminds us, they’re two sides of the same coin. By announcing that his plan would reduce the government’s red ink, Biden is telling us that he wants to shrink the size of the annual surplus that goes to the non-government part of the economy— i.e. the US private sector (in blue) together with the rest of the world (in green).

Fifth, although the three balances must always sum exactly to zero, neither the president nor Congress can actually control how much red ink gets spilled each year. Biden can claim that his plan will lower the deficit, but the number that ends up falling out of the budget box in the years ahead will depend on a wide array of forces that are largely beyond the government’s control. As MMT economist Randall Wray put it:

[T]he deficit itself is not an entirely discretionary variable. Congress can decide to spend less (or more) and to raise or lower tax rates, but the impact on the deficit and the debt ratio is not under direct control. For example attempts to lower the deficit could be counterproductive as they could lower the rate of growth of GDP and thus increase the budget deficit as private sector spending declines. On the other hand, while it is usually believed that a large increase of government spending (say, a fiscal stimulus package, or spending for a Green New Deal initiative) would increase the deficit and lead to a larger debt ratio, the actual budgetary outcome will depend in complex ways on the impact on economic growth, as well as on how the other two main sectors respond to such changes.

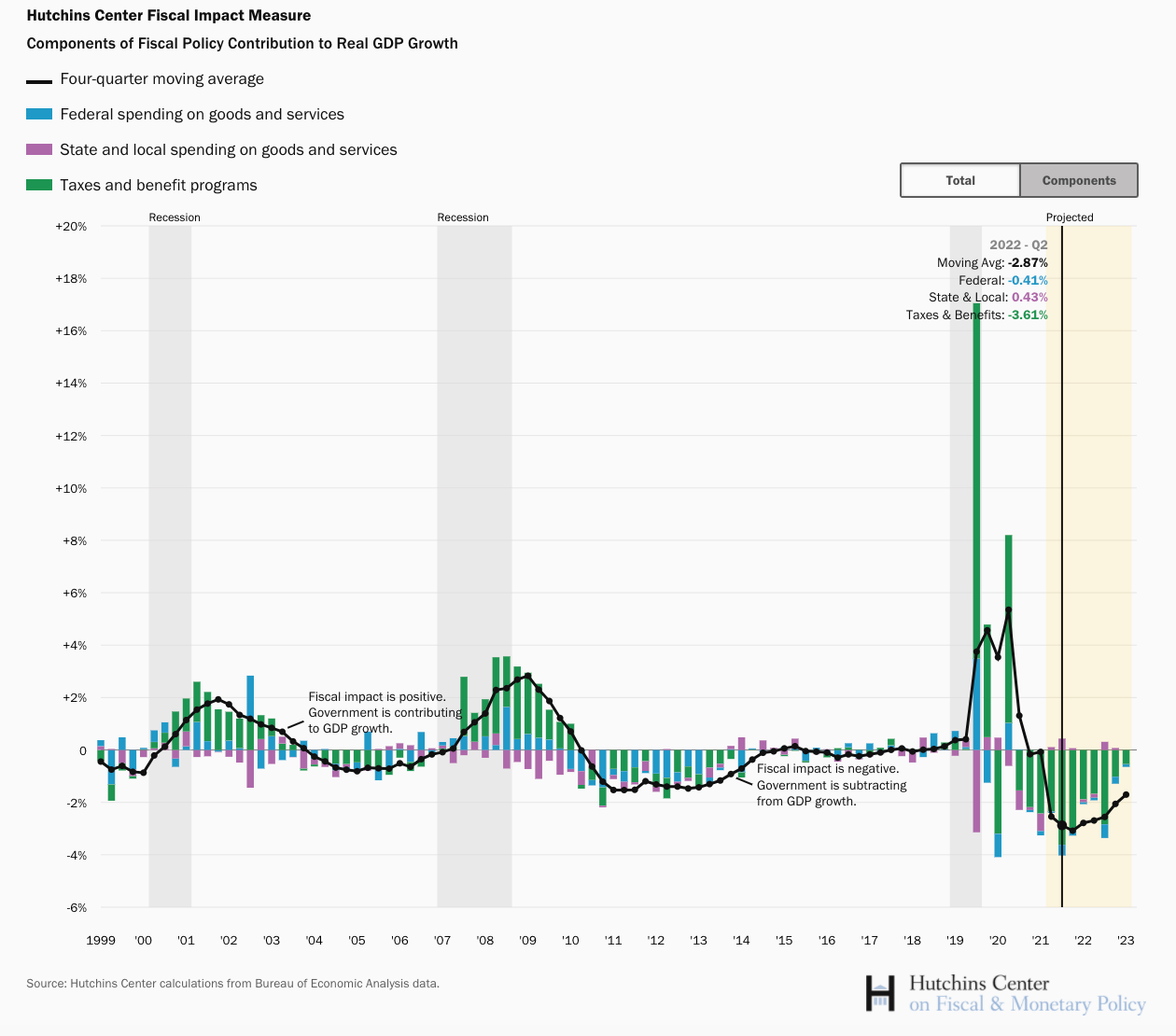

Right now, as the Hutchins Center’s Fiscal Impact Measure shows, the rapidly shrinking government deficit is acting as a drag on the economy. It’s not nearly enough to snuff out the recovery, because private sector demand has been strong enough to more than offset the fiscal drag. Still, the combined impact of state, local, and federal fiscal policy did shave an estimated 3.3 percentage points off of GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2021. Biden should be mindful about actively trying to shrink the deficit even faster.

Sixth, there’s a lot of speculation that the president decided to play up deficit reduction in an effort to bring Senator Manchin back to the negotiating table. Here’s The Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey:

The move seems designed to persuade just one guy—Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia—to sign on to parts of the president’s Build Back Better proposal.

According to POLITICO, it may have worked. Within hours of hearing the president commit to a slimmed-down spending program that would lower the deficit, Manchin reportedly “assembled a counteroffer.”

This new emphasis might give wonks and Hill staffers flashbacks. Not so long ago, a new progressive president, struggling to hold his coalition together, pivoted to austerity soon after a once-in-a-generation recession, and mired working families in a lost half decade.

Manchin has supposedly signed off on a subset of Biden’s priorities that were in the Build Back Better Act (which the senator singlehandedly killed back in December). The caveat is that he wants all of the spending to be “paid for” and he wants half of any new revenue (or cost savings) to go to deficit reduction.

So here we go again.

I don’t know whether this is another Lucy-and-the-football moment, but a big part of the reason we’re mired in this never-ending battle over government deficits is because we continue to cast them in such a negative light.

Fiscal deficits are going to be with us. They’re not going away. And we shouldn’t want them to. Decrying them will only undermine the democratic agenda.

I'm a huge fan Dr.Kelton ,an 88 yr old average Joe.or Ron, and attracted to MMT primarily because it makes "common sense" to me and not from any study of economics. Other things that make common sense is Medicare for all and for me ALMOST as important, is a Government Guaranteed Job Program with a living wage and benefits.I hear a lot of discussion about National Health and almost nothing about the GGJP. Would appreciate you addressing GGJP in a future post if you would please--many thanks-keep up the great work !! Average Ron

I'm a big fan of your work; keep it up. That said, I don't think that you do justice to your perspective with your G-T analysis. Bond purchase removes money from the economy. In fact, it removes an amount closely correlated with G-T. Deficits are not necessarily inflationary; whether they are financed by borrowing or printing makes all the difference.

Keep up the great work, Art Williams