As I watch—and participate in—the great inflation debate, I find myself thinking back to my time as an undergraduate, studying intermediate microeconomics with Professor John F. Henry.

Henry was masterful in the classroom, and he’s the reason I decided to pursue my graduate studies in economics. His exams were legendary. I only had one other professor—a finance prof—who could write a multiple-choice exam that actually required some hard thinking. To do well, you had to be able to recognize when a question had more than one right answer. A typical exam included dozens of questions that looked like this:

Question: __________________________________

a.) possible answer

b.) possible answer

c.) possible answer

d.) possible answer

e.) a & b

f.) a & c

g.) a & d

h.) b & c

i.) b & d

j.) c & d

k.) a, b & c

l.) a, b & d

m.) a, c & d

n.) b, c & d

o.) All of the above

p.) None of the above

I don’t give my own students multiple-choice exams, but I’ve been thinking about how I’d construct a John Henry-inspired question about inflation and why it’s running at its hottest pace in 40 years. I’m pretty sure I could come up with twenty-five possible answers: a.) — y.) But the correct response would be z.) All of the Above.

That doesn’t mean that everything matters or that everything that matters is equally important in terms of explaining what brought us to where we are today. But it does mean—or at least it should mean—that things are a lot more complicated than what many commentators would have us believe.

Take, for example, this recent New York Times column by former US Treasury official Steve Rattner. After calling President Biden’s inflation story “misleading” and overly “simplistic,” Rattner offered his own simplistic take. “It’s a classic economic case of ‘too much money chasing too few goods’.” Whereas Biden emphasized the too few goods part of the story, saying, “The reason for the inflation is the supply chains were cut off,” Rattner declared it a too much money problem, blaming Congress for dishing out too much cash to too many people. Rattner doesn’t deny that the pandemic put some kinks in the global supply-chain, but he argues that “the bulk of our supply problems are the product of an overstimulated economy.” Since fiscal deficits are the main villain in his inflation story, Rattner ends his piece by calling on the Biden administration to “make deficit reduction” an urgent priority.

Rattner isn’t alone. Larry Summers and Jason Furman have a similar diagnosis, although they’re primarily calling for monetary tightening (i.e. interest rate hikes) rather than urging Democrats to raise taxes and slash government spending to bring down inflation. Like Rattner, Summers and Furman have attributed the run-up in inflation to excessive stimulus, especially from the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) passed by Congress last March. That’s the package that re-upped federal unemployment assistance, sent out those $1,400 checks, and delivered monthly cash assistance to families with kids under the age of 18 (child tax credit). While admitting that pandemic-induced disruptions were also a factor, Summers doubts we’d have inflation running this hot “without the overwhelming stimulus that was applied well into the recovery.” Even progressive economists, like Dean Baker, who tend to focus on the upside of doing several large fiscal packages, concede that “the current inflation rate would almost certainly be lower” if Congress hadn’t passed the ARPA last March.

But how much lower?

Furman says he believes that “90 percent of inflation is the result of excess demand driven by fiscal and monetary policy.” It’s not that he dismisses supply-chain disruptions, bottlenecks in shipping and trucking, or even the massive shift in consumer demand that aggravated these logjams. It’s just that he attributes most of our supply-side woes to excessive demand-side stimulus—a too much money problem.

That’s not what researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found back in October, nor is it consistent with what Mark Zandi and his team at Moody’s Analytics published just last week.

Here’s the gist of what economists at the San Francisco Fed found:

“In an effort to stabilize the U.S. economy through the severe disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress passed a series of packages amounting to the largest macroeconomic fiscal relief since the New Deal of the 1930s. Beginning with the $2.2 trillion CARES Act in March 2020 and followed by $900 billion of additional relief in December, the relief effort continued into 2021 with the passing of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP) this past March.

By the time the ARP was passed, the economy had at least partially recovered from the pandemic. The later timing and large size of the ARP stirred debate about whether it is causing an overheating of the economy and fueling a sustained increase in inflation…[as] For example, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers stated…

Our analysis suggests that the ARP is projected to cause a transitory increase in the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio, which translates into a core inflation rate that is about 0.3 percentage point higher per year through 2022.”

In other words, the much-maligned $1.9 trillion fiscal package that supposedly got us into this mess is barely adding to inflation. Mark Zandi agrees:

The analysis by Moody’s Analytics is interesting, because it attempts to answer the question that Dean Baker alluded to above. Namely, what kind of inflation rate would we be dealing with if we hadn’t gotten such robust stimulus? Zandi and his team arrive at an answer by constructing a “counterfactual scenario in which governments in the world’s 10 largest economies—accounting for more than two-thirds of global GDP—do not provide economic support to households and businesses during the pandemic.”

Here are some of the key takeaways:

“Arguably the most controversial of the U.S. fiscal support packages was the nearly $2 trillion American Rescue Plan that became law in March 2021. The ARP has been criticized as being too large, overstimulating an already fast-improving economy and significantly contributing to the currently uncomfortably high inflation.

This perspective is not consistent with our results…

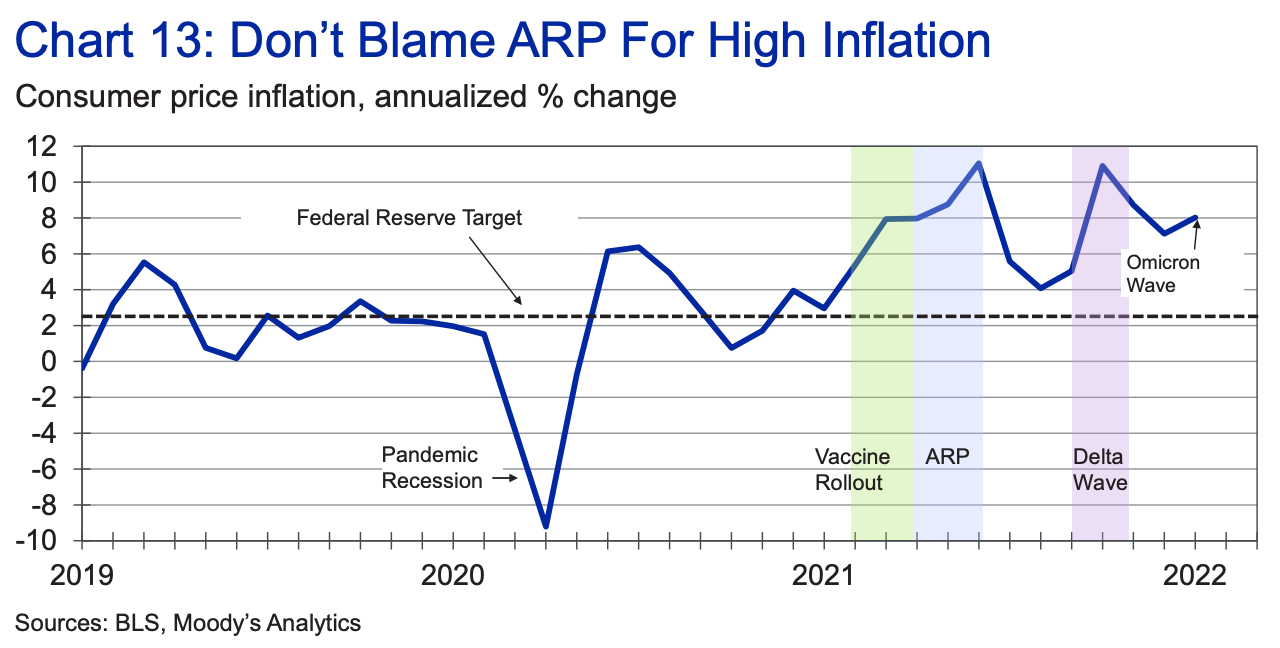

The ARP has contributed to the acceleration in inflation by supporting increased consumer demand, but this occurred almost entirely in the first half of 2021 when higher inflation was not considered a problem (see Chart 13).

Inflation only became uncomfortably high when the Delta wave of the pandemic hit in late summer last year. This inflation was a surprise, but so too was the Delta variant, as it came immediately on the heels of the vaccine rollout and widespread optimism that the pandemic was more-or-less behind us. Delta slammed consumer demand, as it prompted renewed self-quarantining and border restrictions, which by itself would moderate inflation, but it also severely disrupted supply. Global supply chains were badly scrambled, as this wave of the pandemic was especially hard on Southeast Asia, which was lightly vaccinated at the time, and where most supply chains begin.”

Taking all of this into consideration, the report finds that the hotly-contested $1.9 trillion package is responsible for adding just 0.35 percent points to inflation.

Since there is evidence that the ARP is part of the reason—albeit a very small part—that inflation is currently running at a 40-year high, I would include it on my Henry-inspired multiple-choice exam. But I would make sure that my students understood why it was technically (and trivially) a correct response.

What else belongs on the list?

Lots of things! The virus itself. Energy/oil cartels. A faster-than-expected recovery. Semiconductors/chip shortages. Just-in-time production. Extreme offshoring. A privatized and deregulated logistics system. The shift in consumer spending from services to (durable) goods. Consolidation in trucking/meatpacking/rail. The Ocean Shipping Reform Act (1998). Trucker shortages. Decades of dis/underinvestment in transportation/infrastructure/etc. Lingering impacts from the 2007/08 financial crisis. Climate/weather. Lack of housing inventory. Extreme efficiency/just-in-time production. The unbridled pursuit of maximum shareholder value. Tighter labor markets/rising wages. And yes, opportunistic price increases—i.e. price gouging/profiteering.

To anyone who’s been paying attention, that last one is patently obvious. Reasonable people can debate the extent to which companies are taking advantage of the current inflationary environment to raise prices in excess of any mounting cost pressures they’re facing, but only an ideologue would claim it plays no role whatsoever. As Paul Krugman recently put it:

“Nobody sensible would argue that opportunistic exploitation of market power is the main factor behind recent inflation. But contrary to what some people might want you to believe, economic theory by no means rules out the possibility that it may be a factor.”

For some reason, Larry Summers was incensed by Krugman’s column. Perhaps it was because Krugman credited Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) for taking the issue seriously. After “sleeping on it,” Summers fired off this thread, effectively dismissing the argument that price-gouging is one of the reasons consumers are paying higher prices.

I would have no problem including “opportunistic price increases” as one of the many correct answers on my hypothetical exam. There is sufficient—and mounting—evidence to substantiate the claim. In addition to The American Prospect’s incredible February issue, here’s an excerpt from an outstanding piece by Jeanna Smialek of The New York Times, published earlier today.

“Companies are taking advantage of a moment of hot and seemingly unshakable demand — one in which consumers are spending ‘with a vengeance,’ to borrow the words of one executive — to cover rising costs and to expand their profit margins to prepandemic or even record levels. Corporate executives have spent recent earnings calls bragging about their newfound power to raise prices, often predicting that it will last.”

The point is, when it comes to explaining our current bout of high inflation, there’s no dearth of right answers. There are many forces at work. To bring inflation back down, we need more than a catalogue of everything that matters. As I keep saying, the policy response to fighting inflation should be tailored to the diagnosis. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the inflation problem.

There are things we can do to enhance price stability in the short-term—getting past the pandemic, eliminating non-strategic tariffs, unclogging ports, licensing more truck drivers, negotiating prescription drug costs and moving to Medicare for All, to name just a few. Longer term—by which I mean years, not decades—we need to restore domestic manufacturing capacity and move away from fossil fuels. We need to build millions of units of affordable and sustainable housing and invest heavily in mass transit. We must start now.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has just released a major new scientific report, written by 270 researchers from 67 different countries. The closing paragraph of the report’s summary reads:

"The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all."

Rattner’s call for fiscal austerity makes no sense on the merits. It is economically, politically, and literally suicidal. But neither do calls for aggressive interest rate hikes, which are premised on a wrong-headed diagnosis of an “overheating” economy. What we have is an overheating planet. What we need is a massive, globally-coordinated Green New Deal.

It's astonishing that no one wants to touch price controls as the answer to this problem. This reminds me of the joke of two inmates in a prison cell. One guy wants to hang a picture on the wall, but he's trying to bang the POINTED end of the nail into the wall with no success. He's slams down his hammer in disgust and declares: "These idiot prison guards can't even give you nails with the point on the right end!" His cell mate points to the opposite wall and says: "You idiot! Don't you know that nail is meant to go on THAT wall?" Neither man can see the obvious solution to the problem.

Think of the pandemic this way: suppose New York City is blasted by a rogue cold front and temperatures plunge into the single digits in the middle of July. What should New Yorkers do? Curse the cold and stay indoors, stop going to work and curtailing their shopping trips and restaurant visits, or should they get their winter coats and sweaters out of storage and weather out the deep freeze? Yes, it's weird to wear a winter coat during a New York summer, and it's weird to slap on price controls--except in the middle of a pandemic. You do what the circumstances require.

Thoughtful article. Keep the data flowing