Why Are Democrats Bragging About Plunging the Private Sector into Deficit?

Democrats want to keep shrinking the deficit to fight inflation but also keep the economy out of recession. Good luck with that.

Last week, I happened to catch an interview with one of President Biden’s economic advisors, Jared Bernstein, on CNBC’s Squawk Box. The interview mostly focused on this recently-released White House statement about economic recessions—whether we’re currently in one, ambling toward one, or well-positioned to avoid one—but it veered into strange territory when one of show’s hosts asked Bernstein why he and others in the administration don’t do more to “call out” members of the democratic party who are “too far left.”

Bernstein’s response was interesting.

Instead of leaning into one of the high-profile debates over so-called “woke” politics, Jared offered an example of an area of disagreement where the administration is actively pushing back against party outliers—deficit reduction.

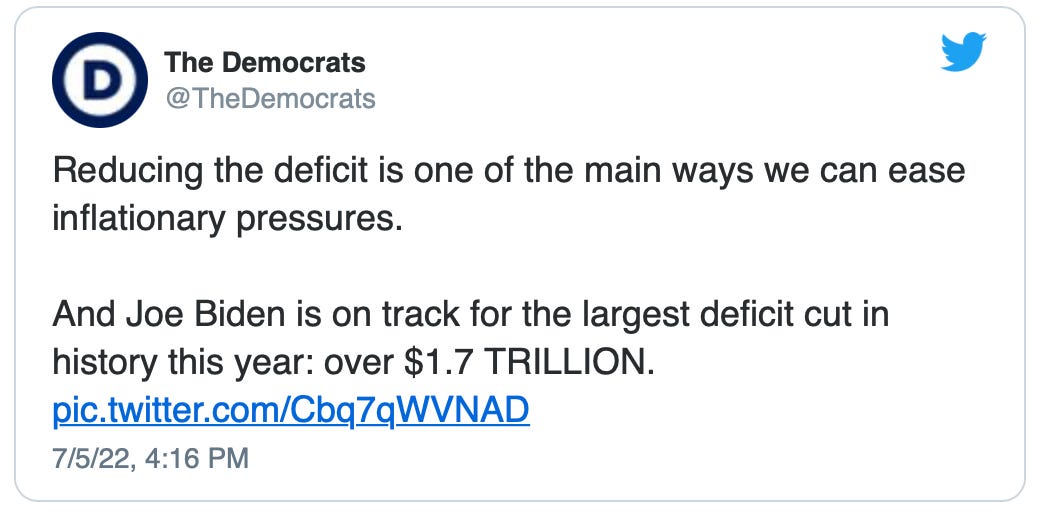

He touted a 77 percent drop in the deficit—$1.7 trillion—in the current fiscal year, adding that the White House is aiming for even bigger deficit reduction, against the advice of some economists within the party. I’m not going to speculate about which economist(s) he had in mind, and it shouldn’t matter. While I remain critical of the administration’s focus on deficit reduction, my view is that this is not—or should not be—a question of one’s political ideology.

To see why I think Democrats are barking up the wrong tree by bragging about the historic drop in the deficit, let’s look at the issue through the apolitical lens of the sector financial balances.

The Sector Financial Balances

The sector financial balances (SFB) are integral to MMT. The framework was popularized by Wynne Godley, a perennial outsider who was once the head of the Department of Applied Economics at Cambridge University. After correctly anticipating the crash in the British pound in 1992, Godley was appointed to a group known as the “six wise men” advising the UK Treasury. He ended his long career in the United States, working as a Distinguished Scholar at the Levy Economics Institute, where he turned his attention to analyzing the US economy. I was fortunate to have been at the Levy Institute for part of that time and to have Godley as a member of my doctoral dissertation committee.

Godley built his economic models around the idea that the economy could be modeled as a system of interlocking balance sheets. In order to tell a complete and coherent story about the economy, he believed that it was important to account for the flow of payments across all sectors (and the accumulation of those flows into stocks of financial assets).

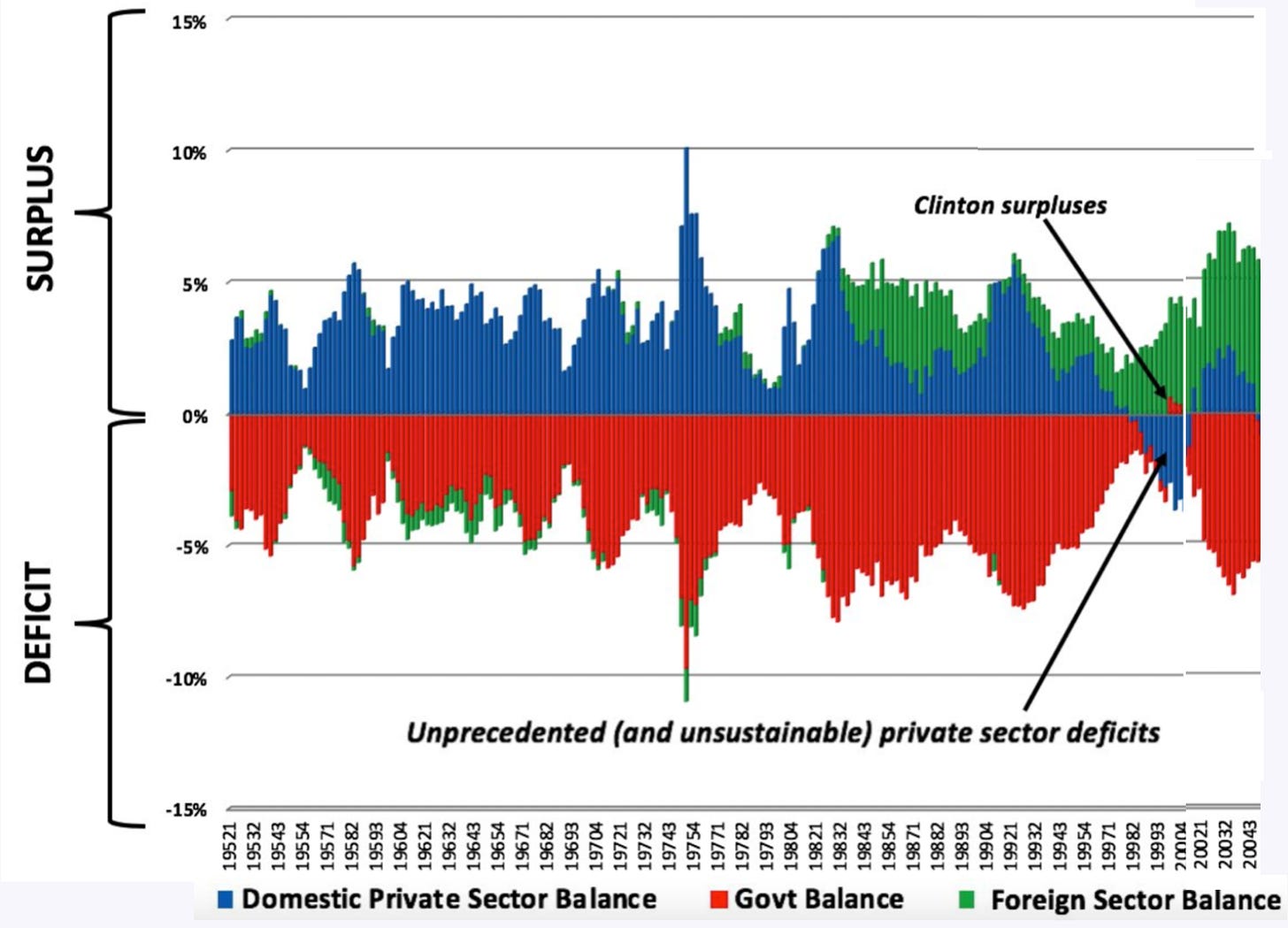

Looking at the economy through the lens of a stock-flow consistent model frequently allowed Godley to anticipate problems that others were missing. For example, when democrats and republicans were celebrating the emerging fiscal surpluses in the late 1990s and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was predicting surpluses as far as they eye could see, Godley was pointing to the concomitant deterioration in the private sector’s financial position and challenging the coherence of the CBO forecast.

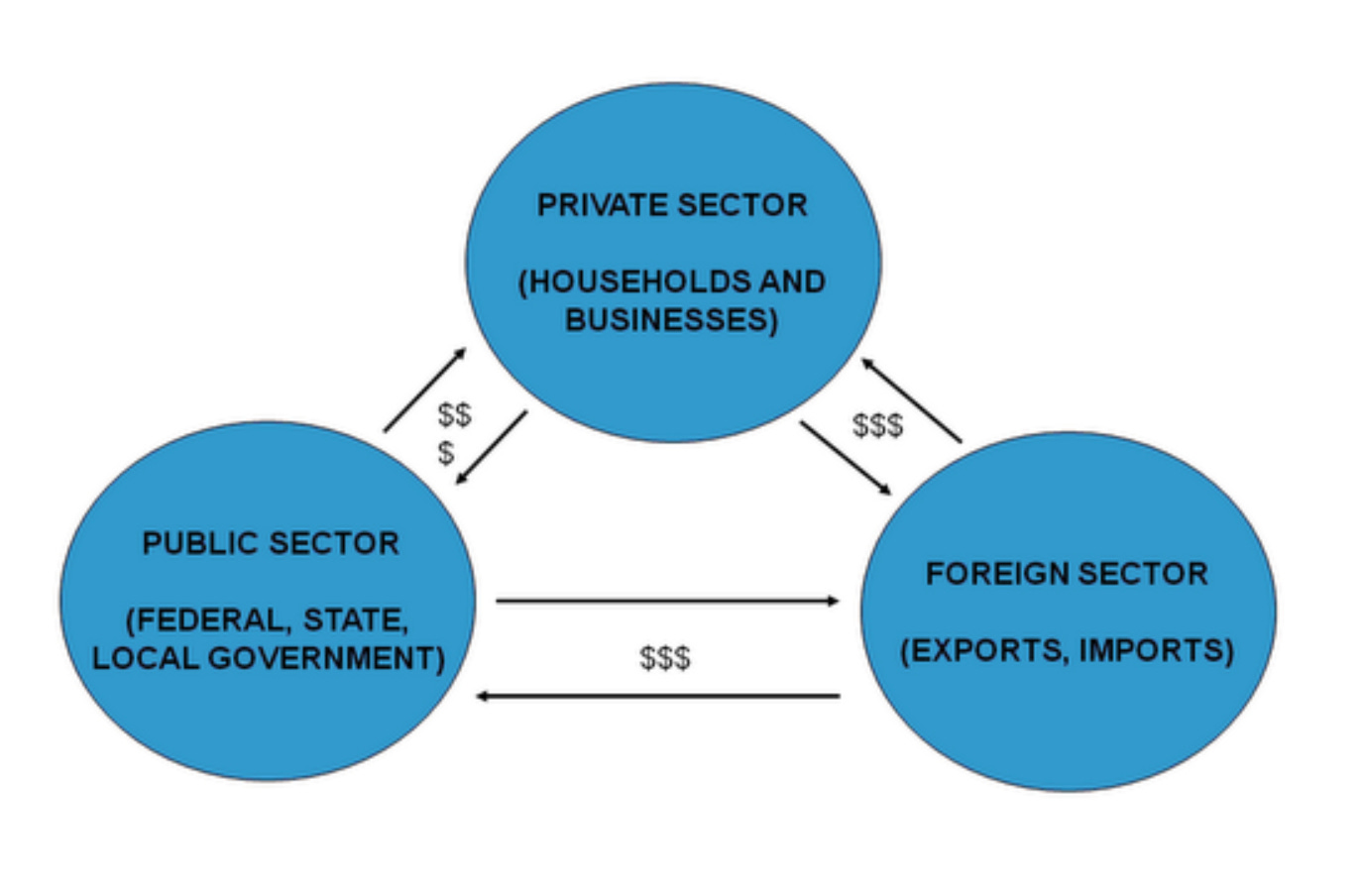

The simplest way to understand Godley’s model is to think of the economy as a set of puzzle pieces that fit perfectly together. Let’s start by looking at three big pieces. Each piece represents a distinct “sector” of the economy.

The US private sector

The US government sector

The foreign sector

Over any discrete period of time, each sector will either experience a net inflow of financial payments—i.e. a financial surplus achieved by spending less than its income—or a net outflow—i.e. a financial deficit incurred by spending more than its income. As Godley used to say to me, “every payment must come from somewhere, and every payment must go somewhere.”

Accounting for both the “to” and “from” is what ensures that everything nets to zero in the end. Because a surplus in one sector can only be achieved via a deficit in at least one other sector. Just as every country on earth can’t simultaneously achieve a trade surplus (or deficit), each of our three sectors can’t be in surplus (or deficit) at the same time.

An advantage of of using the SFB model of aggregate demand is that it is derived from an accounting identity that can be found in virtually any macroeconomics textbook.

(Private Saving – Investment) = (Government Spending – Taxation) + (Exports – Imports)1

or

(S — I) = (G — T) + (X — M)

The figure below, which comes from MMT economist Scott Fullwiler, helps to visualize Godley’s three-sector model. To understand what’s going on, think of it this way. Suppose you have a stopwatch and you hit the button to start the timer. From the moment you begin keeping track, dollar-denominated financial assets are changing hands. When we stop the clock, we can account for the net payments to see which sector(s) experienced net inflows (surpluses) and which ended up with net outflows (deficits) during that discrete interval of time.

We refer to the left-hand side of the equation above (S-I) as “private sector net saving.” When the term is positive, it means that the private sector is net saving—i.e. running a surplus and adding to its net financial wealth. When the term is negative, it means that the private sector is net borrowing—i.e. running a deficit and subtracting from its net financial wealth.

Godley made two important observations using this framework. First, the domestic private sector—i.e. all of the households and businesses in the US economy—typically finds itself in a surplus position, both because it normally prefers to spend less than its income and because periods of rising private sector indebtedness tend to end badly. In other words, deficits for the private sector tend to be rare and short-lived.

If you’re accustomed to using the MMT lens, then you probably understand why Godley felt the way he did about private sector deficits. Whereas a currency-issuing government doesn’t need to worry about accumulating net financial assets to stay afloat, currency-users do. The problem is that the private sector cannot be the source of its own net financial surplus.

A commercial bank (within the private sector) can lend to a household or to a private business, and that loan will give rise to a newly-created bank deposit that increases the money supply (M1). But the loan exists as both an asset (on the bank’s balance sheet) and a liability (on the borrower’s balance sheet). Similarly, the deposit exists as both a liability (on the bank’s balance sheet) and an asset (on the borrower’s balance sheet). Since everything “cancels out,” no net financial assets have been created.

In order to acquire net financial assets—i.e. to achieve a financial surplus—the US private sector (as a whole) must receive net financial payments from “outside” itself. Theoretically, the private sector could build its surplus by drawing net inflows from the government sector or the foreign sector (or a combination of the two). Practically, however, there is only one game in town—government deficits.

That’s because the US runs persistent current account deficits with the rest of the world. That, by definition, means that our trading partners end up with current account surpluses (shown in green below). For many decades, America’s trade deficit has widened, narrowed, and widened again. It sometimes shrinks, but it never disappears. And it’s not likely to go away anytime soon. The US has been running current account deficits for generations. Until that changes, there is only one way to keep the US private sector out of deficit—the government must run a deficit that is bigger than the US current account deficit.

Private Sector Financial Surpluses Mitigate Recession Risk

The SFB framework is derived from an accounting identity, but it is useful beyond merely presenting historical data in a stock-flow consistent manner. Godley made a career out of using the framework to make projections about how the economy might evolve over time. Others, including Goldman Sachs’ chief economist Jan Hatzius, have done the same. Here’s Hatzius:

I’ve long been fascinated with looking at private sector financial balances in particular. There was an economics professor at Cambridge University called Wynne Godley who passed away a couple of years ago, who basically used this type of framework to look at business cycles in the U.K. and also in the U.S. for many, many years, so we just started reading some of his material in the late 1990s, and I found it to be a pretty useful way of thinking about the world.

It’s usually not something that gives you the secret sauce at getting it all right, because there are a lot of uncertain inputs that go into this analytical framework, but I do think it’s a reasonable organizing framework for thinking about the short to medium term ups and downs of the business cycle.

Basically, in order to have above-trend growth – a cyclically strong economy – you need to have some sector that wants to reduce its financial surplus or run a larger deficit in order to provide that sort of cyclical boost, most of the time.

It’s such an important point, and one that I think most economists (not to mention most policymakers) simply don’t understand. Let me state it again: to maintain a strong economy, at least one sector needs to be willing and able to consistently spend more than its income.

Here’s the problem.

In the United States, that “someone” is almost always going to have to be the federal government. And yet no one seems to get it!

Last Monday, Jared Bernstein was bragging about the historic collapse in the government deficit. On Wednesday, we learned that Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) reached agreement on a plan to shrink the deficit by more than $300 billion. And on Thursday, Janet Yellen held a news conference where she proclaimed that “We’re in a period where there’s very significant fiscal drag.” All while the administration tries to downplay the risk of recession.

Godley, who was always tugging on his wispy white hair, would surely be pulling it out by the handful if he were alive to see it. Back in the 1990s, he was nearly alone in pointing out that the government’s financial balance had swung too far in the wrong direction. As Warren Mosler sometimes puts it, the government deficit needs to be big enough to support the private sector’s credit structure. If you read Hatzius’ note to investors, you’ll find that he’s making exactly the same point.

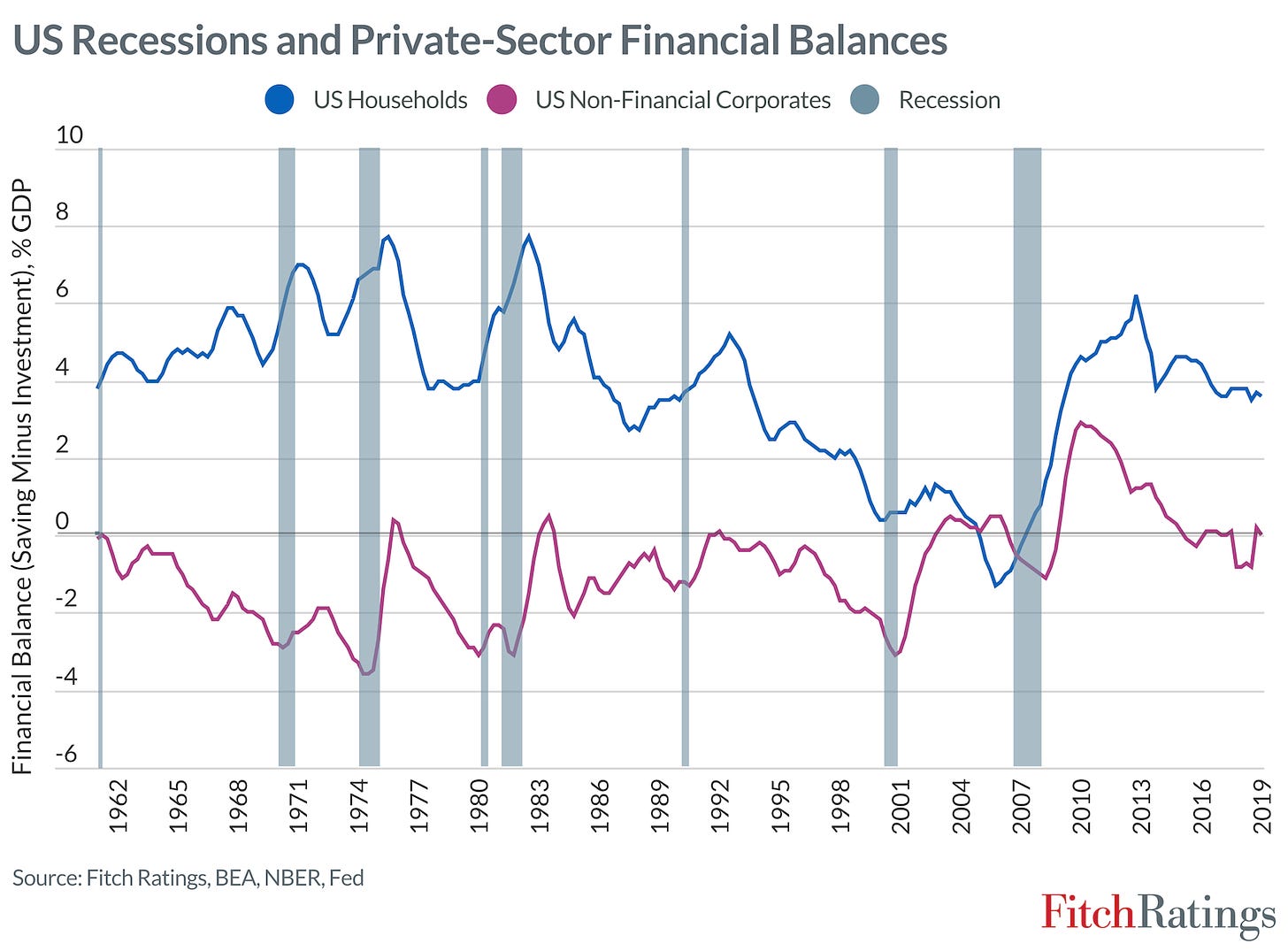

And if you read this short but very good (pre-pandemic) post from Fitch Ratings, you’ll understand how to think about recession risk in the context of the SFB framework. Here’s an excerpt:

Most post-war US recessions have been preceded by deteriorating private-sector financial imbalances…

The length of the current expansion in US GDP has generated significant market commentary about the growing risk of an imminent US recession…

The run-up to previous US recessions typically has seen either the corporate sector or the household sector moving into a substantial financial deficit.

As we often do in MMT, Fitch disaggregated the private sector into Households (blue) and non-financial corporations (red). The point they’re making—and it’s a point MMT economists have made for decades—is that recessions tend to be preceded by a deterioration in the private sector’s financial position.

The chart shows that recessions in the late 1960s, early 1980s and in 2001 were preceded by a significant deterioration in non-financial corporate sector finances, while the 2008 recession was preceded by the household sector moving into a hitherto unprecedented deficit.

So where are we today?

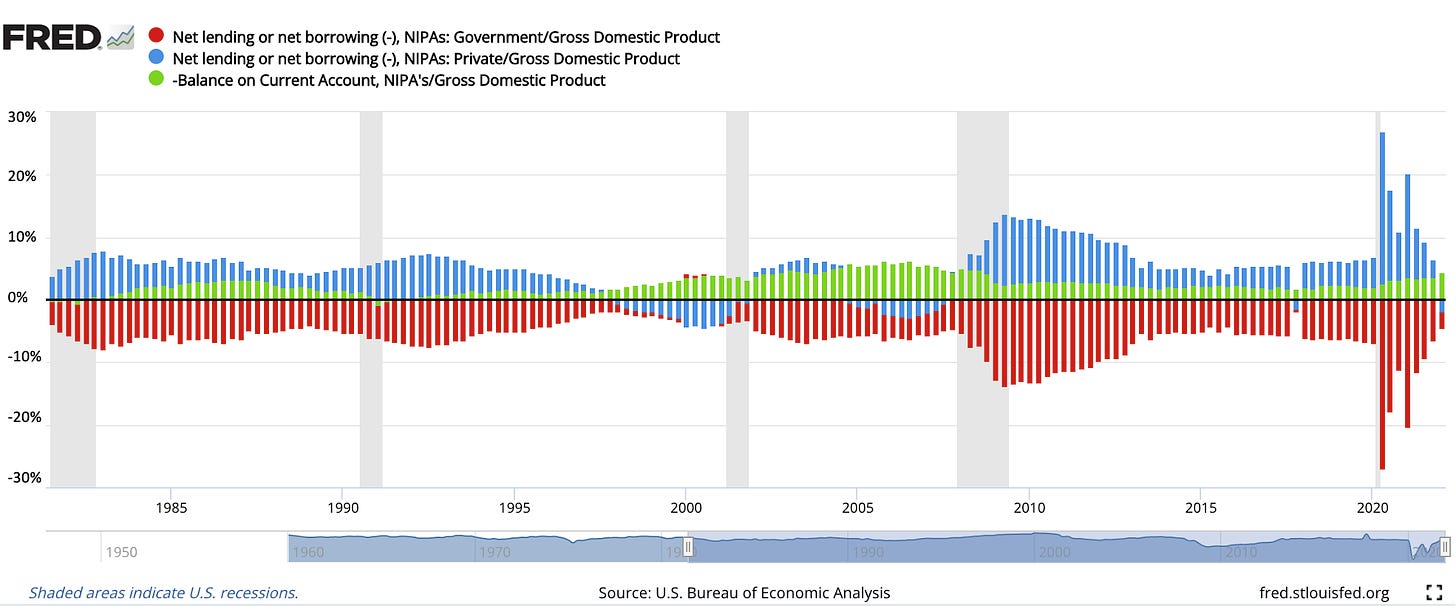

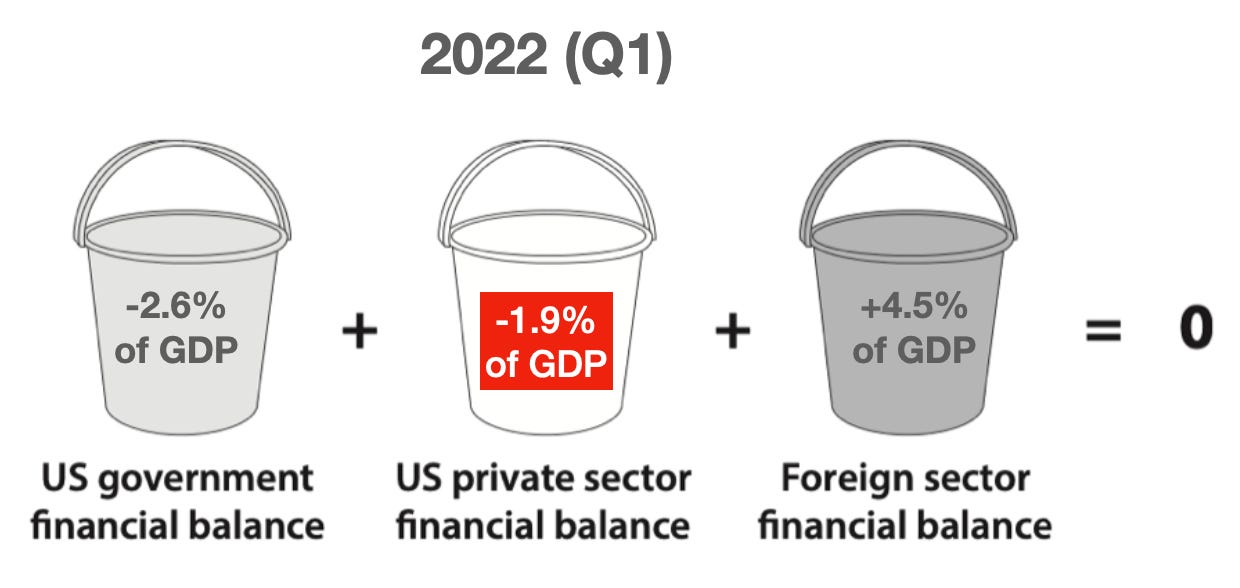

If you squint, you’ll find that the US private sector slipped into deficit in the first quarter of 2022. If you don’t want to squint, you can click to enlarge the image. I want to focus on just how quickly the private sector’s financial position has deteriorated.

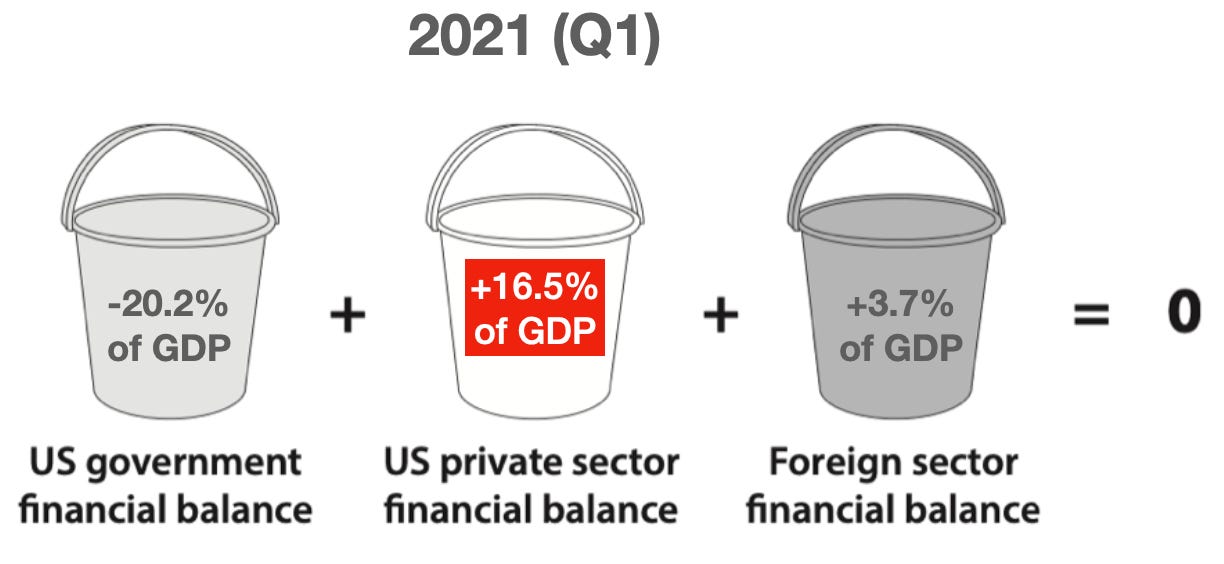

At the start of 2021, the balances across the three sectors looked like this.

The government sector as a whole (federal/state/local) was deeply in deficit, and the US private sector (as a whole) carried a whopping financial surplus equal to 16.5 percent of GDP. Those weren’t historically “normal” figures. They were boosted by pandemic-induced changes in desired saving patterns coupled with trillions in fiscal support for households and businesses.

But look what’s happened over the course of the last year. In the first quarter of 2022, the government deficit was no longer big enough to keep the private sector in surplus. Some of the collapse in the government deficit happened organically, since the government’s financial balance tends to be procyclical—i.e. tax receipts climb during expansions and fall off when the economy slows or enters a recession. But most of it was the result of the massive withdrawal of fiscal support as pandemic spending programs wound down in 2021.

Admittedly, we’re only looking at the first quarter of 2022 data, but we can use the SFB framework the way Godley, Hatzius, and Fitch would to think about the implications of further deficit reduction in the years ahead. According to the White House, we are already on track to see the federal government’s deficit drop by $1.7 trillion this fiscal year. And if the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 manages to pass in its current form, then even more fiscal tightening will be put in place.

You can argue—as President Biden and many democrats are doing—that cutting the deficit will help to bring down inflation. But you would be hard-pressed to argue that it can be done without adversely impacting the private sector’s financial position.

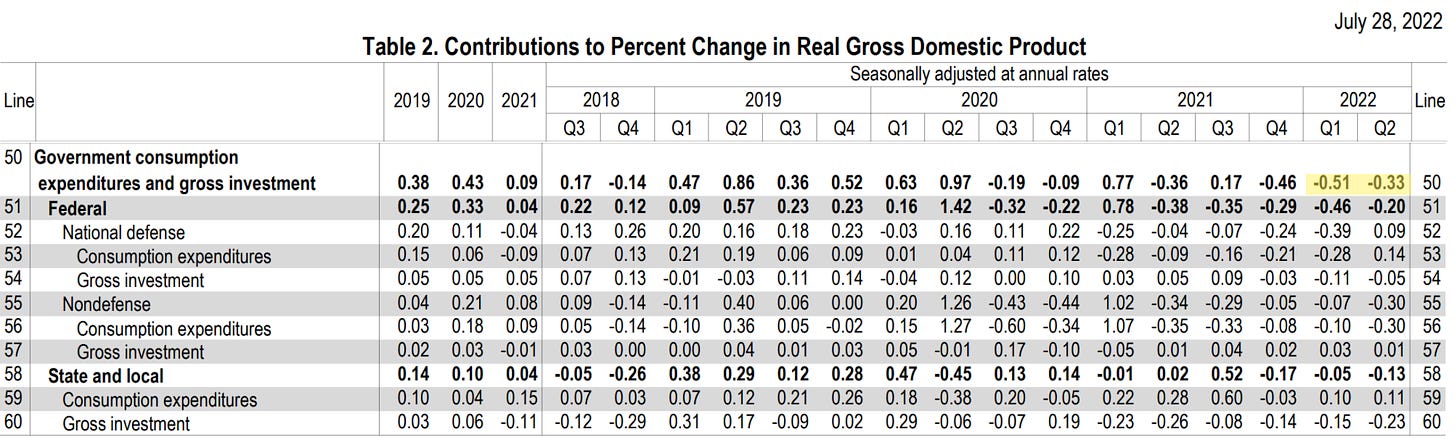

We have already seen two consecutive quarters of declining real GDP. And one-third of the most recent contraction was driven by a fall in government spending.

Democrats (and political pundits) can brag about the rapid decline in the government deficit and even embrace further deficit reduction to fight inflation, but they shouldn’t do so without contemplating the risks of plunging the the private sector into deficit.

To be precise, we would use the current account balance instead of the trade balance. For some countries, the difference can be important. For the US, it is typically less significant so we sometimes present the SFB equation in its simplified form. The complete version of the model can be written:

Private Sector Surplus or Net Saving = Government Deficit + Current Account Balance

"The problem is that the private sector cannot be the source of its own net financial surplus." For me, this is the startling, slap-upside-the-head insight of MMT! When the next so-called econ expert appears on TV, I'm hoping for the following exchange:

"So it's your opinion as a member of the Council of Economic Advisers that the gov't should be paying down our national debt."

"The gov't has to balance its books just the way every American household must. So, yes."

"Tell me, do you have U.S. dollars in a checking or savings account--or stuffed in your mattress--that you own free and clear?"

"Yes, of course I do--I mean, not in my mattress...."

"So you don't have any outstanding bank loans?"

"Well, I have a mortgage, but the equity in my house would take care of any default."

"And you haven't robbed a bank lately?"

"I'm an economist, not a thief!"

"OK...so where did those dollars come from?"

"What do you mean? I earned them."

"Well, yeah, but if you didn't rob a bank and you don't have an outstanding bank loan, then those dollars can't be "bank money."

"No, it's my money!"

"You're not a counterfeiter, are you?"

"Certainly not!"

"Good. Here's my point. Banks create money when they issue loans. But banks have a nasty habit of wanting to get paid back in full--plus interest. So all of the "bank money" circulating throughout the economy is spoken for. Every loan is simultaneously an asset and a liability for both the bank and the borrower. The whole shooting match sums to zero. There's no way you can own "bank money" free and clear."

'Well, yes, I suppose that's true."

"And I assume you didn't go in your backyard and pick the fruit off your Benjamin Tree?"

"Look, we all know, hopefully, that U.S. dollars don't grow on trees."

"Exactly. So where did your U.S. dollars come from? I see you look a bit flustered, so let me continue. Unlike a bank, which must follow strict rules or lose its charter, the federal gov't not only issues our currency but doesn't actually care about being repaid in full. That's why the pre-pandemic "national debt" was about $28 trillion! And guess what? It was one of the greatest achievements in the annals of human history. The U.S. Treasury/Federal Reserve had been able to pump $28 trillion in deficit spending (most of it since WWII) into the world economy while keeping interest rates and inflation rates absurdly low. And that's where the U.S. dollars in your personal bank account came from--federal deficit spending. And look, the money itself is no big deal. But just as banks have a nasty habit of wanting to get repaid, workers have a nasty habit of wanting to be paid for their work. And injecting this much currency into the economy (the pre-pandemic inflation rate told us it wasn't TOO MUCH) allowed our economy to reap the benefits of incredible innovation and worker productivity. And it made millions of Americans more financially secure, including you."

"OK, OK, you make valid points. But look at inflation now! Haven't the national debt chickens come home to roost?"

"There you go, again. We'll talk about that next time. But for now, just remember where the U.S. dollars for those "Hamilton" tickets you bought last month came from."

Kelton you so totally rock! I prefer prefer the Godly answer for tax understanding, “Give back to Caesar what belongs to Caesar....”. Thanks all you smart people. Keep the Faith and an open mind.