I’ve written quite a lot about Social Security over the years. Of course, I come at it from an MMT perspective, which means that I have never worried about the program’s “solvency” the way many other economists do. The fullest expression of my views can be found in chapter 6 of my book, The Deficit Myth, but this Twitter thread provides a decent summary.

When it comes to programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, there’s an obsession—not shared by MMT economists—with “program solvency.” It’s always about how much money one expects to bring in—mostly in the form of payroll taxes—relative to how much one expects the government to pay out in the form of benefits. When anticipated revenues fall short of anticipated payouts, nearly everyone frets about looming “shortfalls” and program “solvency.”

Shortfalls spell trouble, or so we are told.

If you look at the latest report from the Trustees of the Social Security Administration, you’ll find out where the supposed troubles lie. According to the Trustees, Social Security’s financial woes are currently confined to the Old-Age and Survivor’s Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which is projected to be depleted in 2034. After that point, unless something is done to address the revenue shortfall, the program can cover only 77 percent of promised benefits. The Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund is considered “solvent” for at least the next 75 years, so no “trouble” there at the moment.1 Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, which pays for hospital services like inpatient care, is expected to face trouble later this decade. Specifically, the Trustees project that the HI Trust Fund will be exhausted in 2028, after which point there will only be enough new revenue to cover 90 percent of anticipated benefits. And then there’s the outlier . . . the Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund. This one includes the prescription drug plan (Medicare Part D) from the George W. Bush era. Unlike all of the other programs, the Trustees tell us that SMI “is adequately financed into the indefinite future because current law provides financing from general revenues” to ensure that any unaddressed “shortfalls” cannot force benefit cuts.

Say what?

This program isn’t just good for the next 75 years, it’s good indefinitely! But how? Easy. It’s because Congress—a legislative body—bestowed special legislative language on this particular part of Medicare.

As the great Northwestern University economist Robert Eisner explained almost a quarter-century ago, Congress could always bestow the same legislative language on Social Security’s trust funds or even dispense with the trust funds altogether. They are, after all, “merely accounting entities.” Instead of fretting over arbitrary numbers on a ledger, Eisner wanted people to understand that “Social Security faces no crisis now or in the future.” It cannot “go bankrupt.” It will be there as long as those who seek to undermine it don’t get their political way.

Ironically, it’s the same point made here by MMT economist Alan Greenspan (wink). Okay, we don’t claim Greenspan as one of our own, but he does get this one right. And, more importantly, he gets it right for the right reasons. It’s as if those are MMT lenses he’s wearing!

Listen to him explain to former Congressman Paul Ryan (R-WI) why his obsession with “system solvency” isn’t the right thing to worry about when you’re thinking about the spending capacity of a government that issues a non-convertible (floating exchange rate) currency. [click to play]

Greenspan was being somewhat polite when he said, “the cash itself is nice to have.” He knows that the trust funds are just an accounting construct and that the government doesn’t need to maintain a stockpile of dollars in order to meet its obligation to future retirees, their dependents, and the disabled. From the look on Congressman Ryan’s face, I’d say he knew it too.

It’s a shame more people don’t understand that the entire debate over “solvency” is rooted in a flawed understanding of our monetary system and the mechanics of government finance.

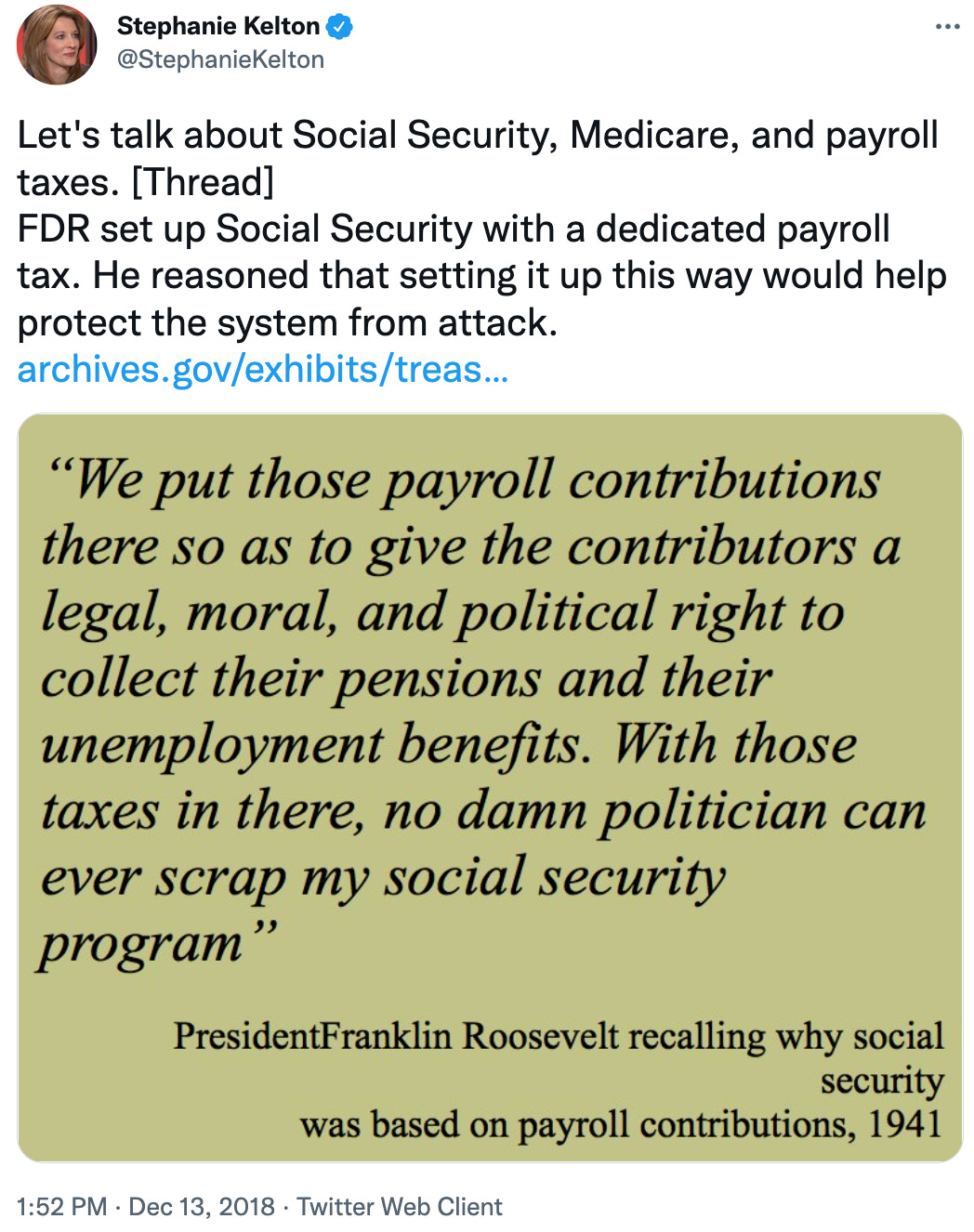

As I explain in this thread, much of the confusion stems from the way President Roosevelt set up Social Security in 1935.

I have seen that quote many times—and I use it in my book—but I didn’t realize until this morning that it actually comes from this memo, written by Luther Gulick in 1941.

I also didn’t know that some of FDR’s advisors had challenged him on the decision to tie benefits to the payroll tax or that Marriner Eccles, who served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve, urged the Roosevelt administration to abandon its push to expand Social Security benefits during WWII. And I’d never seen anyone reproduce the last sentence from Gulick’s memo:

I suggested that it had been a mistake to levy these taxes in the 1930’s when the social security program was orgiginally [sic] adopted. FDR said, “I guess you’re right on the economics. They are politics all the way through. We put those pay roll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program. Those taxes aren’t a matter of economics, they’re straight politics.”

I got to thinking about all of this again after learning that Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) recently introduced the Social Security Expansion Act, which aims to make Social Security “solvent for the next 75 years.”

I’ll have more to say on all of this tomorrow.

When people talk about Social Security, they’re usually referring the hypothetical combination of Old-Age Survivors and Disability Insurance (OASDI), although they are separate entities under law.

I have to disagree with your take on Paul Ryan's expression. He had no clue what Alan Greenspan said, and was trying to cover that up to protect his "financial-adult-in-the-room" persona which was his stock in trade.

I await your discussion of Sen. Sanders' Social Security Expansion Act with considerable trepidation.

The summary to which you link suggests that Sanders believes the Federal government must amass funds through taxation (here, payroll taxes on a higher share of income for high-paid salary earners) before it can spend (on Old Age Survivors). Clearly, from an MMT perspective we believe this to be incorrect. Tax the rich for greater social equality? Yes! But tax the rich to restore Social Security's "solvency"? That's letting Lindsay Graham and his ilk define the field of battle.