In my last post, I wrote about growing concern that the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes could trigger a financial accident that spills over into financial markets. With yesterday’s award in honor of Alfred Nobel, I found myself thinking a lot about Hyman Minsky.

Minsky is the guy everyone rediscovers whenever something really bad happens—i.e. when something “breaks”— in financial markets. My friend Paul McCulley coined the phrase “Minsky Moment” to reference the breaking point.

If you haven’t heard much about Minsky before, here’s one of his former students, MMT economist and author of the book Why Minsky Matters, L. Randall Wray with a 5-minute “crash course.”

Minsky is best-known for his 1986 book, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, and for developing his Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH).

The Financial Instability Hypothesis

Minsky rejected the classical description of the economy— from Adam Smith or Léon Walras—which holds that “the economy can best be understood by assuming that it is constantly an equilibrium seeking and sustaining system.” For Minsky, as for Keynes, capitalist economies are inherently unstable. You might get a stretch of relative tranquility, but every so often, something breaks. “Stability is destabilizing,” as Minsky liked to say.

Instead of self-correcting forces moving the system back to a stylized equilibrium, a negative impulse can begin to feed on itself, moving the economy further and further away from anything resembling an ideal state. In the extreme, you can get distress selling and a collapse of asset prices. A debt deflation.

Minsky rejected the idea that economics was primarily about “the allocation of given resources among alternative employments.” Like Keynes, Minsky took the central economic problem to be “the capital development of the economy,” which involved relying on a sophisticated financial system to facilitate the production of expensive capital assets.

The capital development of a capitalist economy is accompanied by exchanges of present money for future money. The present money pays for resources that go into the production of investment output, whereas the future money is the "profits" which will accrue to the capital asset owning firms (as the capital assets are used in production). As a result of the process by which investment is financed, the control over items in the capital stock by producing units is financed by liabilities--these are commitments to pay money at dates specified or as conditions arise. For each economic unit, the liabilities on its balance sheet determine a time series of prior payment commitments, even as the assets generate a time series of conjectured cash receipts.

What he’s saying is that business have to come up with money today (M) in order to fund their operations, without knowing whether the future will turn out the way they had hoped. When debt is used to finance a firm’s operations, it puts the business on the hook for a certain (i.e. known) sequence of future payments (debt service), with no guarantee that its future cash flows (M’) from running the business will be sufficient to service that debt.

Things might turn out well, in which case financial instability can be avoided. For example, when aggregate demand is durable, earnings from operations are strong, and free cash flows are sufficient to meet payment commitments, the system is generally stable. But there is always the chance that something will break. It’s basically about the relationship between income and debt and how it evolves over time. Here’s Minsky:

The first theorem of the financial instability hypothesis is that the economy has financing regimes under which it is stable, and financing regimes in which it is unstable. The second theorem of the financial instability hypothesis is that over periods of prolonged prosperity, the economy transits from financial relations that make for a stable system to financial relations that make for an unstable system.

Minsky described three distinct income-debt relations for economic units:

Hedge financing units are those which can fulfill all of their contractual payment obligations by their cash flows: the greater the weight of equity financing in the liability structure, the greater the likelihood that the unit is a hedge financing unit.

Speculative finance units are units that can meet their payment commitments on "income account" on their liabilities, even as they cannot repay the principle out of income cash flows. Such units need to "roll over" their liabilities: (e.g. issue new debt to meet commitments on maturing debt).

Ponzi units [where] the cash flows from operations are not sufficient to fulfill either the repayment of principle or the interest due on outstanding debts by their cash flows from operations. Such units can sell assets or borrow. Borrowing to pay interest or selling assets to pay interest (and even dividends) on common stock lowers the equity of a unit, even as it increases liabilities and the prior commitment of future incomes.

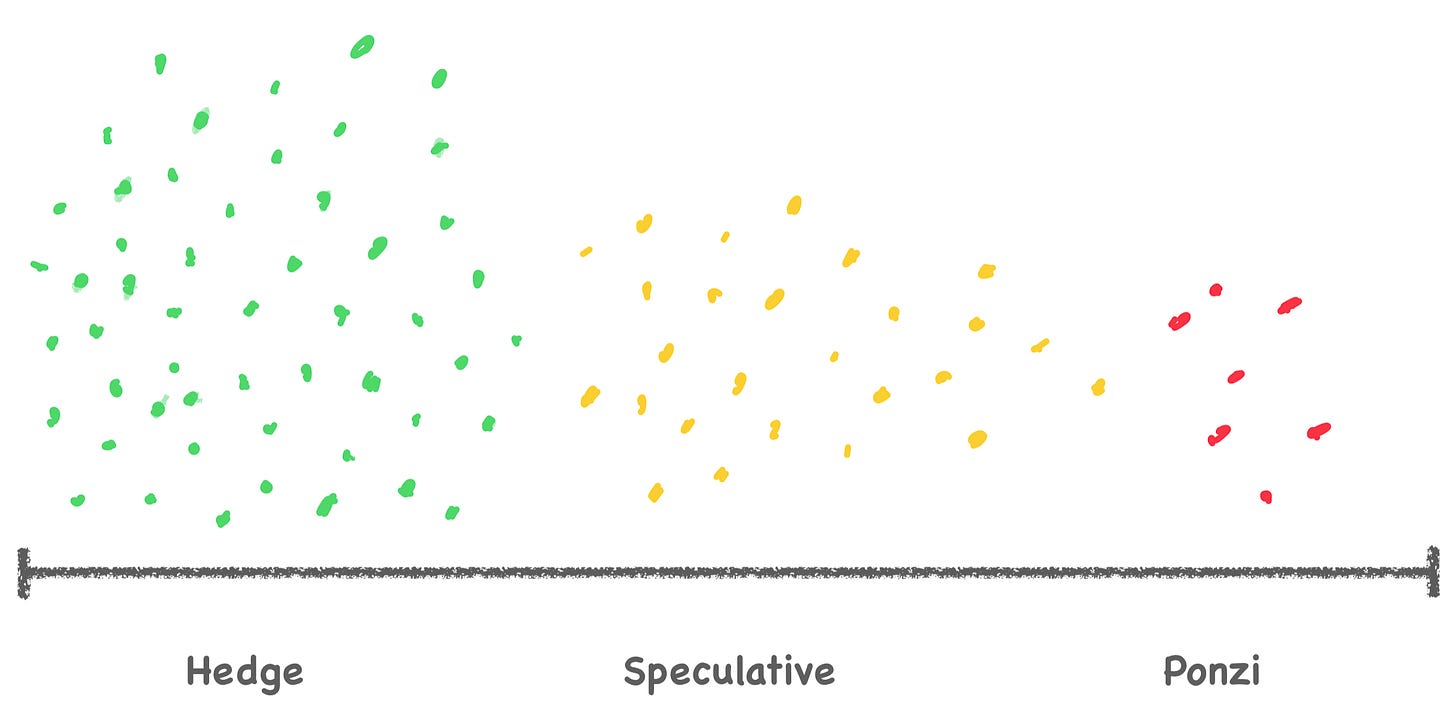

Minsky explained that we can think of a stable financing regime as one in which hedge financing dominates. I’ve always thought about it like this.

At any point in time, the economy is filled with hedge, speculative, and Ponzi units. There are always some number of Ponzi units kicking around, and there's nothing inherently wrong with a business that needs to roll over maturing obligations--i.e. a speculative unit. But the financial system as a whole is more robust when the mix looks something like what I’ve drawn above.

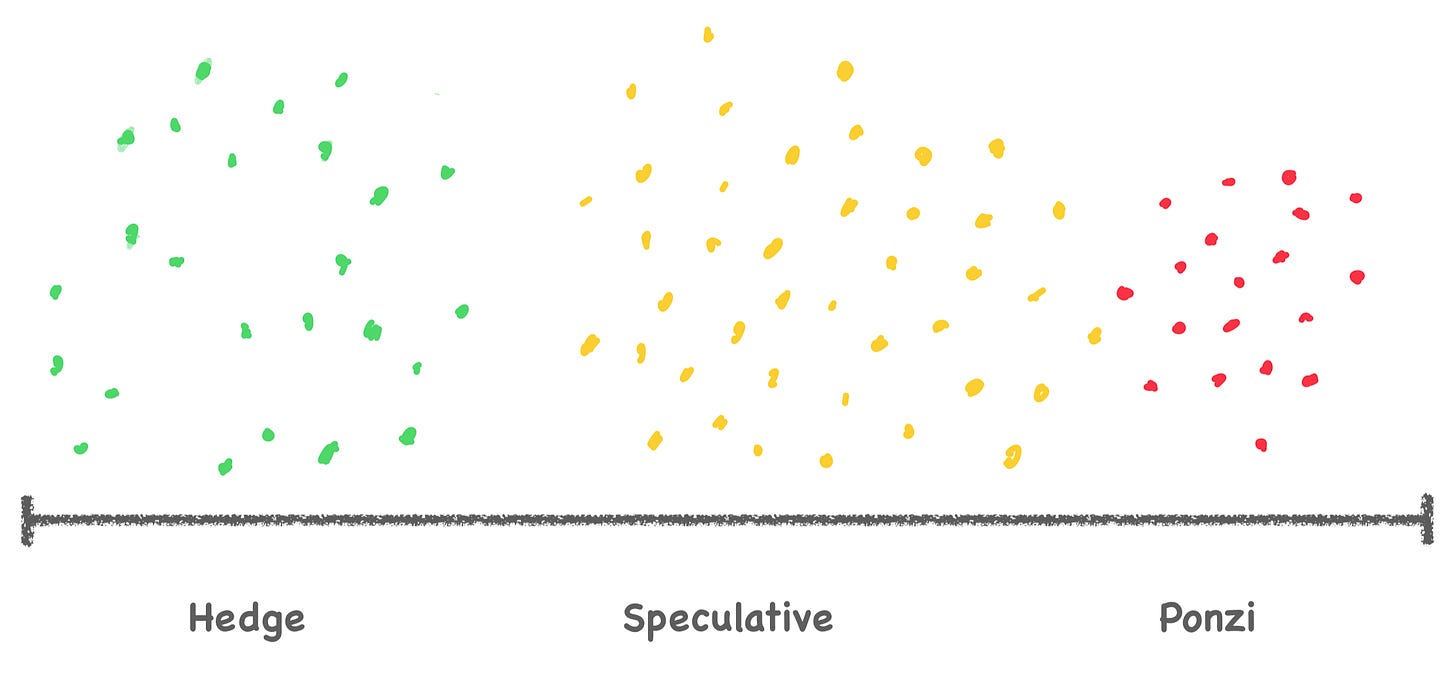

“In contrast,” Minsky explains, “the greater the weight of speculative and Ponzi finance, the greater the likelihood that the economy is a deviation amplifying system.” In other words, the financial system becomes more vulnerable when the mix changes to look more like what I’ve drawn below. With fewer hedge units and more speculative and Ponzi units, the stage is set for a potential crisis.

The picture can evolve slowly, or it can change quickly, and it can transition in either direction.1 When Minsky said that “stability is destabilizing,” he meant that borrowers and lenders tend to grow less cautious when times are good, allowing margins of safety to decline and debt-financing commitments to rise.

In particular, over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move from a financial structure dominated by hedge finance units to a structure in which there is large weight to units engaged in speculative and Ponzi finance.

If you think the US economy looks more like the first image than the second, then maybe you’re not as worried about the impact of the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes. That is, if households are sitting on little debt and plenty of cash and businesses have strong earnings and relatively low debt burdens, then maybe the rate hikes don’t trigger much distress.

But what if the rate hikes are pushing many units from hedge into speculative and from speculative into Ponzi positions? In that case, then we may be entering (or already in) a deviation-amplifying financial regime—i.e. one that is highly vulnerable to a breakage that spills over into the financial markets. As Minsky warned:

Furthermore, if an economy with a sizeable body of speculative financial units is in an inflationary state, and the authorities attempt to exorcise inflation by monetary constraint, then speculative units will become Ponzi units and the net worth of previously Ponzi units will quickly evaporate. Consequently, units with cash flow shortfalls will be forced to try to make position by selling out position. This is likely to lead to a collapse of asset values.

A sure path to a financial meltdown is via a combination of further aggressive tightening by the Fed and disappointing corporate earnings.

Speculative units can become hedge units if, for example, cash flows come in unexpectedly strong or interest rates fall, allowing repayment of both principal and interest.

It seems that the concept of the "Minsky Moment" is spreading through the mainstream as I have seen more references to it over the past few years. Unfortunately, I don't think it has reached the Fed and Jerry Powell.

Or, is it that their desire to suppress wages and grow the "reserve army of the unemployed" is more important than financial stability? From my POV it looks like the Fed is violating both sides of their dual mandate to promote financial stability and full employment.

It is, however, clarifying to see Powell admit that wage suppression is the goal. The wealthy elites running this economy really do hate the working class and they seem to find great pleasure in beating them down. Sad and disgusting.

Great article!