Yes, global supply chains are a mess. Yes, consumers are frustrated, paying through the nose for new and used vehicles, petrol, housing, and even blue paint. Yes, people are worried about getting ahold of the latest iPhone, a pair of Nike or Adidas tennis shoes, a Microsoft XBox Series X, or any number of popular toys in time for the holidays. And, yes, employers are complaining too, desperate to hire preschool teachers, construction workers, truck drivers, hotel and restaurant workers, and even dog walkers.

But there’s a bright side to the frustration and the pain associated with higher inflation.

It Beats the Alternative

Almost exactly 10 years ago, headlines were screaming, “Double-dip Recession!” CNN, The Economist, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and just about every other major news outlet cautioned that the fragile economic recovery from from the Great Recession was faltering. Larry Summers joined a chorus of voices, warning of a “1-in-3 chance” that the U.S. was entering a double-dip recession. (Yes, it’s a familiar prediction). Others put the odds closer to 50-50. The smell of contraction was in the air.

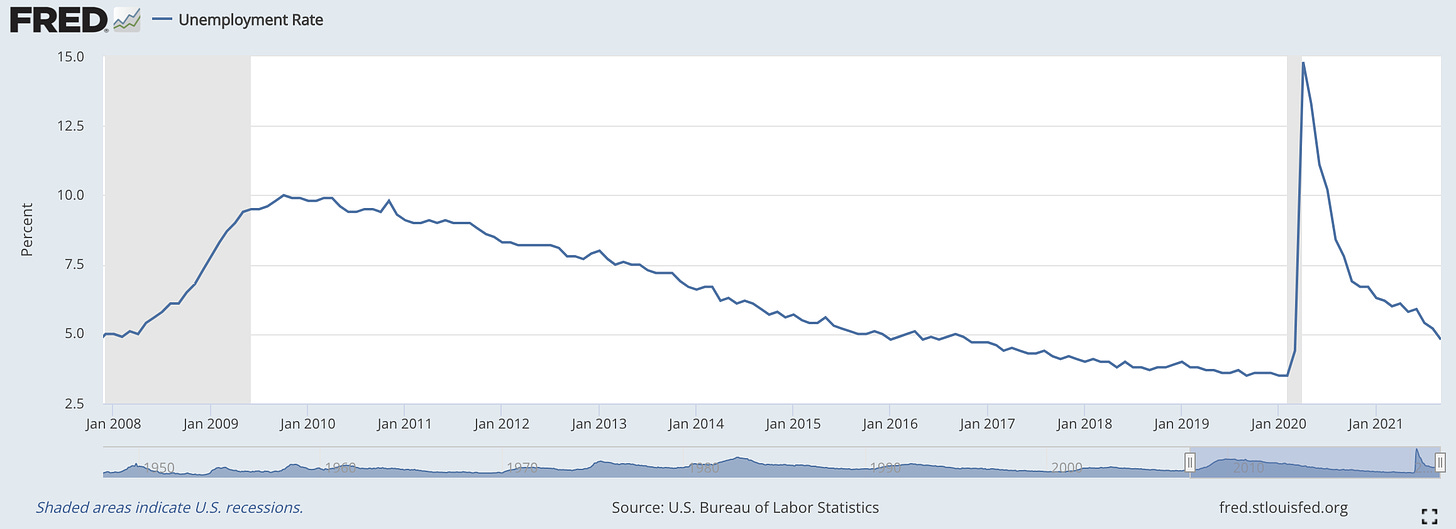

While the US was technically in its second year of an economic recovery, the unemployment rate appeared stuck at around 9 percent going into the fall of 2011. Job growth had slowed to the point that it was barely keeping pace with population growth. The boost that came from the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (which had been far too small to begin with) was fading fast, and there was little appetite for another round of fiscal support among lawmakers, as concerns over rising debt levels and the fiscal deficit took hold. It was basically one-and-done on the fiscal side, and then everything fell to poor Ben Bernanke, who tried to explain to Congress why the Fed wasn’t capable of restoring the labor market to full health. Testifying before Congress on June 7, 2012, Bernanke put it bluntly:

“Monetary policy is not a panacea. It is not the ideal tool.”

What was needed, he explained, was more robust support in the form of fiscal policy:

"I would feel much more comfortable if Congress would take some of this burden from us and address these issues.”

He didn’t get the help he was seeking. In fact, what got was exactly the opposite.

A fight over the debt ceiling resulted in passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which set the stage for the “fiscal cliff” drama in 2012 and the subsequent austerity imposed via budget “sequestration” beginning in 2013. In other words, fiscal policy swung from modestly supportive in 2009-2012 to an outright drag on economic growth.

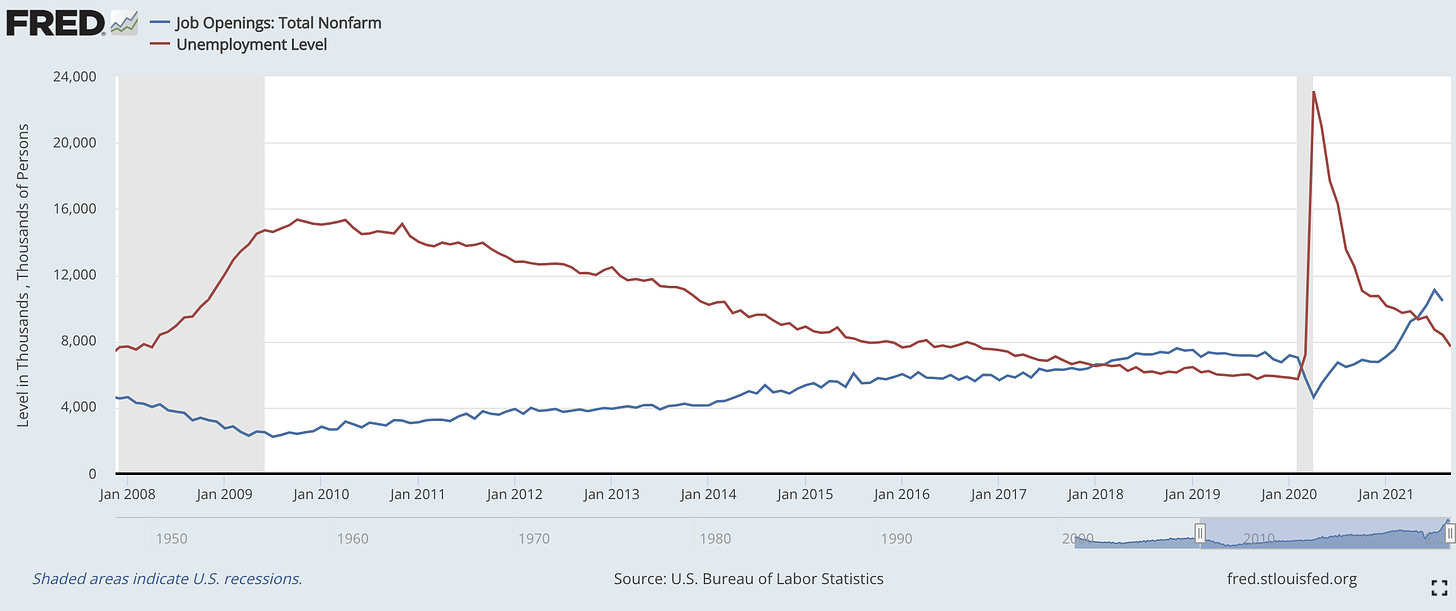

In spite of the fiscal drag, the much feared double-dip recession never materialized. Instead, the economy muddled along for another seven years. The gap between the number of people looking for work and the number of job openings slowly narrowed.

And the unemployment rate trudged steadily lower.

But it wasn’t exactly a pretty recovery.

It took more than six years to claw back the jobs that were lost in the recession. This chart from Calculated Risk became known on #FinanceTwitter as “the scariest” or “ugliest” jobs chart in history.

And while the economy eventually recovered all of the jobs that were lost in the Great Recession, the jobs that came back were disproportionately inferior to those that were lost. As Harvard economist Lawrence Katz and Princeton economist Alan Krueger famously documented, good jobs—stable, full-time jobs with decent pay and good benefits—became increasingly hard to find. Indeed, they found that a whopping 94 percent of the net job growth from 2005-2015 was in “alternative work.”1

With lackluster economic growth and workers forced to settle for low-paid, low-hours jobs, inflation remained trapped below the Fed’s 2 percent target for the better part of a decade.

So we got a long, anemic recovery with little inflation to speak of.

This Time is Different

When the pandemic began, Dr. Fauci predicted that an effective vaccine might be available within 12 to 18 months. Plenty of other infectious disease experts thought that was wildly optimistic, cautioning, “vaccine development is usually measured in years, not months.” Miraculously, things turned out even better than Fauci predicted, with the first COVID-19 vaccine in America administered to a critical care nurse on December 14, 2020.

The fiscal response also turned out better than almost anyone—myself included—would have expected. The $2.2 trillion CARES Act came together almost immediately, sailing through Congress in the first month of the pandemic. By December 2020, Democrats and Republicans joined to provide an additional $900 billion in fiscal support. Then, a few months after the first vaccine was administered, Congress—or should I say Democrats—delivered the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, which (among other things), put more money into vaccine distribution, sent $1,400 checks to most Americans, provided a $300 per week unemployment insurance supplement, and expanded the child tax credit. By summer, the National Bureau of Economic Research announced that the economy had not only recovered but that the COVID-induced recession was the shortest in U.S. history.

The ugly jobs chart was looking pretty good.

As my fellow Substacking economist and friend Claudia Sahm recently put it, Congress went “really big” and even with CPI running above 5 percent it was totally “worth it.”

Unlike the ugly wage and employment picture that characterized the Obama years, job vacancies are plentiful and employers are offering better pay and benefits in order to attract workers. And while it’s true that prices are rising faster than many workers’ wages, it definitely beats the alternative macro scenario.

A Good Problem to Solve

We have to compare where we are today with where we could have been if: (1) It had taken years and not months to develop an effective vaccine; and (2) Congress had pulled another one-and-done with fiscal support. So yes, we have problems to solve, but they are good problems to have.

We have cargo ships stranded at sea, freight companies looking for places to put containers and people to unload and transport goods, frustrated car buyers, a housing market that’s making it hard on first-time home buyers, and so on. And the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, core PCE, continues to run hot at 3.6 percent. But at least people have money to spend and jobs that require reliable transportation. And thank goodness they’re searching for childcare because it means that schools have mostly reopened, thanks to the vaccine.

The good news is that many of our supply-chain problems will resolve on their own. But there are also things we can do, proactively—like building out our domestic semiconductor capacity, investing in our ports and railways, strengthening our care economy, and vaccinating the world’s population.

The bad news is that our global supply-chain problems could get worse before they get better, climate change will pose ongoing disruptions to supply chains, new strains of the delta virus have already emerged, there isn't much the Fed can do, and we’re facing some fiscal headwinds. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP now forecast projects a remarkable slowdown (contra the consensus view) in the economy.

I don’t want to minimize the hardship facing tens of millions of Americans who are still struggling to pay the rent, put food on the table, find safe and decent work, and cover the cost of child care.

President Biden’s Build Back Better (BBB) plan wouldn’t solve all of our problems, but it would bring significant relief. The full $3.5 trillion BBB package, coupled with the $500 billion basic infrastructure, would have attenuated some short-term labor market pressures (e.g. by investing in child and elder care). It would have helped on the climate front. And, as 17 recipients of the Nobel Prize in economics recently wrote, it would help to mitigate inflation in the years ahead:

“Because [the Biden] agenda invests in long-term economic capacity and will enhance the ability of more Americans to participate productively in the economy, it will ease longer-term inflationary pressures.”

Unfortunately, Democrats are busy negotiating (with themselves) down the size and scope of the president’s agenda. At this point, who knows what—if anything—will pass. What I do know is that nothing will kill off the temporary bout of higher inflation like a self-inflicted slowdown.

Think independent contractors, temp agencies, freelancers, on-call employees, etc.

Hi Stephanie, great piece! Do you think at some point you could write about the various measurements of inflation (CPI, PCE, "core CPI"), which ones matter most, and why they variously include or exclude food, energy, and housing? Thx!

A bit of inflation has been well worth avoiding all the other far worse outcomes from the pandemic. I’ve also learned more about how Modern Monetary Theory describes our post-Bretton Woods monetary system.