Last month, I was in Brussels for a client event. Instead of the usual keynote address, I did a fireside chat with one of their senior market analysts. He put seven questions to me and then moderated an extended Q&A with the audience. It was a lot of fun.

Unfortunately, because it was a private event, there’s no recording for me to share with you. But I thought the questions—and my responses—might be of interest. To avoid writing one really long post, I’ve decided to divide it into a seven-part series.

I’ll answer the first question today, but here’s a preview of what’s to come.

Question 1: You say that the deficit can be too big and that inflation could be evidence of a deficit that’s too big. Is the deficit too big? If that is the case, shouldn’t Congress pass immediate tax hikes or spending cuts? Would it be politically possible?

Question 2: If Congress is not able to tighten fiscal policy because of low acceptability or political stalemate, does this mean that independent central banks are better placed to fight inflation?

Question 3: MMT seeks a low rate of unemployment. Does it run the risk of getting an insufficient return on investment?

Question 4: Governments can create money out of thin air to finance their investments. Did the pandemic force this truth out and create a dangerous precedent. Won’t people now expect more borrowing to pay their pay rises and/or consumption?

Question 5: How much government debt is too much ? Is only the US exempt from debt ceilings ?

Question 6: Is more inflation welcome to solve for excess debt levels?

Question 7: Should the government set interest rates in your view – where would you take rates in 2022?

Question 1: You say that the deficit can be too big and that inflation could be evidence of a deficit that’s too big. Is the deficit too big? If that is the case, shouldn’t Congress pass immediate tax hikes or spending cuts? Would it be politically possible?

Let’s start with the first part of the question. It is certainly true that government deficits can be too big. No MMT economist has ever disputed that.1 What we have argued from the very beginning is that contra conventional arguments about budget deficits and fiscal sustainability, the relevant constraint on government spending is inflation.2

Here’s MMT economist L. Randall Wray in 2009:

It would clearly be inflationary to keep pushing the deficit beyond the level required to achieve full employment. But up to the point of full employment, deficits are not necessarily inflationary. Still, policy needs to be aware of bottlenecks and other structural problems that can generate inflation even before full employment.

There are three points here:

When there is untapped capacity in the economy—i.e. unemployed labor, idle or underutilized factories and equipment, and readily available raw materials—government deficits are not inherently inflationary (e.g. 2000-2020)

Inflation can begin to accelerate even before the economy runs out of spare capacity (e.g. 2021)

Government deficits that attempt to push an economy beyond full employment will push prices higher (e.g. WWII)

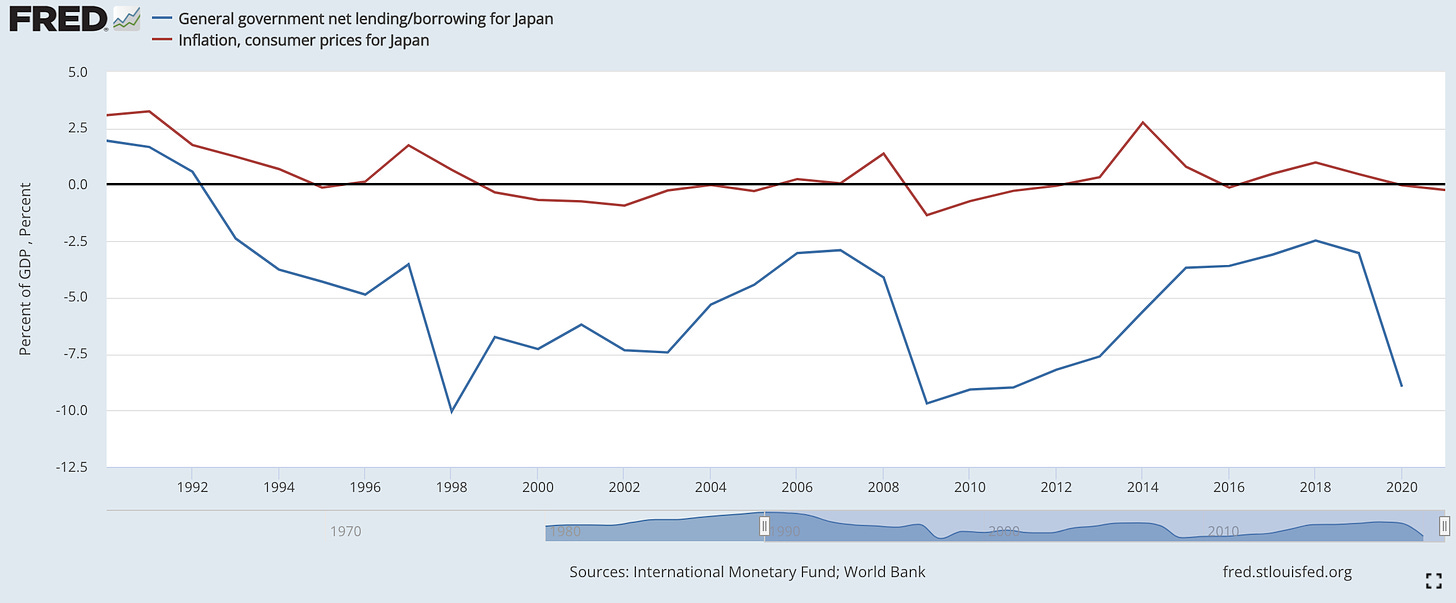

These aren’t controversial points, even among mainstream economists. Yet they often get lost in the popular discourse. For example, it’s not uncommon to hear lawmakers, media pundits, and other commentators refer to deficits as “evidence of overspending,” as if they naturally embody higher inflation.3 So it’s important to remember that government deficits (even big ones) can coexist alongside low inflation (or even outright deflation) for prolonged periods of time. That was the situation in Japan for the last three decades.4

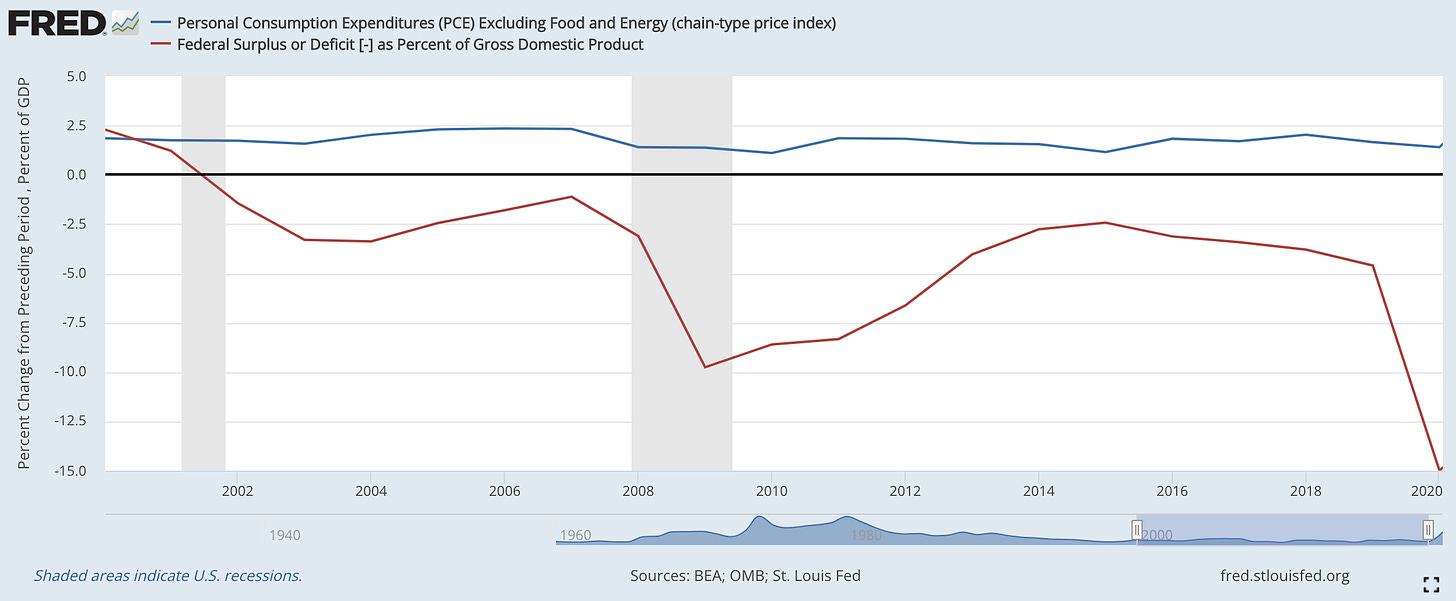

And until COVID came along, it was also the US experience (sans the deflation). Like Japan, the US experienced decades of persistent (and often rising) fiscal deficits with little pressure on inflation. Even as the deficit surged above 10 percent in the wake of the Great Recession, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure—core PCE—averaged just 1.6 percent from 2009-2019.

So MMT urges us to think about the economy’s productive capacity when we’re talking about the limits on spending. And it reminds us that government spending is only one component of total expenditure. Any claim on an economy’s productive capacity that comes from government spending has to mix in with household consumption, business investment, and net exports. It’s aggregate demand, relative to productive capacity, that matters when it comes to so-called “overheating.” When demand leakages rob the economy of too much demand, even large fiscal deficits may not move the needle on inflation.

Getting back to the question, the answer is yes. Fiscal deficits can be too big, and inflation can be evidence of a deficit that has gotten too big. But that is not—and this is really important—tantamount to saying that any increase in inflation is de facto evidence of a deficit that is too big. Government deficits are only one potential source of inflationary pressure. It’s always possible for CPI (or PPI or PCE) to rise for reasons unrelated to swings in the fiscal deficit.5 My view is that the much-maligned American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act (March 2021), which reduced unemployment and boosted real GDP growth, had only a modest impact on overall inflation. That’s also what the chief economist and his team at Moody’s Analytics have found.

Even if you believe the ARP was much too big, the reality is that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has just announced that the federal budget deficit is expected to shrink to $1 trillion in 2022, down from $2.8 trillion last year. That is the most rapid collapse in the fiscal deficit in my lifetime.

Here’s what I wrote back in March:

[T]he rapidly shrinking government deficit is acting as a drag on the economy. It’s not nearly enough to snuff out the recovery, because private sector demand has been strong enough to more than offset the fiscal drag. Still, the combined impact of state, local, and federal fiscal policy did shave an estimated 3.3 percentage points off of GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2021. Biden should be mindful about actively trying to shrink the deficit even faster.

Since then, we’ve seen some softening in the labor market, a big drop in new home sales, and some increasingly worrying retail data.

So do I think Congress should be working with the White House to pass immediate tax hikes or spending cuts in order to bring down inflation? No. There’s already more than enough fiscal tightening baked in.6 What’s needed now is a continued focus on repairing supply-chains, a concerted effort to get vaccines to countries with low vaccination rates, a resolution to the war in Ukraine, strategies to reduce gas prices, and a plan to secure the global food supply in the face of looming shortages.

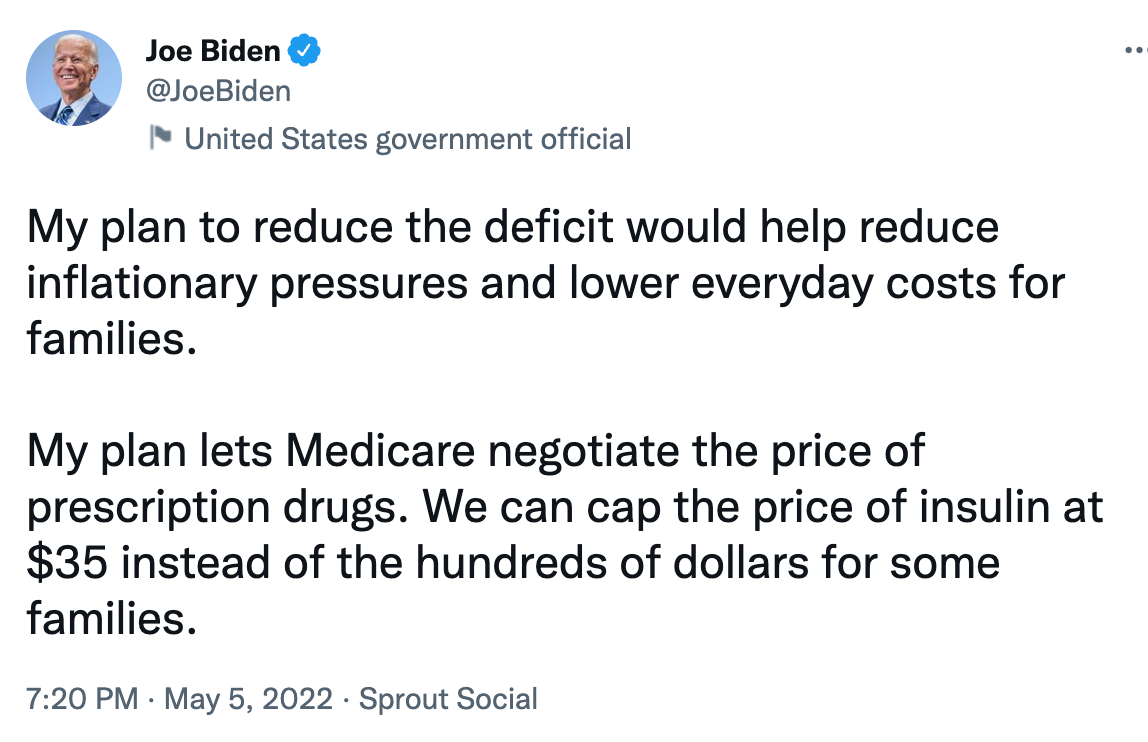

Although I wouldn’t prioritize deficit reduction, the White House is hoping to reach a deal with Congress that would raise taxes by more than enough to offset some proposed new spending. While I don’t agree that we need to cut the deficit even further in order to bring inflation down, the president is pushing it.

Even if democrats don’t ultimately vote for Biden’s plan, it’s clearly possible for lawmakers to dial back fiscal support when confronted with high inflation. Remember, Congress already massively tightened fiscal policy.

A final Word

Earlier today, we learned that inflation moderated somewhat in April. It’s still unacceptably high, and it’s important not to read too much into one monthly report. But this was welcome news.

There are obviously some pretty big wild cards—Ukraine/Russia/China—but as Claudia Sahm wrote in her Substack this morning, “we are on track for core inflation in the second quarter to step down to around 4% at an annual rate from the 5% pace in the first quarter.”

Claudia spent many years working at the Fed, and she’s right to note that the FOMC will carry on raising rates until it sees “clear and convincing evidence” that inflation appears to be heading back down to 2 percent.

I wish that wasn’t the case. I’ll explain why when I answer Question #2.

If you hear someone say, “MMT argues that there are no limits on government spending,” do yourself a favor and walk away. For there is no surer sign that you have encountered a bad-faith actor or a sloppy thinker.

The caveat here is that we are talking about governments that operate with a sovereign currency, as explained here.

Senator Mike Enzi (R-WY) was the Chairman of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee when I served as chief economist to the Democrats back in 2015/16. Like many Americans, Sen. Enzi interpreted the mismatch between outlays and receipts—i.e. the fiscal deficit—as “evidence of overspending.” The government should, he routinely lectured, learn to “live within its means.”

If you’re interested, we’ve written about how to think about the Japanese experience from an MMT perspective.

It’s also possible for inflation to increase (or remain elevated) even in the presence of a rapidly falling deficit or a growing budget surplus.

As I pointed out in a recent appearance on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast, the deficit is already collapsing rapidly. You don’t have to raise tax rates to raise tax revenue. Fiscal tightening is baked in, partly because of our progressive tax code (higher nominal income growth) but also because a lot of fiscal support (expanded child tax credit, direct cash payments, etc.) that was was in place in 2021 is gone now.

"It's also possible for inflation to INCREASE [an editing glitch?] (or remain elevated) even in

the presence of a rapidly falling deficit or a growing budget surplus."

Exactly. Let's try this thought experiment. Pre-pandemic, the so-called "national debt" (accumulated annual federal deficits) was about $28 trillion while inflation was running at or below 2%. How could these 2 seemingly competing facts be true at the same time? Part of the explanation is surely that an enormous chunk of that $28 trillion was captured (a la Thomas Piketty) by the top 1%--who, because they have more money than they can reasonably spend, have a high propensity to save. A dollar NOT chasing goods and services doesn't fuel inflation.

But suppose the gov't decides that, even though it really doesn't need their money, it is going to tax the uber wealthy to reduce their political clout while at the same time helping out the little guy. So the gov't claws back $1 trillion in taxes from the rich (don't think of it as "revenue" because the money gets applied to debits in the Treasury's account at the Fed and the money simply disappears) and then issues ARP checks (new money created out of thin air) to low-income Americans totaling $500 billion. The deficit has just been reduced by $500 billion, but what is your prediction about the inflationary effect of those ARP checks? Well, if the economy is already running at full capacity, then this injection of $500 billion (low-income recipients will spend every penny of it) has to juice up inflation. So here it seems we have a case of LOWERING the deficit is INFLATIONARY.

And doesn't this example highlight a fundamental injustice in the way our economy works? The poor can't win for losing.

There have to be other measures than have been discussed to curb the Hedge Funds interfering in the Housing market, rich corporations raising costs with Stock Buybacks, lack of competition in the food markets, and the growing gap between the rich and the poor which leaves our economy totally schewampus.