Flipping the Script

In tonight's presidential debate, both candidates should explain who will benefit from their proposed deficits.

Later today (9:00pm ET), Vice President Harris and former President Donald Trump will square off in their first (and perhaps only) debate before the November election. The moderators—two ABC News anchors—will press the candidates to answer questions about a wide range of important domestic and foreign policy issues. They will also, almost certainly, ask them to articulate their plans for dealing with government deficits and the (so-called) national debt.

As president, Donald Trump never gave the deficit much oxygen. He only used the word “deficit” twice during any State of the Union (SOTU) address, once in reference to America’s trade deficit and then again when he described the nation’s infrastructure deficit.

To those who squawk incessantly about debt and deficits, Trump’s indifference to the budgetary effects of his policies was seen as reckless and unserious. He simply didn’t care. In fact, back in 2019 when ABC News asked Trump’s Acting Chief of Staff, Mick Mulvaney, whether the president was going to comment on the government’s ballooning deficits, Mulvaney simply replied, “nobody cares.”

Trump was right. Almost no one in America is lying awake at night worrying about the government’s finances.

Every Deficit is Good for Someone

What Trump appears to have understood—and, frankly, what republicans have long known—is that every deficit is good for someone. Why is that? Because, as the sector financial balance (accounting) framework reminds us, on the other side of every government deficit lies a financial surplus that accumulates in some other part of the economy.1 Why do republicans tend to run up the deficit whenever they get the chance? Because they know that it produces a windfall for someone else.

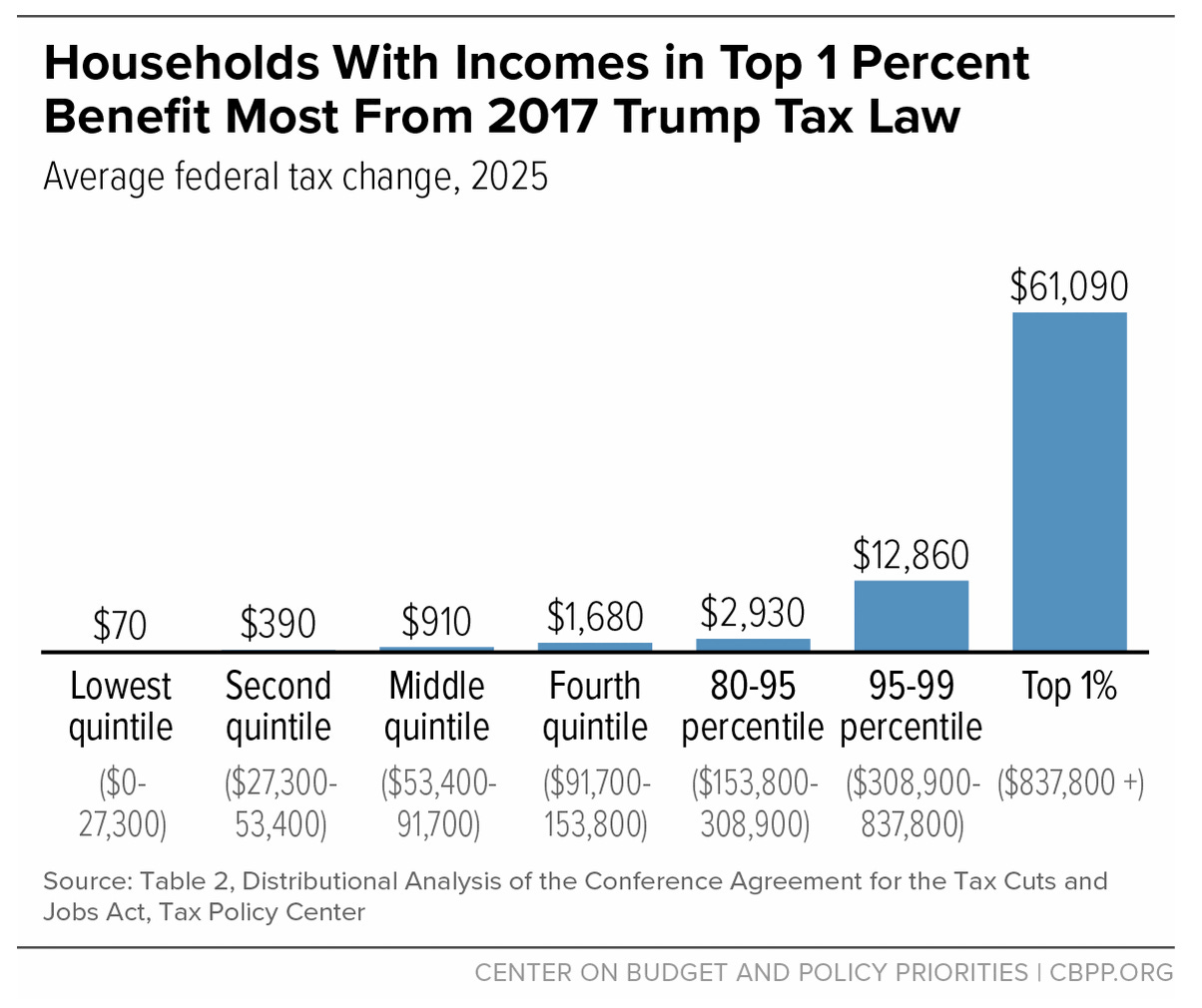

Remember the sweeping tax cuts that were passed in 2017 when republicans had control of the House and Senate? They added an estimated $1.9 trillion to government deficits. Republicans voted for that legislation knowing that those deficits would feed almost two-trillion dollars into the non-government sector. But where did that windfall go? The answer is that the vast majority went to large profitable corporations and the wealthiest people in America. Remember, every deficit is good for someone. As you can see below, the deficits created by the Trump tax cuts were really really really good for the folks in the top 1%.

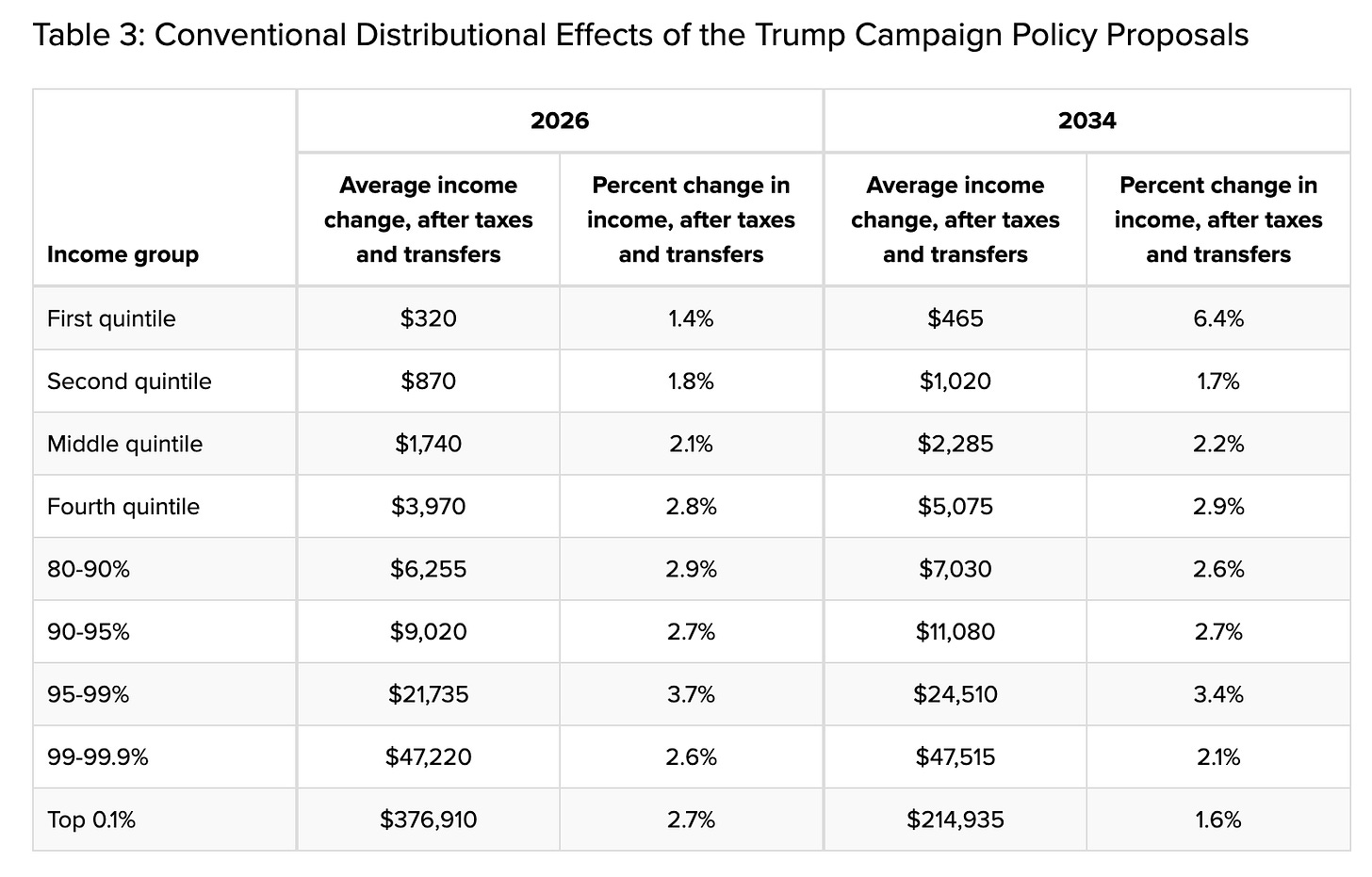

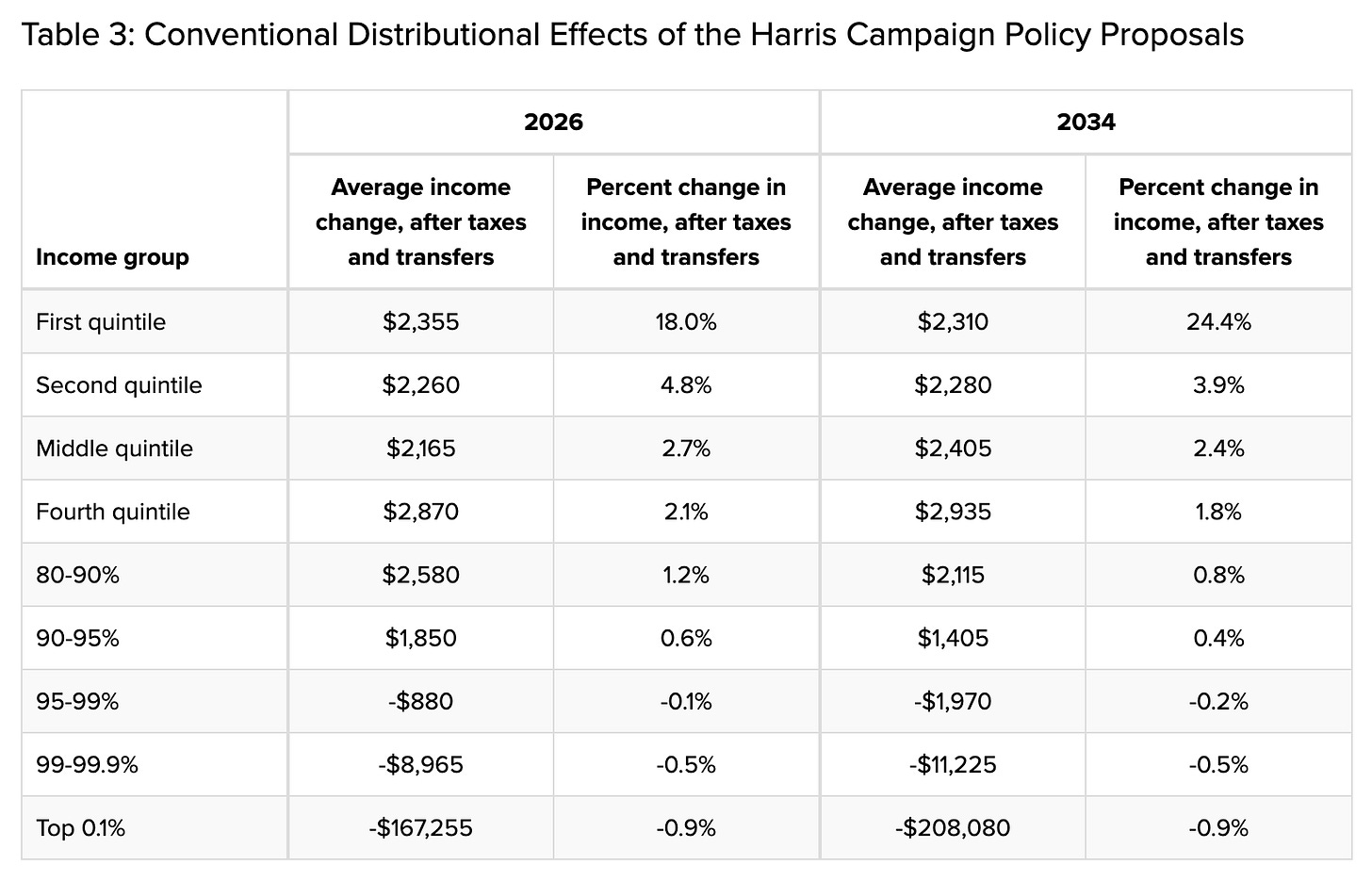

If given the chance, Trump will return to the White House with an agenda that would increase (primary) deficits by an estimated $5.8 trillion over ten years. The same budget model finds that Vice President Harris’s policies would increase deficits by $1.2 trillion to over the same period.

Is bigger better?

While it is an indisputable fact to acknowledge that every government deficit is matched, dollar-for-dollar, by a financial surplus in the non-government sector, it would be foolish to conclude that the best set of policies is the one that dumps the biggest pile of cash into the broader economy. Yes, every deficit is good for someone. But for whom? Can it be done without stoking inflation? And what are those deficits helping us to accomplish as a society? Fatter wallets for those at the very top or safer communities, better health outcomes, and a cleaner environment?

When the question is put to both candidates tonight, instead of pointing fingers and waging a rhetorical war against government deficits, both candidates should take a deep breath and explain how they plan to use the deficit to deliver material gains for the American people. The moderators should know this too. They should press each of the candidates to explain who will benefit (and how) from the contributions that their deficits will make to the broader economy.

For example, Donald Trump should be asked why, according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, the benefits of his large deficits would go—yet again— disproportionately to folks at the top of the income distribution. Instead of making him defend the budgetary effects of his agenda, make him defend the distributional effects!

When the moderators (inevitably) fail to do this, the Vice President should do it for them. She can point to the same budget model, which shows that her deficits are designed to benefit a very different constituency—i.e. the vast majority of working class Americans.

Voters care about what each of the candidates would do as president. Policy matters. But it’s at least as important—and probably more so—to show them who you’re fighting for.

Over time, the flow accumulated deficits pile up into a stock of safe assets issued by the U.S. Treasury—government securities known as T-bills, notes, and bonds. The stockpile of Treasuries is, colloquially referred to as “the national debt,” an unfortunate way to refer to the funds held in these government savings accounts.

Elegant. Perfect. (Well, I suppose you might have said “his alma mater Penn Wharton’s…”) And if this explanation and argument doesn’t make it to the debate stage tonight, it could and should become the foundation of every Harris speech for the next 56 days.

Deficit spending ultimately regresses to political cronyism. ALL deficits end up with the “one percent” via retained earnings (accounting). As such, it is indisputably valid to conclude that deficit spending is, by definition, THE cause of inequality.

Deficits facilitate accelerated speculation and result in unnecessary strain on the financial sector, which Minsky summarizes as stability breeding instability. Last, deficit advocates overlook Keynes’ concept of effective demand (the limit to growth), thereby exacerbating financial bubbles.