Yesterday, I listened to an interesting podcast conversation between the New York Times’ Ezra Klein and Columbia University’s Adam Tooze. Tooze is an economic historian, whose new book challenges conventional economic thinking in ways that often closely parallel Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

For the last quarter-century, MMT economists have emphasized that “finding the money” is never the challenge for governments that issue their own non-convertible—i.e. floating exchange rate—fiat currencies. It has long been our position that mainstream macro, which centers the limits of fiscal policy around the (erroneous) concept of a “government budget constraint,” has led us astray.

Instead of treating governments like revenue-constrained households, MMT economists have pushed for a macro framework that replaces the artificial government budget constraint with a real resource (inflation) constraint.

A central tenet of MMT is captured in the recognition that a currency-issuing government can afford to purchase whatever is available and for sale in its own currency. Before COVID, it was harder to persuade people that the government could easily afford to spend trillions without raising a slew of taxes to “pay for” it.

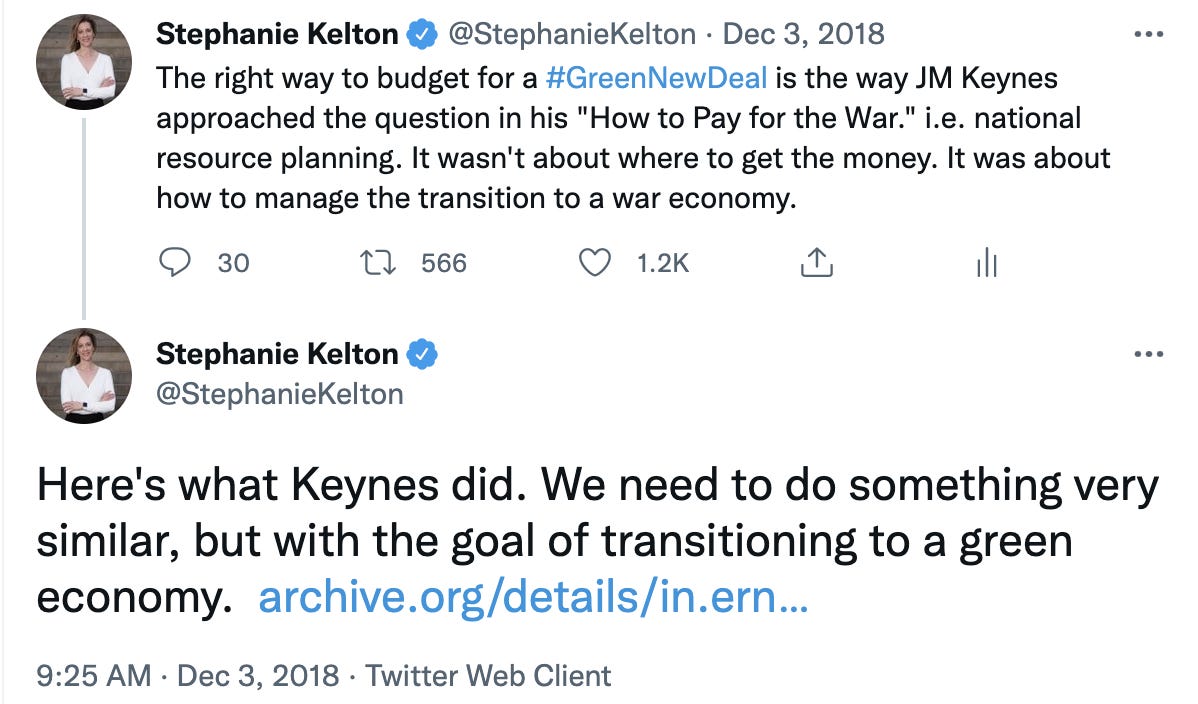

I still remember the pushback I got from some economists back in 2018 for including this line in a co-authored piece called We Can Pay For A Green New Deal. I wrote:

“Anything that is technically feasible is financially affordable.”

I was making the case that the federal government can afford to do big, transformative things, like tackling our climate crisis, without obsessing over the usual question of how to “pay for” it. Finding the money is the easy part—new money is created whenever the government spends. The challenge, I argued, lies in managing bottlenecks and other inflationary impulses along the way.

I suggested that if policymakers were serious about a mass mobilization of resources to transition our economy away from fossil fuels, they would be wise to draw inspiration from John Maynard Keynes.

There wasn’t exactly a groundswell of support for these arguments several years ago, but as Tooze notes, COVID-19 has made it much harder to dismiss them today.

Here’s Tooze in a recent essay for The New York Times.

“The world discovered that John Maynard Keynes was right when he declared during World War II that ‘anything we can actually do, we can afford.’ The sheer scale of the action was intoxicating. Among the left wing of the Democratic Party, it generated excitement: If money was a mere technicality, what else could be done? Action on social justice, climate change, the Green New Deal, all seemed within reach.

….

We can afford anything we can actually do. The problem is agreeing on what to do and how to do it. In giving us a glimpse of financial freedom, 2020 also robbed us of pretenses and excuses. If we are not doing a global vaccine plan, it is not for lack of funds. It is because indifference, or selfish calculation — vaccinate America first — or real technical obstacles prevent us from ‘actually’ doing it.

It turns out that budget constraints, in all their artificiality, had spared us from facing the all-too-limited willingness and capacity for collective action. Now if you hear someone arguing that we cannot afford to bring billions of people out of poverty or we cannot afford to transition the energy system away from fossil fuels, we know how to respond: Either you are invoking technological obstacles, in which case we need a suitably scaled, Warp Speed-style program to overcome them, or it is simply a matter of priorities. There are other things you would rather do.”

Tooze explains that whether we’re talking about rescuing Wall Street from its own excesses after the 2007/8 financial crisis or rescuing the American economy during the pandemic:

“[T]he digital money creation was the easy bit.”

If the federal government is prepared to act boldly, there is no hard budget constraint to stop it.

Saying the Quiet Part Out Loud

The podcast unfolds against the backdrop that the federal government isn’t revenue constrained and that the mainstream has either led everyone astray—especially when it comes to debt and deficits—or failed to articulate what many in the profession now claim to have understood all along.

Ezra Klein says this to Tooze:

“I want to bring up something…which is how the boundaries of acceptable thought are policed and defined within the economics profession. I want to go back to the line you began with that ‘Whatever we can do, we can afford.’ This is a line that I have talked about with some leading, center-left economists and they’ll tell you that, of course they know that. They’ve always believed that. Modern Monetary Theorists love quoting this line, but they’ll say the Modern Monetary Theorists have nothing new to say, that’s just an old Keynes line.

But I will say, that having covered economics for a long time in Washington that was not a line that used to get quoted to me…

I think there’s a lot of fear that if it becomes known. If it becomes believed…that whatever we can do we can afford that that will be used irresponsibly…and create a lot of real problems like runaway inflation…

The profession wants to say, ‘No, we knew all this,’ but in fact they haven’t been saying it because they’re a little bit afraid, in my view, of what people will do with these ideas if they get hold of them. If they’re sort of not protected by the responsible economists placing boundaries on what is and isn’t sober-minded policymaking.”

In other words, MMT reveals something that is simultaneously obvious within the economics profession but too dangerous to share with anyone on the outside.

To police the boundaries on policymaking, mainstream economists brandish concepts like intertemporal government budget constraints, debt-to-GDP tipping points, non-accelerating inflationary rates of unemployment (NAIRU), neutral rates (r*), unanchored inflation expectations, etc. To the uninitiated, concepts like these become the “scientific” evidence that necessitates policy restraint.

I don’t know whether Ezra has ever seen this clip of Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson, but it captures his sentiments perfectly.

It’s as if the center-left economists Ezra is referring to—people like Larry Summers—see themselves sort of like Lloyd Blankfein saw Wall Street’s biggest banks—i.e. merely doing God’s work.

Whether he’s policing the Biden agenda or closing ranks to marginalize MMT within the economics profession, Summers has a history of going the extra mile to define the boundaries of the possible. Fortunately, Congress and the White House turned a deaf ear to Summer’s vocal critique and moved forward with the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Act in March 2021.

For those who may not remember, Summers had previously tried (again unsuccessfully) to dissuade lawmakers from passing a major piece of legislation in 2017. Back then, he was certain that passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would mean:

“Our country will be living on a shoestring for decades because of the increases in the deficit that will result.”

It was a bad call.

The tax cuts passed, adding nearly $2 trillion to deficits. And then, a few years later when COVID ravaged our shores, Congress began spinning out multi-trillion dollar spending packages without the slightest affordability problem, proving that whatever we have the political will to do, we can afford.

As Ezra put it:

“I would say the economics profession has just been devastatingly wrong about what effect different deficit levels would have over the past twenty years. I think you simply have to look at that, given the credentials of some of the people making these arguments, as—in aggregate—a record of a lot of failure…There were just a lot of warnings that just look completely ridiculous.”

Next On Tap

This isn’t the post I sat down to write, but I wanted to lay this foundation before tackling the next set of questions. Here’s where we’ll go next…

If MMT (and Keynes and Tooze) are correct that anything we can actually do, we can afford, then how do we operate in a world where that truth is revealed to the broader public? Are MMT economists too cavalier about the risks of inviting everyone in on the secret? Is honesty really the best policy, or do we need deficit myths and old-time budgetary religion to protect us in a world of uncertainty? Can we trust the MMT framework to guard against excesses?

As always, thank you for spending a bit of your time here with me.

Stephanie Kelton asks, "[D]o we need deficit myths and old-time budgetary religion to protect us in a world of uncertainty?"

Who are "we" and "us" in that question? No doubt you're using them rhetorically, but I fear that could boomerang on you (and, in non-rhetorical sense, us). The Washington Democrats (ranging from Schumer to Pelosi to Manchin) still need those myths to one degree or another. The Washington Republicans need them when they're not in power. As Tonto said to the Lone Ranger, ....

"Are MMT economists too cavalier about the risks of inviting everyone in on the secret?" No. The Rs figured it out with the Bush and McConnell-Trump tax cut for the rich.