A lot of people I know think that the Federal Reserve (and most other central banks) has permanently abandoned zero interest rate policy (ZIRP). While the Fed is widely expected to cut rates (at least a handful of times) this year, many of the economists I’m talking to are convinced that we are never ever getting back together with zero. (Apologies to T. Swift)

I’m not so sure.

Texting back-and-forth with a fellow economist last night, I wrote:

If the next crisis can be dealt with by cutting a few hundred basis points, standing up new lending facilities, modifying regulations, etc., then we don’t get all the way down to zero. But if the wheels are coming off big time, then down we go. I readily admit they want to avoid ever returning zero, but they will if they have to.

He replied (with a Minsky reference at the end):

I agree. I would argue that if the Fed keeps rates high, the household sector won't be able to handle it much longer. Everyone acts like 2000-2019 was the aberration. I still think that is normal. We fixed household balance sheets during COVID but then went right back to business as usual. The 2000-2019 era rates will all come back IMO until we figure out that Wall St should follow the real economy instead of lead it. It’s like people think there's no more money manager capitalism anymore.

A couple of hours ago, a different friend (also an economist), pointed me to this Axios post, which looks at the Hard Questions Raised by the ZIRP Era. So it seems lots of people are thinking about ZIRP. This friend thinks we’ve escaped ZIRP for good, and he is darn happy about it. His gut tells him that “because Covid showed the power of fiscal policy,” we’re more likely—politics willing—to pull the fiscal lever when the next crisis comes. I wish I shared his faith.

I e-mailed back:

I agree that Powell & Co will do whatever they can to avoid returning to a zero interest rate world. Until we know more about the origin/nature of the next crisis, it is hard to opine with much conviction. True, we know the power of fiscal policy, but we also know (I think) that many lawmakers will have a hard time voting for a fiscal package when a great many of them erroneously believe: (a) that fiscal policy unleashed near-double-digit inflation; and (b) that debt and deficits are already out of control. Fortunately, the automatic stabilizers will push the budget in the right direction, but (again, depending on the nature of the crisis) it may not do enough to keep things from getting ugly.

I have low conviction about everything right now. I don’t understand this market. The rate hikes are pushing hundreds of billions of dollars in additional interest income out each year. This is driving the deficit higher and higher. CBO projects that deficits will average $2T (annually) over the next decade. But the very same CBO report also tells us that real GDP and PCE inflation will run about 2 percent over the same time period. So excuse me for asking, but where exactly is the problem?!! If the SEP looked like the CBO forecast, Powell would be on TIME Magazine’s short list for Man of the Year. Who on earth cares about the numbers that fall out of the budget box at the end of each year if they are consistent with full employment and price stability!?

Fiscal policy plus a decade of ZIRP foamed the runway, making it possible for the Fed to go from 0 to 525bps without (much) collateral damage. Companies termed out debt. Almost 40% of homeowners own their homes outright. The rest are mostly locked in around 3%. But problems in CRE are very real. The banking sector is probably poised for major consolidation. And equities (and crypto) smell irrationally exuberant. Germany, the UK, and Japan have all entered technical recessions. Real estate problems in China and elsewhere, and who knows where all of the risk is buried? So what breaks first, and does it metastasize beyond what central banks can manage? And if it does, how will the discretionary side of fiscal respond with a divided Congress already worried about debt and deficits? My gut tells me the Fed may be the only game in town. Not sure we get all the way to ZIRP, but I wouldn’t rule it out.

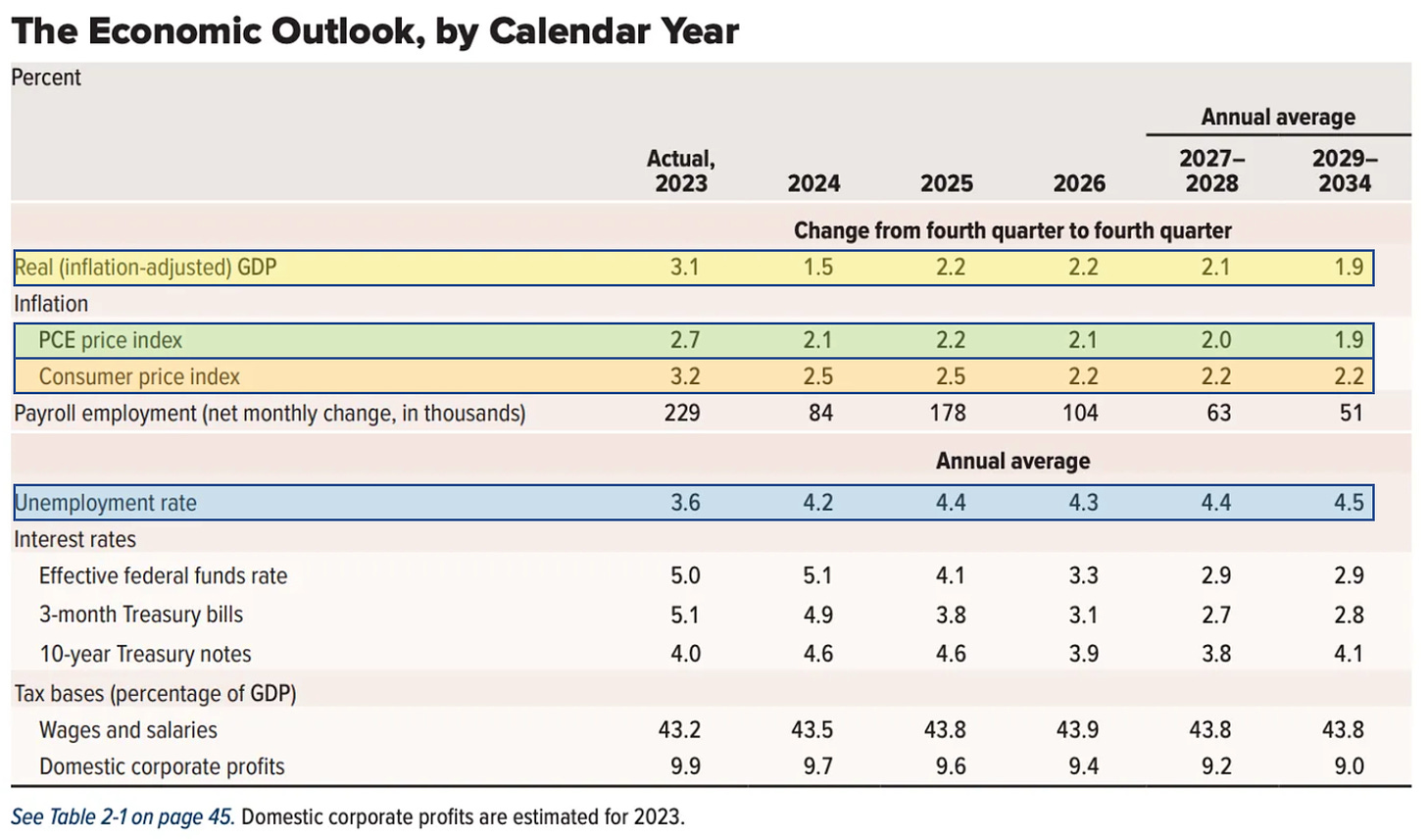

You probably heard a lot of talk about CBO’s latest budget projections. Nearly everyone seems to be raising alarms about deficits and a soaring debt-to-GDP ratios. But have a look at the economic outlook from the same report. Inflation runs right around 2 percent over the next decade, while the economy grows at about the same rate.

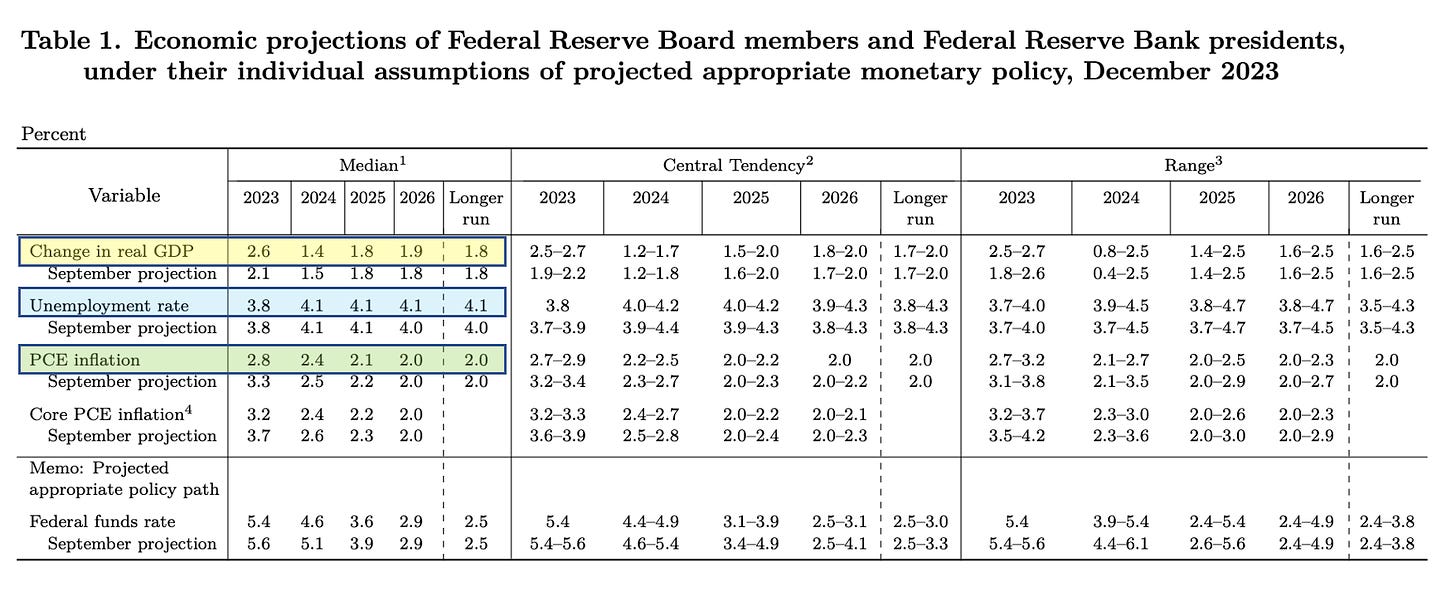

Now take a look at the median projection from the Federal Reserve’s latest Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).

There isn’t a huge difference between the two. Both show inflation returning to 2 percent. And while the Congressional Budget Office projects slightly faster growth and relatively higher unemployment, most economists and market analysts would probably describe either set of outcomes—if they were to materialize—as a “soft-landing.”

Which takes me back to something I used to say a lot: If you don’t have credible evidence of a long-term inflation problem, then you don’t have a long-term debt problem. A point I will come back to in a forthcoming post.

Until then, these are my musings on ZIRP. I’ll be on CNBC’s Squawk Box at 8:30 ET on Wednesday morning. Maybe some of this will come up.

Please write an article on what happens and why when attempts are made to balance the budget. IMO, what Trump proposes is very inflationary. Also, I am concerned that most people don't realize money for Ukraine (and maybe Israel) winds up being spent in the American south at munitions factories. There is a reason that war is considered good for an economy.

When I see this, it terrifies me. The interest income channel as the primary driver of new money infusions to offset a lack of fiscal... this feels like Friedman lite as a return to mometarist thinking