Expectations play an important role in economics. When individuals feel confident about their economic prospects, they’re more likely to borrow and spend. And when companies expect strong and growing demand for their products, they’re more likely to hire additional workers or finance investments in new buildings, equipment, and technologies. As the famous British economist John Maynard Keynes explained nearly a century ago, expectations influence the state of our economy in all sorts of ways, especially when they change suddenly.

But when it comes to inflation, mainstream economists have taken the role of expectations to incredulous heights. According to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, inflation expectations—i.e. how people think prices will change in the future—are a key determinant of actual inflation. It’s sort of like the Kevin Costner baseball film Field of Dreams, except instead of believing “If you build it, they will come,” Powell believes “If you expect it, higher inflation will come.” And he’s not alone. Virtually every central banker talks about the importance of keeping the public’s inflation expectations “well-anchored” in order to prevent actual inflation from getting out of control.

I’m working on a book about inflation, and one of the chapters looks at how this hazy concept came to play such a dominant role in the making of monetary policy.

According to the Fed, one of the reasons—perhaps the main reason—inflation has trended back down after hitting a 40-yr high in the summer of 2022 is that inflation expectations never became “unanchored.” We’re told that it’s the independence of the Federal Reserve that allows it to retain “credibility” with investors and the public at large such that there is broad faith in the Fed’s commitment to restoring price stability. With that psychological outlook in place, actual prices drift down in line with expectations of inflation cooling. Inflation expectations lead and realized inflation follows.

One problem with all of this is that we can’t actually observe inflation expectations. We can try to divine them, using market measures like breakevens or we can look at economists’ forecasts or we can ask businesses and consumers to tell us where they think inflation is headed.

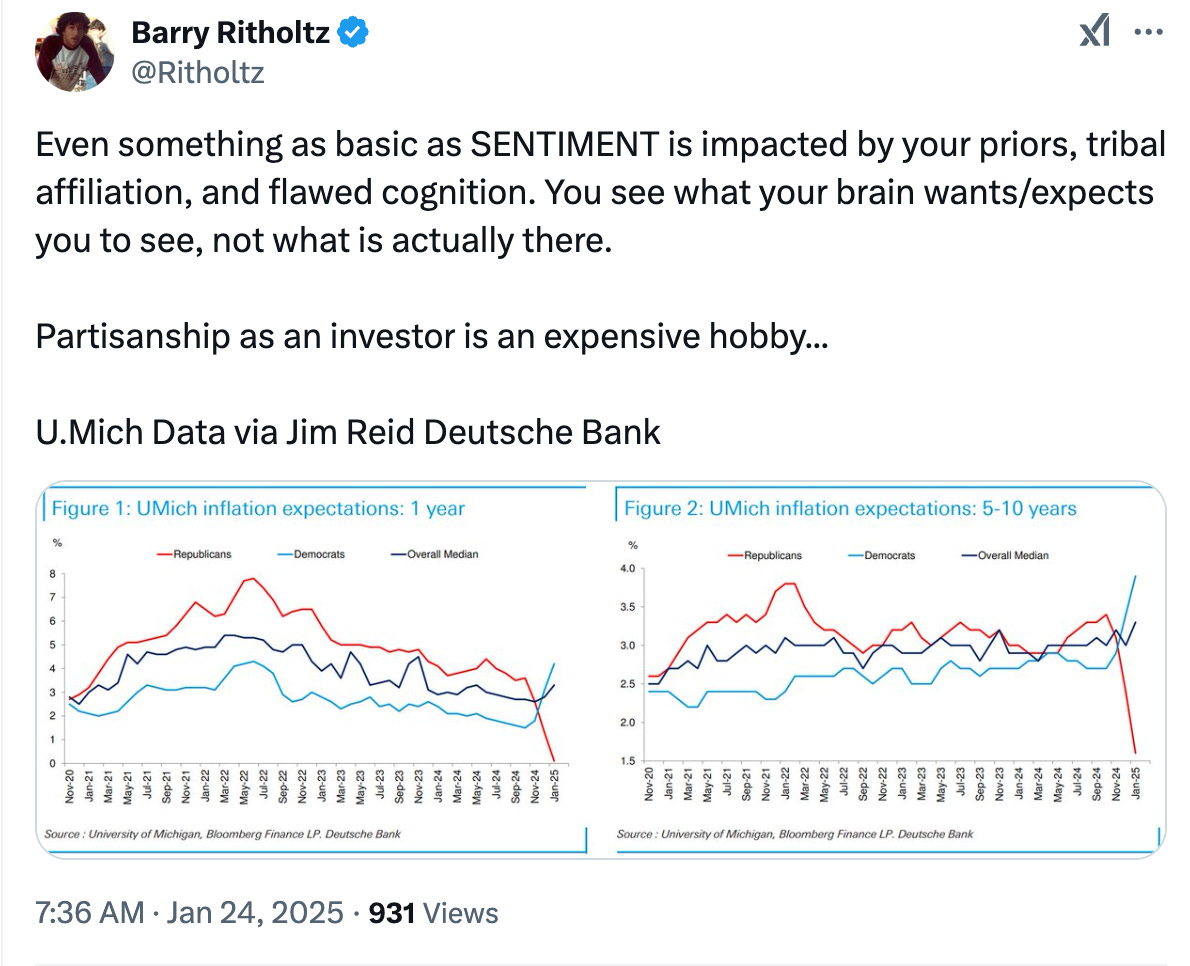

The University of Michigan conducts one of those surveys each month, and they’re scheduled to release the final numbers for January later today. It’s a closely watched survey of consumer sentiment that asks everyday Americans about their financial situation, where they think gas prices are head, whether they think it’s a good time to sell a home or buy a car, what they think of business conditions overall, and how they think prices in general will change over the next 12 months or over the next 5-10 years. Here’s what people’s inflation expectations look like when you sort them by political affiliation. Republicans basically think inflation is going to disappear altogether this year (and to be incredibly low over the next 5-10 years), while Democrats think it’s poised to surge higher.

But the partisan taint isn’t the only problem with surveys like these.

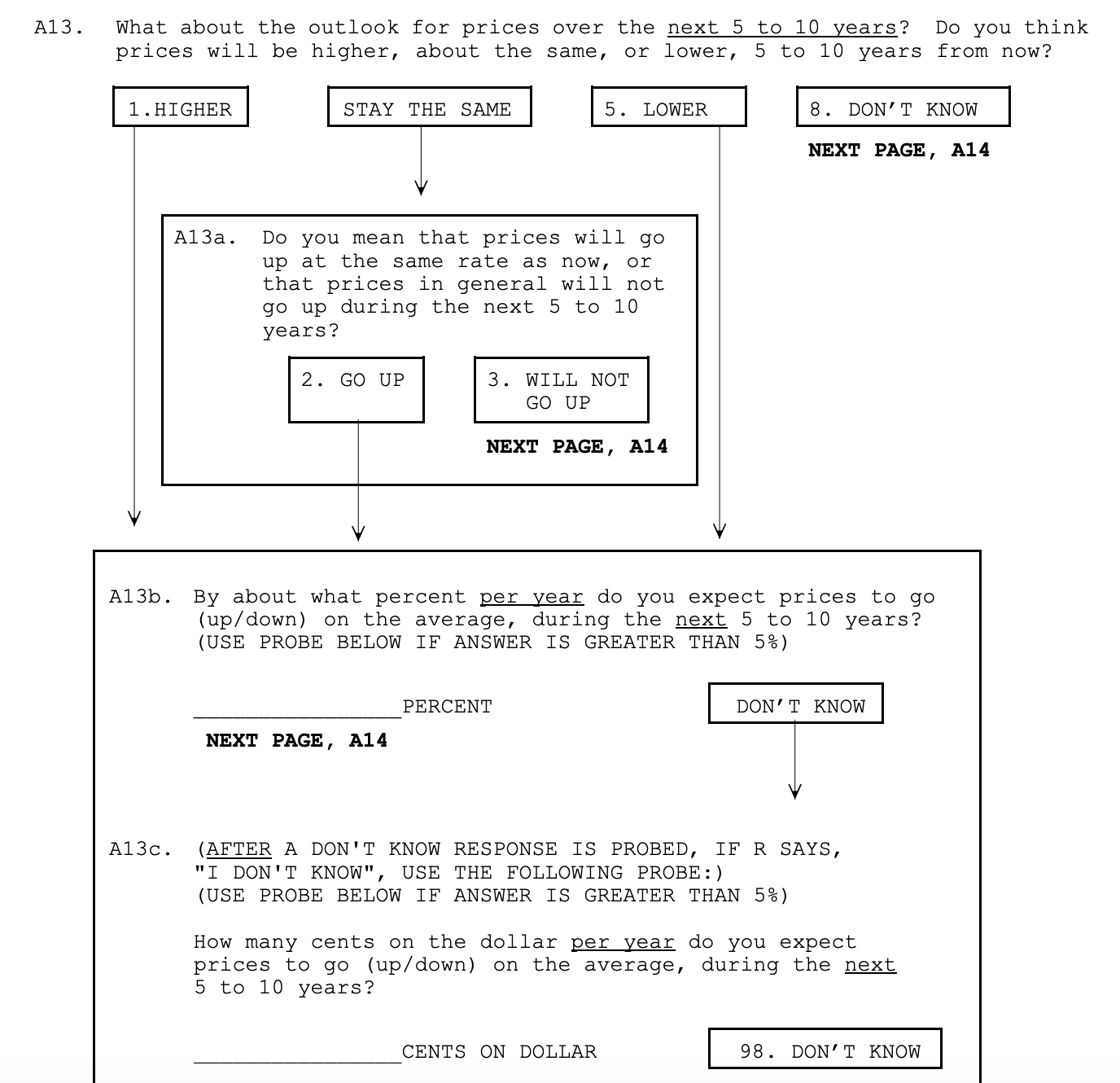

Former Fed economist Claudia Sahm did work with the Michigan survey, and she has listened to the tapes from the interviews. Here’s the questionnaire that’s used to survey everyday Americans. Below is the question that asks people how much they expect prices to rise, on average, over the next 5-10 years.

Claudia said, “My jaw hit the floor when I was listening to the inflation expectation questions.” She was stunned by how quickly most people would answer the questions and how many struggled with the concept of a percentage change. Claudia knows how much the Michigan survey means to the Fed, so “the fact that a lot of people really aren’t supplying answers that reflect any kind of actual understanding” came as a big surprise. She raised concerns about putting too much faith in “elegant theories” that rely on things—like inflation expectations—that are “really hard to measure” in practice.

Moreover, Claudia (like Keynes) acknowledges that people are mostly backward-looking. Partisanship aside, their expectations about the future tend to reflect what they’re experiencing already. She mentioned Richard Curtin’s book, which argues that people are gathering information from around them, not reading the latest inflation report, Fed speeches, etc. While central bankers desperately want to believe otherwise, consumers aren’t really telling us whether they find the Fed’s willingness and ability to reduce inflation “credible.” With the surveys now tainted by Red Team vs Blue Team, one wonders whether they’re telling us much at all.

“It would be foolish, in forming our expectations, to attach great weight to matters which are very uncertain. It is reasonable, therefore, to be guided to a considerable degree by the facts about which we feel somewhat confident, even though they may be less decisively relevant to the issue than other facts about which our knowledge is vague and scanty. For this reason the facts of the existing situation enter, in a sense disproportionately, into the formation of our long-term expectations; our usual practice being to take the existing situation and to project it into the future, modified only to the extent that we have more or less definite reasons for expecting a change.” ~J.M. Keynes

https://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/A-Framework-for-the-Analysis-of-the-Price-Level-and-Inflation.pdf

Nice overview of consumer survey measures! This paper (https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2021062pap.pdf) by a Federal Board economist offered a complementary perspective.