A couple of days ago, I wrote to my friend Dan Alpert to get his thoughts on a popular line of argument that’s been nagging at me for a while. Dan is Managing Partner at Westwood Capital, and someone I frequently correspond with about macro and financial markets. Dan thinks a lot about energy and oil.

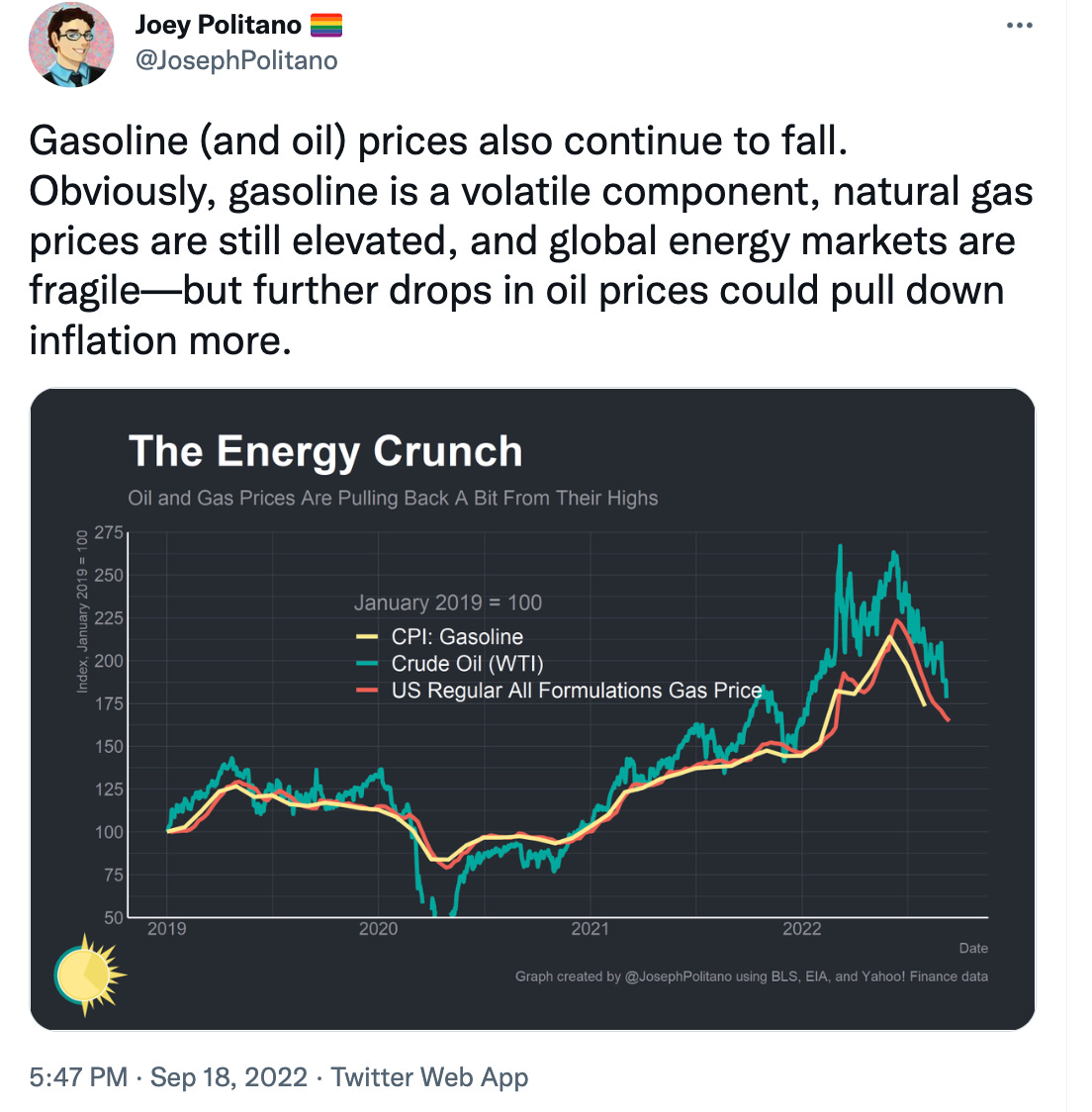

Here’s the popular line of argument: (1) We’d be doing a lot better on inflation if Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine; (2) Energy feeds into the cost of everything; (3) Food price inflation became a bigger deal when oil/energy prices shot up; (4) As energy prices come down, food prices will too. We haven’t seen it yet, but it’s inevitable because food is ~70% energy.

It’s a contested view, and I was struck by the apparent decoupling of food and energy prices in the 1970s. Click here or below to enlarge the chart.

Still, it makes sense to think that as energy prices fall, so should the prices of a broader range of consumer goods and services. But will they? I guess they could.

What Does Dan Alpert Think?

(In His Words)

This is the second time in 15 years that conventional thinking about oil has gotten things very wrong. The error has been compounded by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which actually came rather late in an oil price shock that was already well underway.

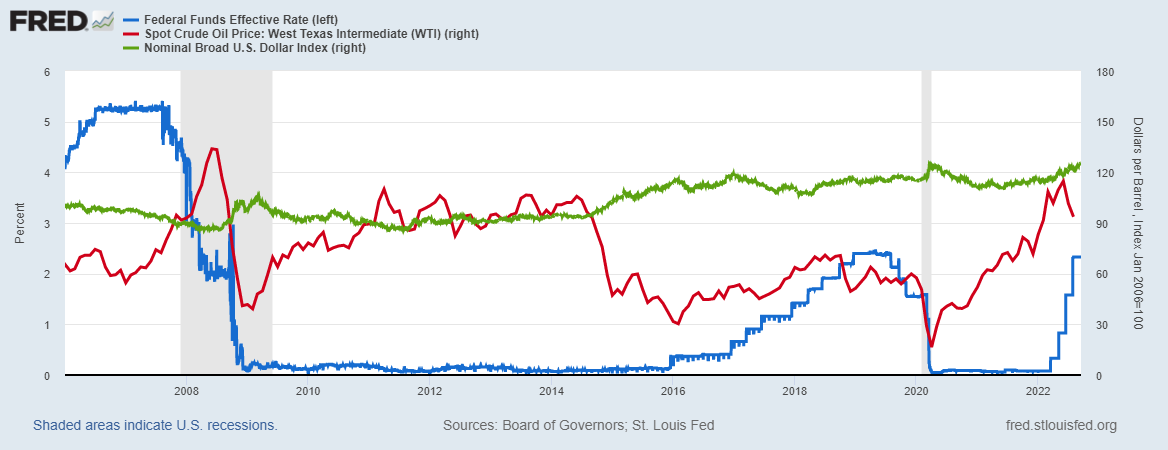

Oil shocks, and energy shocks more broadly, are conventionally attributed to supply constraints (either real or artificial) or demand surges (chiefly during periods of rapid expansion, either globally or regionally). But since late 2007 the financialization of oil has led to the use of the commodity in hedging and speculation strategies not directly related to the commodity itself, but to using the dollar denominated commodity to hedge U.S. inflation and the dollar itself (Bouchouev). Accordingly, during periods in which traders fear that the Fed will be forced into highly accommodative policy (especially in the most recent round in which such policy was accompanied by unprecedented fiscal stimulus and unique, albeit temporary, supply constraints related to the pandemic) they have increasingly tended express their concern regarding the prospect for inflation resulting in dollar devaluation by going long oil futures.

As it happens, that concern has proven to be misplaced, as illustrated in the graph above. Nevertheless, the upward pressure on oil prices resulting from these market actions has materially impacted general inflation, given the importance of energy as an economic input across many sectors. Although supply constraints and non-energy-related shipping costs had a material impact on food prices, petroleum is a major cost related to its fertilization, processing and transportation. Higher oil prices clearly have a knock-on effect on pricing across other goods and services sectors as well. And they are political quite volatile as consumers feel the effects of higher oil prices and food prices almost immediately.

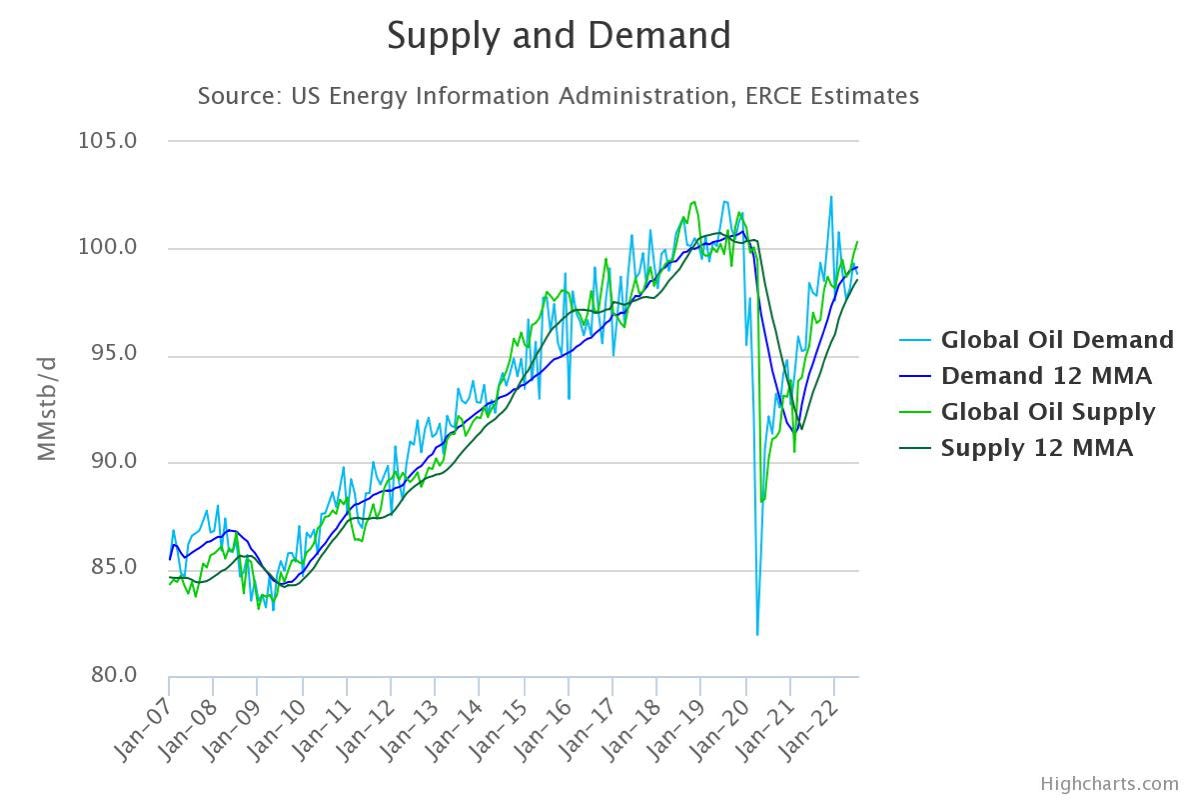

While the invasion of Ukraine and the problems with Russian oil supply caused an additional spike over the course of the past six months, that has been completely ameliorated – with oil having returned to a price level at or below that at the time of the Russian incursion. As with the period of 2007-2008, during the pandemic era when it became clear that the central bank would be forced to resort to extraordinarily accommodative policy (ZIRP, QE, etc.) we saw the oddity of oil prices moving higher during a period of inarguable economic weakness. This occurred even in the middle of the largest negative demand shock ever recorded, during the pandemic lockdown period, when the use of oil in transportation came to a near halt around the world - as illustrated in the above graph.

While global oil supply grossly exceeded demand from 2015 – 2018 (as a result of the fracking boom) and prices for oil ratcheted down considerably, by and large oil supply has gown with the global economy over the medium and long term. Today, demand for oil is materially below its pre-pandemic level, and while the disruptions associated with the Ukraine situation have required substantial redirection of the market for Russian oil, this has transpired in relatively short order and the Ukraine-related market spike has rolled over. Oil is a commodity with a longer-term decreasing demand trajectory, especially as alternative energy sources have grown more rapidly than older forecasts had expected. Finally, it just doesn’t make common sense, beyond the argument posited above, that – as illustrated in the first graph above – the price of petroleum has risen during global slumps.

I remain, therefore, very concerned about the Fed taking price signals from oil, energy in general, and the sectors that are heavily dependent on petroleum. While, admittedly posing a political hot potato issue, an understanding of the market and patience are warranted. Because while traders who have bet on oil made out well for a while, the commodity is now down 30% from its recent peak. And if I am right about the motivation of many in the oil futures market over the past 15 years, the price level today is not accurately reflective of underlying supply and demand for the commodity, and it therefore has further to fall over the coming year as earlier trades continue to unwind in the face of the strong dollar, supply is redirected, and demand further weakens.

With fiscal contraction playing out as it has, pandemic-related excess savings now rapidly exiting household balance sheets, the strong dollar, and supply chains and shipping costs nearly fully recovered, demand was certain to weaken from the boom period of Q2 2021 through Q2 2022, even without the massive Fed tightening we have already seen and are about to see more of this week.

To the extent the Fed has been motivated to tighten even in part as a result of the viscous feedback loop emanating from the rush into oil derivatives as a hedge against dollar devaluation and inflation, it has gone horribly off course into in an ocean of sludge that will unnecessarily gum up both commerce and employment in the U.S.

Thanks to Dan for writing such a thoughtful response to my provocation. You can find more of Dan’s writings here and follow him on Twitter here.

Thank you so much for sharing that illuminating analysis.Financialization strikes again!

My question is, why would speculators feel the fed raising interest rates and/or enacting accommodative policies would lead to higher inflation when the general Neoclassical view is these policies are to bring down inflation?

Regardless that the strength of the dollar and oil prices are showing not to correlate since the '70s