Magical Monetary Thinking at the Fed Killed SVB

By L. Randall Wray and Stephanie Kelton

Today’s post is a joint effort, written with my friend and former teacher/colleague, Randy Wray. Randy was a student of Hyman Minsky (and author of many books, including Why Minsky Matters.) We were trading e-mails about the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) over the weekend, and I suggested that we team up and write something for readers of The Lens. So here it is.

Before we turn to the story about how the Federal Reserve helped to blow up Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), let’s take a step back. It really is just another case of history repeating itself.

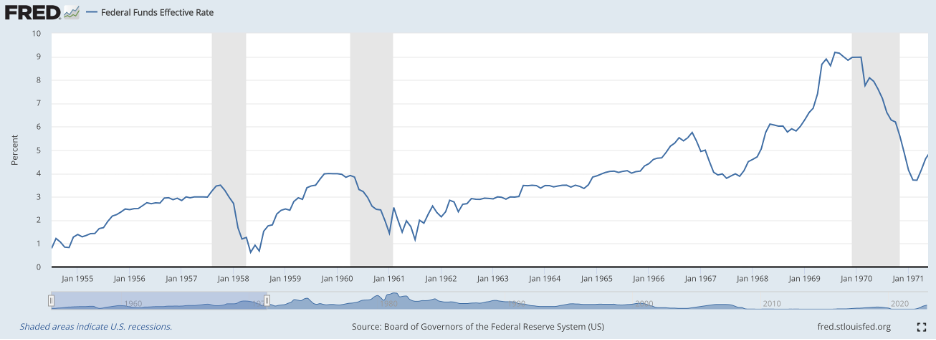

In the early postwar era, Keynesian ideas dominated policymaking. Fiscal policy—what Congress and the Treasury do—was front and center, focusing mostly on managing aggregate demand. While monetary policy had been freed from wartime constraints by the Treasury Accord of 1951, in practice the Federal Reserve played a mostly supportive role. Keynesians doubted that spending was sufficiently interest-sensitive to warrant assigning an important role to the Fed in demand management. In practice, the Fed kept the fed funds rate between 1 and 3% for most of the decade, but it raised rates to about 3.5% and then 4% as the economy went into double-dip recessions between 1958 and 1960.

By the mid 1960s, the Fed had taken rates above 5.5 percent, triggering the so-called credit crunch of 1966. It was the first financial crisis of the postwar period and one that required the first important postwar intervention by the Federal Reserve.

As Minsky described it:

By the end of August, the disorganization in the municipals market, rumors about the solvency and liquidity of savings institutions, and the frantic position-making efforts by money-market banks generated what can be characterized as a controlled panic. The situation clearly called for Federal Reserve action.

The Fed was forced to intervene as a lender-of-last resort to rescue the municipal bond market, which in effect validated the very practices that had stretched market liquidity. As a result of Fed intervention, confidence was restored, and the economy continued to expand. Before long, new financial practices would emerge and be validated, leverage ratios increased, memories of the “big one” (Great Depression) faded, and markets came to expect that big government and the Fed would come to the rescue as needed.

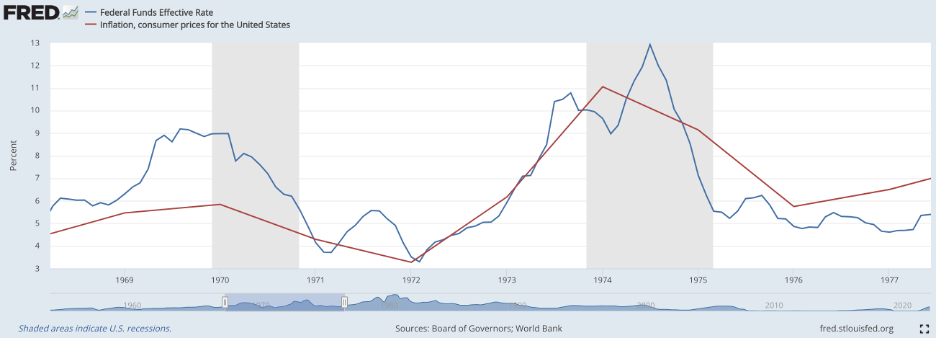

After the brief U-turn (Dec. 1966-July 1967) to ease the credit crunch, the Fed embarked on an aggressive rate hiking campaign that added 500-basis points of tightening between August 1967 and August 1969. It was a policy error that triggered another financial crisis, this time in the commercial paper market. The rate hikes led to a default (and then bankruptcy) by Penn Central railroad.

In December 1969, the economy entered a recession. Although inflation briefly retreated, it returned and then accelerated following the first oil price shock in 1973. With inflation moving higher, the Fed again hiked aggressively, taking the fed funds rate up by 850-basis points (July 1972-July 1974). Franklin National Bank failed in October, 1974—the biggest bank failure up to that time. And the economy crashed into the deepest postwar recession up to that period, ushering in the economy’s first stagflation.

As Minsky wrote in Stabilizing an Unstable Economy:

During 1974-75 more banks failed, and more assets were affected than in any other period since WWII. Moreover, the Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) industry, with some $20 billion in assets, experienced a severe run that led to many bankruptcies…

In addition, 1975 was marked by New York city’s financial crisis, the failure of W.T. Grant and company, the need for Consolidated Edison to sell assets to New York state in order to meet payment commitments, and the walking bankruptcy of Pan Am.

Keynesianism fell out of favor largely because it offered no cure for the malaise: the inflation should be treated with fiscal austerity while the unemployment called for a dose of fiscal stimulus.

The Beginning of Magical Thinking

As inflation picked up at the end of the 1970s, the Fed embraced a new view: Monetarism. Fiscal policy would focus on deficit reduction, while the central bank would target the growth rate of the money supply. Monetarists argued that the Phillips Curve trade-off was illusory. There was a “natural rate of unemployment,” and the central bank could bring down inflation without pain by reducing the rate of growth of the money supply.

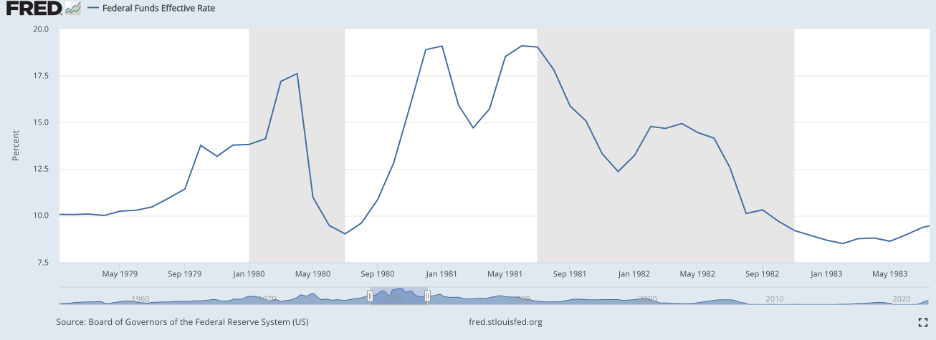

In 1979, a new sheriff came to town—Long Tall Paul Volcker. Interest rates were raised to 17% in May 1980 and to 19% by January 1981. And once again we experienced a financial crisis—one that spilled over into the rest of the world—along with a deep (double-dip) recession.

Minsky observed:

In 1982, a virtual epidemic of savings banks failed, and in midyear a spectacular bank failure—that of Penn Square in Oklahoma City—led to large losses at some of the citadels of American banking…. Then, in mid-1982 the Mexican peso collapsed, and default on multi-billion-dollar debts by a spate of Latin American countries seemed imminent.

Two years later, in May 1984, Continental Illinois Bank failed after a run on deposits. It was the biggest bank failure up to that point.

The most severe financial crisis since the Great Depression wiped out half the thrifts in the United States. And the knock-on effects from the rate hikes hit developing country debt, putting all the big banks that were holding that debt underwater by the end of the decade. But unlike the “tough love” shown to the S&Ls, the big banks were thrown various lifelines—lower interest rates, “extend and pretend” (banking supervisors didn’t look to closely at their books, hoping they wouldn’t crater), and safe government debt that allowed the big banks to recover.

Part of the reason for hesitancy to resolve insolvent banks was the understanding that the FDIC could not possibly cover losses on the deposits of technically insolvent big banks—the FSLIC (insurer for the S&Ls) had already gone bankrupt—coupled with the fact that Congress was in no mood for a “bail-out.”

Volcker’s grand monetarist experiment—letting go of interest rates and targeting the money supply to try to bring down inflation—forever changed the banking industry. The Jimmy Stewart savings & loan sector was allowed to recess into a distant memory of Christmas past. Banks started treating borrowers like one-night stands and loans like toxic waste, something to bundle up and quickly offload onto pension funds and other investors. Underwriting became passé. No need for regulations, either, because securities will be rated by professionals. Bank regulation and supervision took a long vacation. The age of securitization had arrived.

In 1987, Minsky wrote, “That which can be securitized will be securitized”:

Securitization reflects a change in the weight of market and bank funding capabilities: market funding capabilities have increased relative to the funding abilities of banks and depository financial intermediaries. It is in part a lagged response to monetarism. The fighting of inflation by constraining monetary growth opened opportunities for nonbanking financing techniques. The monetarist way of fighting inflation, which preceded the 1979 “practical monetarism” of [then–Federal Reserve Chairman Paul] Volcker, puts banks at a competitive disadvantage in terms of the short-term growth of their ability to fund assets…. The interest rates of the monetarist experiment destroyed the funding capabilities of the thrift “industry” in the United States by undermining the value of mortgages and thus impairing their net worth. The ability of the thrifts to create mortgages was unimpaired even as their ability to fund holdings was greatly impaired…. Although modern securitization may have begun with the thrifts, it has now expanded well beyond the thrifts and mortgage loans.

For policymakers, however the Volcker fiasco exposed a problem. Central banks can’t control the money supply (despite the carnage, the Fed never hit its money targets), and money supply growth isn’t related to inflation (money grew rapidly as inflation finally began to drop). What, then, should they target?

Enter more magical thinking as Greenspan took the reins in 1987. Greenspan embraced the view that inflation is driven by expected inflation, not by observable economic phenomena. Let’s target inflation expectations, which can be manipulated to control actual inflation! But we need some signal to communicate the Fed’s intentions. The Fed henceforth would openly announce the fed funds rate (believe it or not, the target was kept top secret until 1994). And the Fed would use the fed funds rate to indicate its intentions.

Sure, we know that spending isn’t very sensitive to interest rates, but expectations are, and that’s what matters. A rate hike will magically prevent inflation by creating the expectation that there will be no inflation. Believing that the Fed will prevent inflation will prevent inflation! As Peter Pan put it: “All the world is made of faith, and trust, and pixie dust.”

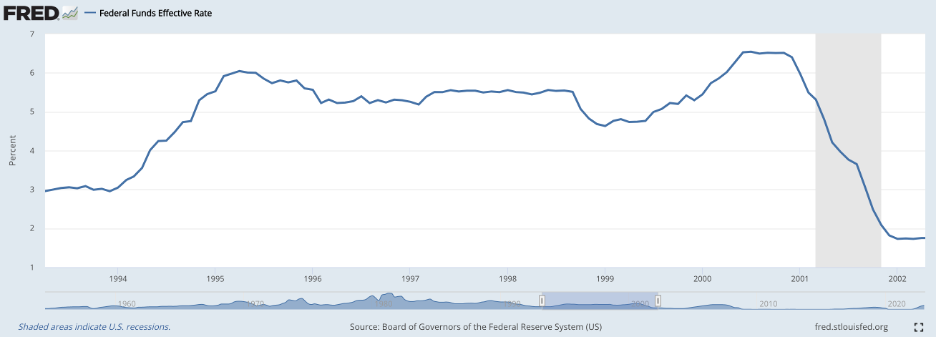

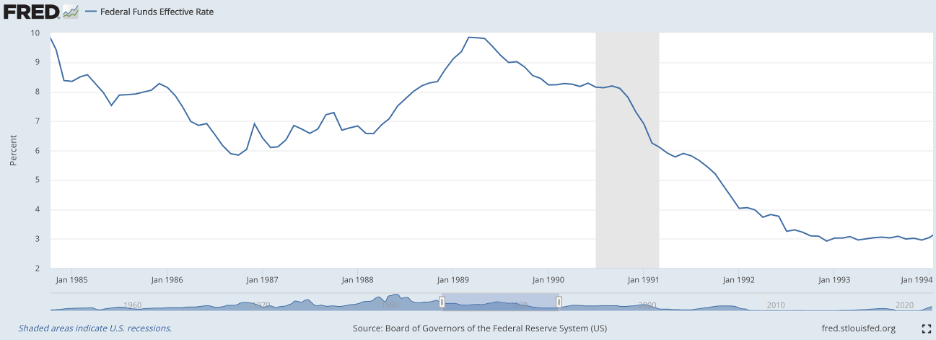

After Greenspan’s 1987 fiasco (the biggest stock market crash ever as rates were quickly pushed up from about 6% to nearly 7.5%), the Fed learned that a long series of small hikes is the best way to communicate intentions. Markets can gradually adjust to changed interest rate environments. Policy would change slowly—once headed in one direction, the Fed would continue to move in that direction for many months.

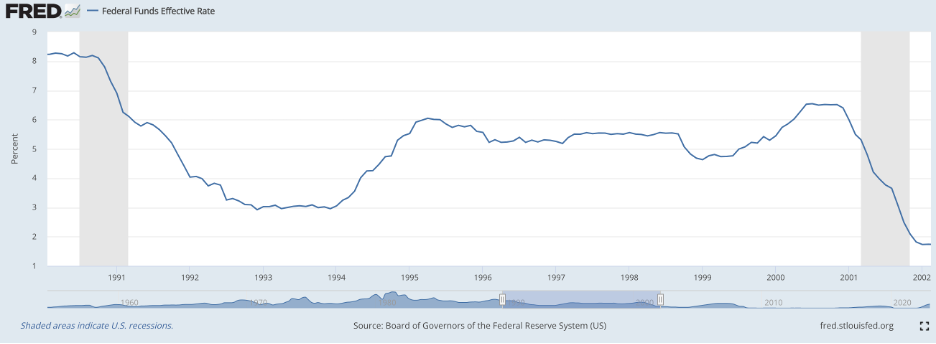

So the Fed continued to push rates up until it got the first Bush recession (1990/91)—followed by the first jobless recovery ever. A housing and tech stock boom finally restored reasonable growth in the mid-1990s during Clinton’s second term. Greenspan briefly fretted about irrational exuberance, but the Fed showed restraint, waiting until July 1999 to restart rate hikes.

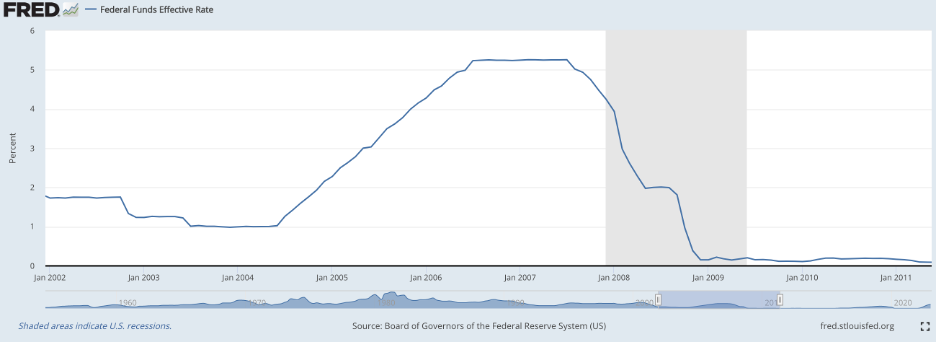

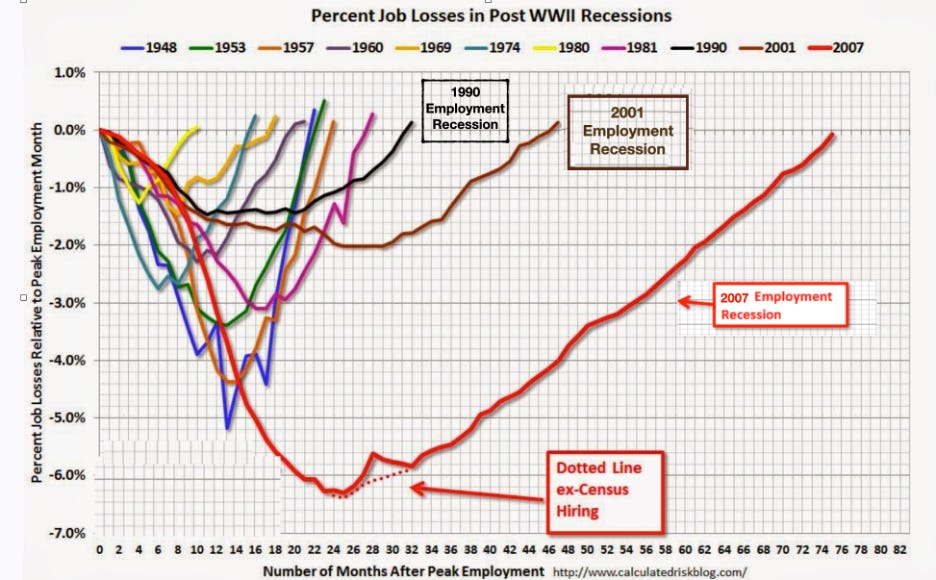

Before long, the dot.com bubble burst, and the economy was in recession (2001). Another jobless recovery ensued. Continuing a familiar pattern, new financial bubbles emerged—this time in commodities, housing and equities—helping the economy pick up steam.

In 2004, the Fed began a series of rate hikes that eventually culminated in the Global Financial Crisis. Washington Mutual failed in September 2008—the biggest bank failure up to that point. (Are you beginning to see a pattern?)

The rate hikes rippled through the financial system, driving mortgages underwater and pushing the economy into the most protracted economic downturn since the Great Depression. It took roughly seven years to claw back the jobs that were lost in the Great Recession. It was the ugliest “recovery” of all time.

Income inequality soared. And for the better part of a decade, the Federal Reserve waged battle against an inflation rate that was considered too low. The whole world watched as the Fed (and other central banks) attempted to raise expectations of inflation to bring actual inflation up to the 2% target. But neither zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) nor trillions of dollars of Quantitative Easing (QE) succeeded in restoring inflation to the Fed’s target.

Fed policy was trumped by expectations that had converged to the new reality. There was no inflationary pressure and no matter what the Fed did it could not get markets on board with its magical thinking.

Gradually, markets adapted to persistently low interest rates. In this new environment, leverage made sense. Holding long term assets made sense again. Financial markets bubbled. People got rich. Regulations were relaxed. The Trump administration exempted medium-sized banks like SVB from stricter rules. Banking supervisors went to sleep.

And then came a global pandemic.

After a bout of outright deflation in 2020, inflation picked up. But expectations remained stubbornly low. Clearly, expectations were not driving inflation, even as headline inflation rose well above 2 percent. Markets accepted Chairman Powell’s view that it was a transitory annoyance.

One year ago, the FOMC still expected interest rates to be in the 2% range for 2023 with inflation in the 2-3% range. Holding long maturity treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities still seemed safe. Why waste money hedging interest rate risk? The Fed wasn’t even bothering to stress-test bank portfolios for losses due to rising interest rates.

But inflation didn’t go away. Financial markets were signaling that inflation expectations remained, as they say, “well anchored,” but actual inflation wasn’t responding in kind. Eventually, the Fed decided it was time to return to the old playbook: quickly raise rates to show that the Fed is serious about bringing down inflation. However, financial markets were highly leveraged and portfolios were built on a perceived pact that the Fed would not destroy equity by over tightening.

But that raised a problem: banks that loaded up on safe government bonds and mortgage-backed securities had to either move them into the hold to maturity (HTM) category, or recognize losses due to largely non-hedged positions in longer term assets that could not be unloaded. Short sellers were able to pick out the banks with vulnerabilities and then start rumors that led to runs on uninsured deposits.

In the past week, we’ve had the second (SVB) and third (Signature) biggest bank failures up to this point. First Republic bank is being rescued by a consortium of 11 banks. Credit Suisse is a basket case. New bank failure records may be waiting in the wings.

Quick and decisive action by the Fed and FDIC can always avert calamity, but they failed to do so in the case of SVB. To prevent systemic crisis, FDIC insurance must be expanded to all bank deposits regardless of size. We need to move—quickly—to a system of FDIC insured banks, not FDIC insured depositors. Unfortunately, we may find that insurance will have to be provided outside the commercial banking system—to deposit-like liabilities of shadow banks (as we did for the money market mutual funds in the GFC).

It could get ugly. It will be a “bail-out”, no matter what the President says. We hope he sticks to his promise that shareholders and management will not be bailed-out. We hope that he claws-back bonuses and investigates the lax supervisors at the Fed. There’s growing evidence that Chairman Powell and others at the top of the regulatory food chain are at least partly responsible for the lack of oversight that allowed banks like SVB to take on risk. Perhaps some early retirements and resignations are in order.

So what is to be done?

We see two routes for long-term solutions:

Continue to embrace the free market. Reduce government-provided backstops. Continue to rely on monetary policy for aggregate demand management: raise rates to fight inflation, and then lower them to ease the damage of recession. Allow the bank failures that rate hikes inevitably generate. Learn to live with periodic financial crises. And expect a great depression every generation—which was the norm before the New Deal with its regulation of financial institutions and tremendous increase of the size of government.

Stabilize interest rates—stop using them for demand management and instead focus on financial stability. Regulate and supervise financial institutions. Retain backstops like deposit insurance and lender of last resort when necessary to stop crises from spreading. And restore a proper role for fiscal policy in managing aggregate demand.

I don't know enough about the financial sector to follow these arguments. My impression is that interest rate hikes serve two purposes which are dear to the heart of the corporate feudal class - creating unemployment and job insecurity among the masses, and increasing economic inequality.

This is solid advice but let’s also focus on creating high paying job training programs that will help with green infrastructure. Working on a public private partnership to create jobs in emerging technology areas with philanthropic involvement. Stay tuned for developments!