How to Cut $2 Trillion in Federal Spending Without Breaking a Sweat

As James Galbraith put it years ago, "It's the interest rate, stupid."

Last week, president-elect Donald Trump announced that he was tapping Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy to lead a new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to root out wasteful spending and overhaul federal agencies. While Trump didn’t commit to any particular dollar figure, Elon Musk pledged to cut “at least $2 trillion” from the federal budget. Almost immediately, liberal pundits began to sweat, declaring it all-but-impossible except by making draconian cuts that would inflict enormous pain on vulnerable Americans.

Writing for The American Prospect, Tim Iwayemi said, “The only way to make the cuts he’s talking about would be to gore Medicare and Social Security.” Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute concurred, warning, “To eliminate a third of government, you would have to dramatically eliminate full functions of the federal government. You would have to dramatically scale back programs like Social Security, Medicare, and defense and veterans.”

According to New York Times columnists Madeline Ngo and David Fahrenthold, it all comes down to math. They write (my emphasis):

Here’s the math, based on the 2023 budget: About a third of federal spending went to Medicare and Social Security, programs that aid older Americans. Mr. Trump has said explicitly that he will not cut those. Another 13 percent of the budget went to national defense. Based on his track record, Mr. Trump seems unlikely to make major cuts there, either. He massively boosted military spending in his first term, and has promised to “strengthen and modernize” the military in his second.

Another 10 percent of federal spending went to pay interest on the government’s existing debts. Mr. Musk has already cited that as an area of wasteful spending, recirculating an X post from his America PAC that identified interest payments as something the commission could “fix.” But it would be a risky place to pursue any cuts. The government already committed to making these payments, when it first borrowed the money. If the U.S. suddenly stopped paying them, the result could be a default that creates higher interest rates for average Americans and a potential recession.

That leaves about 40 percent of the budget. Cabinet agencies. Veterans’ benefits. Medicaid, which provides health care for the poor and disabled. Cutting $2 trillion from this sector alone would require huge cutbacks in services that Americans rely on. In the past, both Mr. Trump and Republicans in Congress have called for cuts — even large ones — to some of these programs. But they’ve shown no appetite for chopping them on the scale Mr. Musk has promised. Even the Department of Education, a top target for conservatives this year, supports school districts across the country and has allies on both sides in Congress.

In what follows, I want to take up the argument that interest expense is a “risky place to pursue cuts.”

Interest is the Obvious Place to Cut

Earlier today, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy laid out their overarching goals in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. They are threefold: identifying regulations that President Trump could eliminate by executive action; firing an untold (but substantial) number of federal employees; and reducing the amount of money the federal government spends. “Unlike government commissions or advisory committees, we won’t just write reports or cut ribbons. We’ll cut costs.”

They continued, “Critics claim that we can’t meaningfully close the federal deficit without taking aim at entitlement programs like Medicare and Medicaid, which require Congress to shrink. But this deflects attention from the sheer magnitude of waste, fraud and abuse that…DOGE aims to address by identifying pinpoint executive actions that would result in immediate savings…”

I think we can all agree that rooting out fraud and abuse is categorically a good thing. I thoroughly enjoyed this recent Odd Lots episode, which is all about how the new Department of Government Efficiency could help the federal government identify and curtail more fraudulent and abusive activity within an array of government programs. (Oddly absent was any discussion of fraud and abuse in the Pentagon budget, but I digress…)

But getting rid of “waste” is going to be much thornier. To borrow a metaphor, waste is in the eye of the beholder. At $6.75 trillion, the federal budget is big, and there are thousands of programs, subsidies, and other expenditures that might appear wasteful and unnecessary to the DOGE commission but which members of Congress, including many republicans, will consider beneficial or even vital to their communities.

So what kind of “waste” will Musk & Co. be looking to cut?

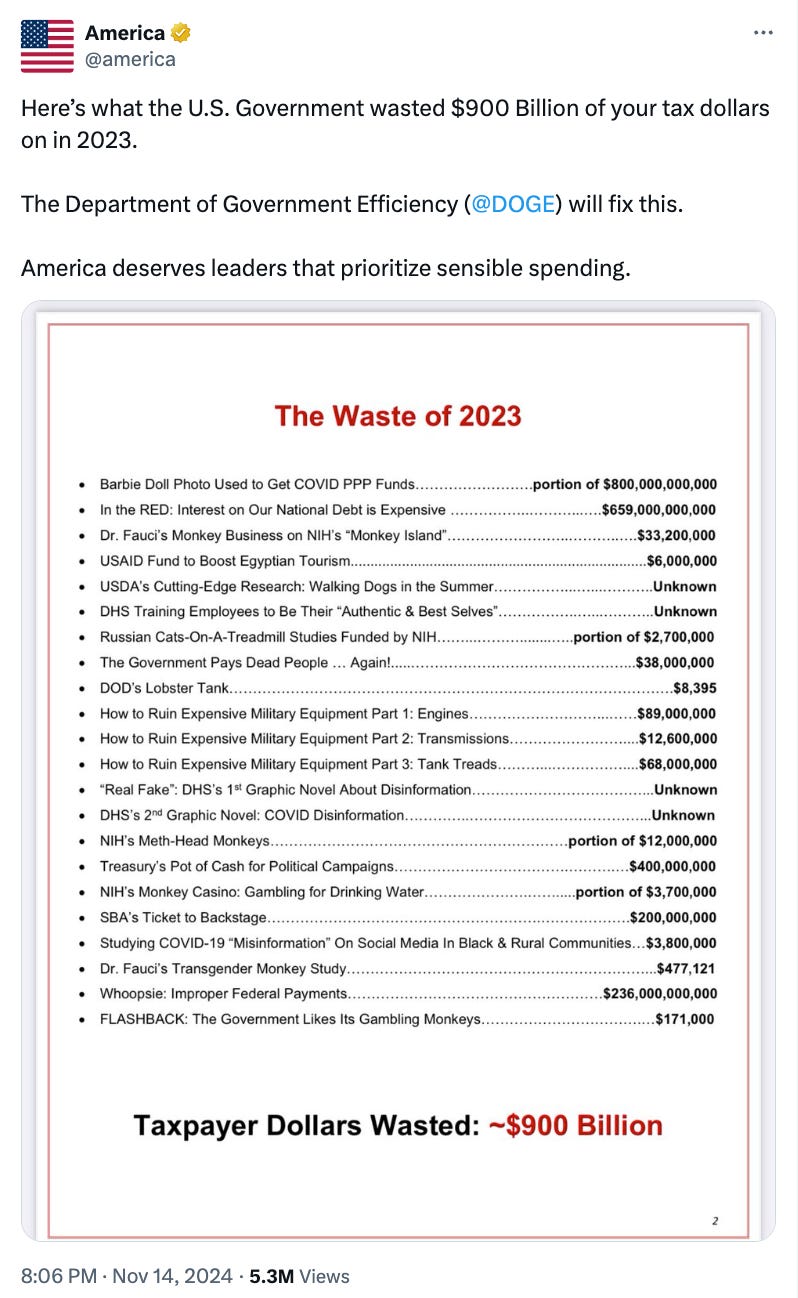

We got a preview last week, when a PAC founded by Elon Musk gave us an early look at some of the expenditures they consider wasteful. The biggest—by far—are the interest payments the federal government makes to holders of U.S. government securities—Treasury bills, notes, and bonds.

The list of “wasteful” expenditures drew scorn from across the political spectrum. The most negative reactions stemmed from the fact that interest expense was seen as a wasteful form of spending that could be cut.

That’s what led the New York Times columnists (quoted above) to complain that it would be a “risky place to pursue any cuts” because the government “already committed to making these payments” so it could be catastrophic if it “suddenly stopped paying them.” It evoked similar outrage from Washington Post columnist Heather Long, who called it a “farce” and suggested that there’s no easy way for the federal government to avoid paying hundreds of billions (or even trillions) in interest each year.

Conservatives, like Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute, also scoffed at the notion.

But here’s the thing.

There’s a difference between eliminating a third of government (as Brian Reidl suggested to The New York Times) and eliminating $2 trillion in spending. There’s also the issue of timing. Perhaps I missed it, but I haven’t seen Donald Trump, Elon Musk, or any republican member of Congress pledging to slash $2 trillion from a single year’s budget. If the goal is to reduce federal spending by $2 trillion or more—over some reasonably short period of time—that can be done fairly easily and without eliminating government agencies or cutting essential programs like Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid. And interest expenditure is exactly the right place to find those savings.

There’s also a difference between reducing interest payments and stopping payments as they come due. While Musk and Ramaswamy raise the possibility of violating the 1974 Impoundment Control Act in their new op-ed, there is no reason for President Trump to defy Congress in order to bring interest expenditure sharply down. He just needs Congress to take appropriate action to curb these expenditures over time.

As MMT scholars (Fullwiler, Mosler/Fullwiler, Wray, Kelton, etc.) have long reminded us, issuing bonds is a policy choice, and the interest rate that is paid on any securities the U.S. Treasury chooses to issue is also a policy choice. And there is growing recognition outside of the MMT community that the yield curve is a policy choice.

If you agree with Warren Mosler that interest payments are an income subsidy that overwhelmingly benefits “people who already have money,” making them a kind of “basic income for the rich,” then you might find it relatively easy to classify interest as a “wasteful” form of spending. If we continue down the path we’re on, the government will pay out tens of trillions of dollars to financial institutions and wealthy investors over the coming decade. That’s a large—and highly regressive—form of fiscal stimulus that Mosler thinks could help explain why inflation might be getting “sticky” or even poised to reaccelerate.

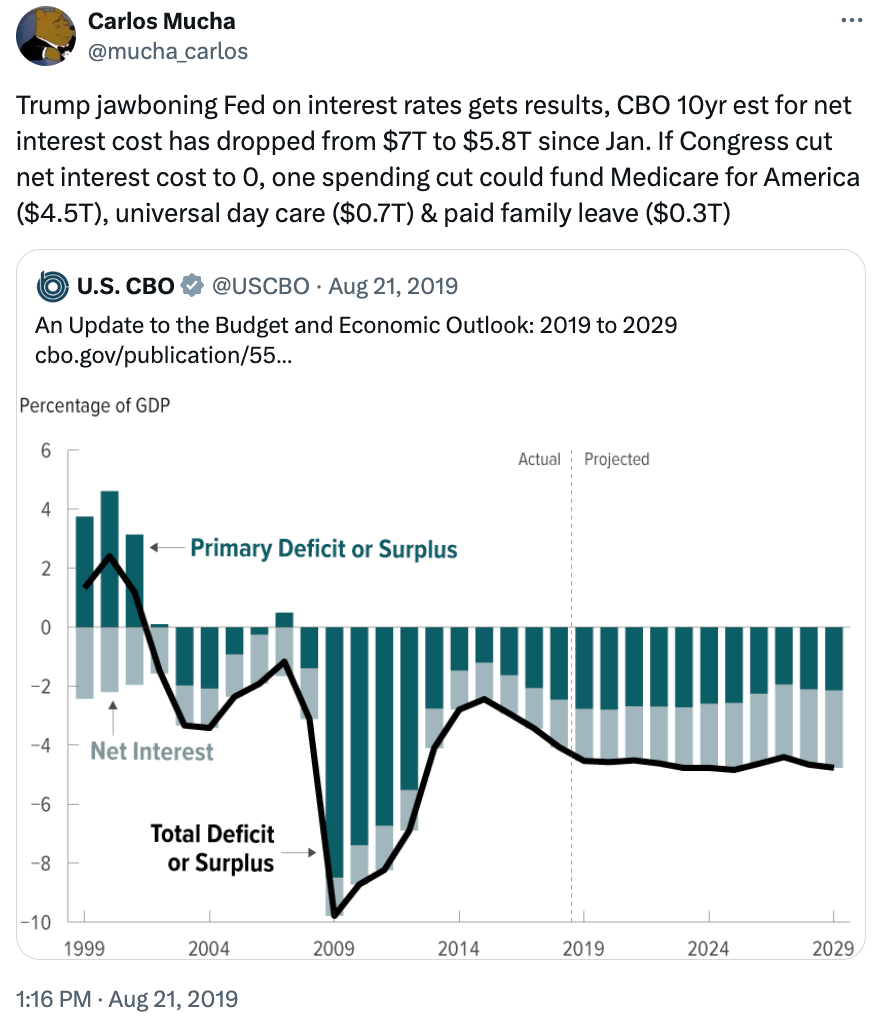

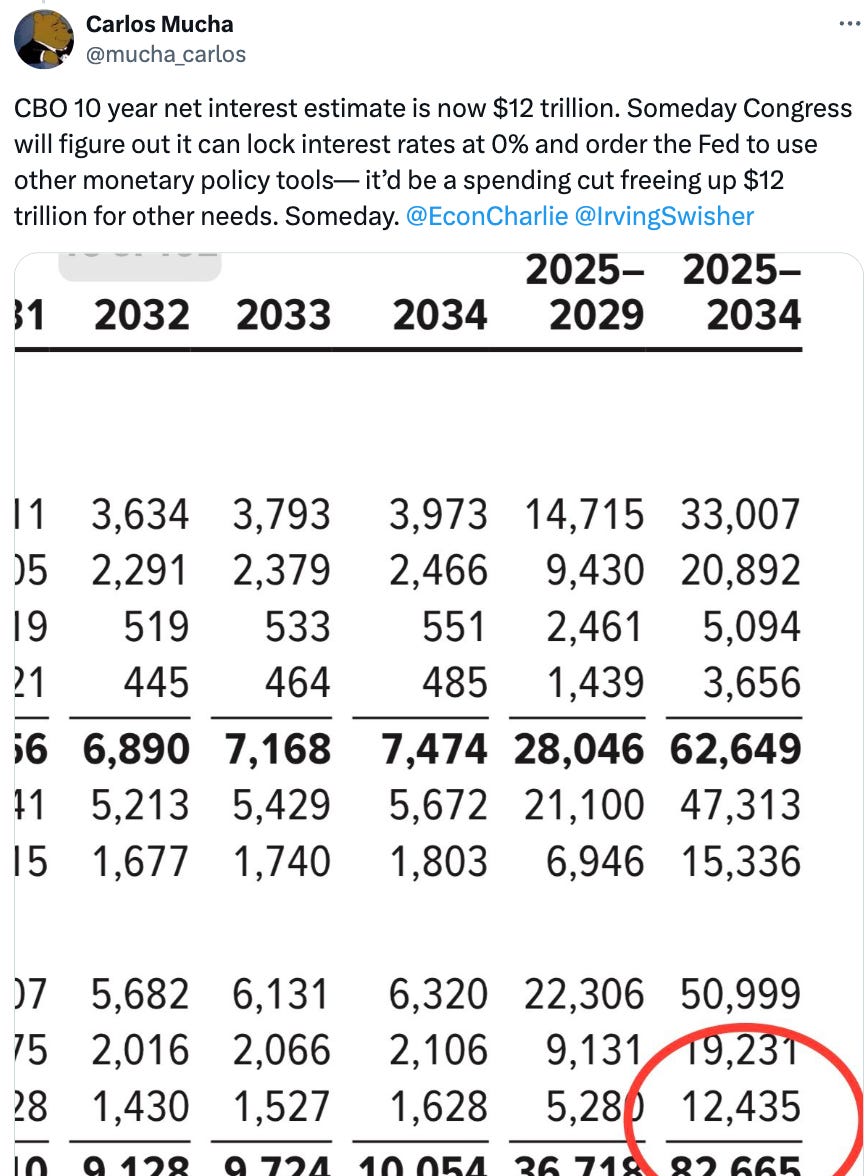

If the Federal Reserve were to cut rates sharply—either on its own or in response to political pressure, some of that fiscal largesse would disappear. And it doesn’t take all that long to for huge savings to materialize.

Just look what happened the last time Trump was president.

Now imagine what would happen if, instead of the president jawboning the Fed, the 119th Congress decided to exercise greater control over this part of the federal budget. To do that, it could instruct the Federal Reserve to permanently bring the overnight interest rate down to ~zero percent and to rely on other tools to influence the broader economy. To ensure that interest expense falls toward zero over time, Congress could instruct the U.S. Treasury to stop issuing anything with duration beyond a 3-mo T-bill. Voilà! It wouldn’t just save $2 trillion, it would save tens of trillions of dollars over time.

In Closing

To be sure, this would trigger outrage and pearl-clutching from central bankers as well as many lawmakers, academics, pundits, and journalists. But consider where we are. Donald Trump has put the world’s richest man in charge of an effort to slash and burn whatever he deems intrusive, cumbersome, or irrelevant. He’s looking to carve at least $2 trillion from somewhere. The cuts can debilitate federal agencies—Musk indicated that he is looking to eliminate as many as 300 federal agencies—and programs like SNAP, Medicaid, Head Start, WIC, LIHEAP, SSI, etc. that tens of millions of Americans rely on to get by. Or we can try to steer republicans in a direction where they will do minimal harm to the class of voters who handed Donald Trump his electoral victory—those making less than $100,000 a year.

Liberals appear almost resigned to defeat. It’s just “math,” and there’s no easy way to cut $2 trillion without inflicting enormous pain on vulnerable Americans. Except there is. It’s the interest rate, stupid.

This would be great, if they followed your prescription to the letter. And we get the added benefit of near eliminating what is effectively a fiscal stimulus program for people with money, regressively distributed to people the more money they have.

I think the bigger problem is, in practice, another Trump presidency will come with another round of deep cuts to social programs (ones that most Americans aren't familiar with). In my occupation, I get to deal with a lot of nonprofits, which mostly do the critical work on the ground to support the most disadvantaged individuals and communities. They have all been through Trump 1.0, and they know what the outlook is for their organizations after the elections. A lot of them with major projects in the pipeline are already planning for delays and scaling back of their projects, due to the now uncertainty around federal funding that they were relying on in their projections.

Its funny, DOGE to me is a grift for guys like Elon Musk who along with his rich buddies will get their generous tax breaks while they'll look to implement austerity for the working poor to so call "pay for" those breaks. Like this article mentions, the more simplistic way of cutting 2 trillion would be to reduce those regressive int payments that benefit the rich. Cutting rates to zero would be huge and could eventually free up dollars to benefit the working class.