This morning, I went (back) down the rabbit hole on the sterling crisis that supposedly drove the British government into the arms of the IMF in 1976. I’m not a historian of British economic history, but other MMT economists (and some non-economist MMT scholars) have written at length about the period. And I mean at length. (Here’s a 7-part series, and here’s a piece with more than a dozen links to other posts that cover the period leading up to 1976).

All of that writing was done by Australian MMT economist Bill Mitchell, and it offers a deep dive into the political and economic history that culminated in the now-infamous 1976 IMF loan. I don’t have the bandwidth to write up a comprehensive summary, but you can follow the links if you have the appetite for a thoroughgoing take from an MMT voice.

Why is this relevant now?

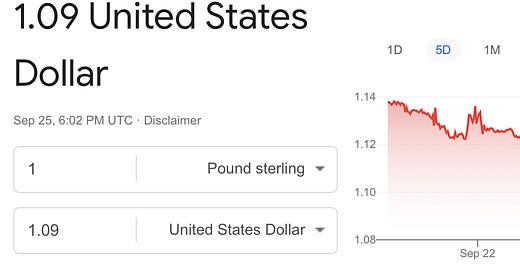

Well, the release of the Truss/Kwarteng “mini budget” last Friday triggered a sharp decline in the exchange rate that’s got some people asking whether the British government might be sleepwalking into a kind of 1976-style currency crisis. Along with the drop in the pound, interest rates on gilt-edged bonds moved sharply higher on the day. To some observers, it looked all too familiar. Could the British government once again “run out of money” and find itself needing to turn to the IMF for a “bailout”?

Back in the mid-1970s, the leader of the Labour Party, Prime Minister James Callaghan, was wrestling with many challenges that look familiar in the contemporary moment. High inflation fueled by a surge in energy prices, a widening current account deficit, a sharp depreciation of the British pound, and rising anxiety about the economic situation.

What happened that drove Callaghan and his chancellor, Denis Healey, to seek a loan from the IMF? Was it really necessary? Could it happen now?

For quick-and-dirty answers to some of these questions, check out this post from Bill. Scroll down to the section with the heading, A Summation. As Bill has explained elsewhere, Denis Healey went to the IMF under the pretext that the British government was running out of money.

It’s a complicated history, but Bill argues that Healey became infatuated with monetarism and persuaded Callaghan to impose austerity. If you read the speech Callaghan delivered at the annual Labour Party Conference in Blackpool in 1976, you’ll find it laden with direct and indirect references to TINA—there is no other way.

Together, Callaghan and Healey persuaded the Labour Party and the Trade Unions that the government was running out of money. That it had no choice but to borrow £3.9 billion from the IMF in order to avoid risking a crash in bond markets that would leave the government unable to fund itself.

In Bill’s telling, austerity was the Labour government’s objective, not its punishment. The IMF loan simply allowed the government to pursue unpopular budget adjustments—spending cuts and tax hikes—under the cover of IMF loan conditionality.

Another very good voice on all of this is British MMTer Neil Wilson. Wilson is an engineer by training, though he has experience working in banking. Here’s Neil, commenting on one of Bill’s posts back in 2016.

I thought the IMF loan was put in place to help discharge the us dollar swap facility agreed in June 1976 with the US Secretary of State to the Treasury.

page 5 of the June 1976 cabinet minutes

So they signed the Brits up to a swap facility on the understanding they would go to the IMF to repay it.

Seems to be confirmed as drawn on page 6 here

So the UK was already up to its eyeballs in debt in a foreign currency before the IMF was even spoken to.

Unlike in 1976, the UK is not currently “up to its eyeballs” in debt denominated in a foreign currency. And the British government never needs to borrow the pound from the IMF (or anyone else). It is, after all, the issuer of the that sovereign currency. So it really comes down to the exchange rate—not “funding” per se— as Bill and Neil explain.

This is 100% correct. In a fiat currency system with no gold backing, the equilibrating mechanism is no longer interest rates per se, but the level of the free-floating currency relative to other currencies (esp the $). In such a situation, the relevance as far as the UK is concerned is the extent of foreign (i.e. non-sterling) borrowings on the debt. In the UK's case today, it is a non-factor. Virtually all of the borrowing is being done in sterling, so there is no question as to whether the UK government can continue to service the debt because, as the sole issuer of the pound, it can always service the debt. I also suspect that at some point, sterling becomes sufficiently low relative to other currencies, and that may well attract additional inflows from institutions/individuals, who view sterling based assets as "cheap".

That the UK government is highly unlikely to face a 1970s style currency crisis in which the IMF might have to be called in DOES NOT, however, vindicate the strategy adopted by the Truss Administration. The new policies announced last week by Kwasi Kwarteng offer the worst of all possible worlds: they do nothing to address the gaps in the supply chains that did so much to create the inflation in the first place. To the extent that this package delivers expansionary fiscal stimulus, it is directed to the wrong people. The benefits largely accrue to the cohort with the highest savings propensities, so it's terribly inefficient and will also likely exacerbate prevailing inequalities (and the UK is one of the most unequal economies in the G7, in fact it might be THE most unequal and this fiscal plan will make it worse). In fact, as the Shadow Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, noted the other day in the FT, "research by the IMF has shown that higher income inequality is associated with lower and more fragile growth. It is obvious why. Concentrating income among fewer people — those least likely to spend it and drive the economy forwards — undermines workers’ health and education, the crucial components of a productive workforce."

Likewise, as Stephanie pointed out in her previous piece, there is a substantial body of economic work illustrating that "trickle down economics" is fiscally inefficient in terms of delivering decent bang for the buck to foster greater economic growth. So to the extent that the tax cuts induce any kind of spending response, we'll get more demand that will likely go to the wrong areas (e.g. prime London property), as opposed to funds that will generate more equitable growth and prosperity.

Sadly, the British government remains very deliberately wedded to the myth that it needs to run to the nearest lender every time the stationery cupboard gets low on pencils. (The feudal aristocracy of the private economy would have it no other way.)